Greece crisis: profiling rich, scot-free yacht-owners

Published on

Translation by:

Cafebabel ENG (NS)The economic flavour of the Greek crisis tastes different for those on top - the shipowners, the yachting association bosses - than the diet prescribed for the masses. In Athens though, the latter rage against the state rather than the privileged classes. Lucky richies

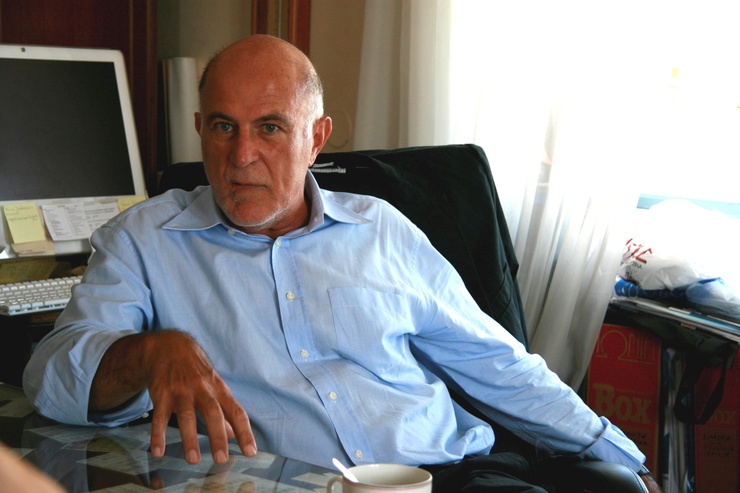

Judging by the decor of his office in the chic Athenian neighbourhood of Kifissia, the so-called 'Harry Potter of Greek maritime merchants' likes contemporary art almost as much as his self-portraits. At 27, Harry Vafias became the youngest CEO of a maritime association to be listed in New York's Nasdaq technology stock exchange. That was back in 2005. Today, Stealthgas hasn't seemed to have suffered the effects of the Greek crisis. 'There's been no direct impact,' comes the peremptory reply, as Vafias momentarily looks up from his three computer screens. 'It has an indirect effect. It plays on the psychology of employees who can't consume as much as before. Employees having less money affects business!'

Greek shipping magnates navigate troubled waters

'The only effect that the crisis had was on weakening the banks,' explains Harry Vafias; it's meant he can't borrow in Greece anymore. But what about these reports of the millions of euros in bank accounts that rich citizens and most listed Greek societies have transferred to Swiss, Cypriot and British banks? It's also had an impact on these weakened banks, surely. 'The government duped the Greeks,' he replies. 'Not us. We're like the Greeks from a legal standpoint.'

'The only effect that the crisis had was on weakening the banks,' explains Harry Vafias; it's meant he can't borrow in Greece anymore. But what about these reports of the millions of euros in bank accounts that rich citizens and most listed Greek societies have transferred to Swiss, Cypriot and British banks? It's also had an impact on these weakened banks, surely. 'The government duped the Greeks,' he replies. 'Not us. We're like the Greeks from a legal standpoint.'

Or beneath them, as Giorgos Glynos tells me from his plush loft high up on a hill in the popular district of Exarchia. The shipowners aren't bothered by the tax hike,' claims the Eliamep research centre economist, although VAT has just risen from 21% to 23%. 'That's the paradox of the Greek economy: rich shipowners, the most prosperous entrepeneurs in the country, find it easy to dodge the fiscal system. All they need to do is fly the flag of convenience.' This form of fiscal evasion is part and parcel of the international nature of the business, but is also down to the benevolence of Greek politicians, according to Giorgos Glynos. 'Successive governments have always tried to entice shipowners into registering their ships here rather than abroad by offering them an advantageous tax rate.' In his blog, French journalist Jean Quatremer, who is the Brussels correspondent for the daily Liberation, confirmed this after meeting the Greek finance minister: 'The income generated from the shipowners in Greece is only taxes if they want it to be taxed.'

'Greece isn't a business country'

Does this mean the rich shipowners haven't experienced the crisis? 'Of course, the business has been touched by the crisis,' says George A. Vernicos, president of Vernicos Yachts, a national leader in yacht sales and chartering. 'Fortunately the business of selling boats, which is our main activity, has been on the rise over the last decade and isn't really at risk.' 'Mr Yachting', as the media clippings hung in his office nickname him, doesn't accuse the government though. 'Everything is difficult here. Greece isn't a business country.' Harry Vafias' words echo this statement. 'Two problems choke Greece: there are too many civil servants and the Greeks are incapable of paying their taxes.' For these two giants in the Greek economy, the state is the guilty one.

Strange. Back in the loud arena of the average Athenian taxpayer, the views are the same. 'The Greeks aren't against the rich people, they're against the government,' insists an employee at a jewellery shop in the city centre. The owner of the boutique is none other than the mother of Alexis Grigoropoulos, a fifteen-year-old student who was murdered by policemen on 6 December 2008. Amidst the police blunder of 2008, the student protests that ensued and current protests against the Papandreou government's austerity measures, a similar rage at politicians and civil servants has gripped Greek society. From rich ship owners and young 'anarchists' to shopkeepers, everyone has a bone to pick with the state.

Public enemy number one in Greece: the state, not the rich

For the French, it 'seems normal that the economic and political elite make a fuss over each other,' as the Swiss daily, the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, wrote in reaction to the Eric Woerth-Liliane Bettencourt affair (the French tax scandal of June 2010). That's why it is hard to not hear a single Greek taking offence at the inequalities between the economic elite and the others. Only the political class are hauled over the coals. One woman, the wife of a rich plastic surgeon who lives in the plush neighbourhood of Kyfissia, explains that this is mainly because the state is in the 'hands of three families': the Papandreous, the Karamanlis and the Mitsotakis.

Are the shipowners adept at the subsidiary transmission of the business? 'Most young people here don't even know they exist,' whispers the daughter of the director Theo Angelopoulos, who we bump into at a bar in Exarchia. The revolutionary graffiti and anarchist propaganda splattering the walls of this trendy district are firmly directed at the state, despite their marxist, anti-capitalist vein. 'The Greek spirit has been very militant since the colonels junta (the 1965 – 1974 dictatorship - ed),' analyses Giorgos Glynos. 'But as there's never been a capitalist class to oppose, the state has become the enemy.' The state and its three reigning families. Meanwhile, the rich continue to smoothly evade taxes. 'The class enemy,' concludes the economist, 'is the state, and thus the public interest!'

Are the shipowners adept at the subsidiary transmission of the business? 'Most young people here don't even know they exist,' whispers the daughter of the director Theo Angelopoulos, who we bump into at a bar in Exarchia. The revolutionary graffiti and anarchist propaganda splattering the walls of this trendy district are firmly directed at the state, despite their marxist, anti-capitalist vein. 'The Greek spirit has been very militant since the colonels junta (the 1965 – 1974 dictatorship - ed),' analyses Giorgos Glynos. 'But as there's never been a capitalist class to oppose, the state has become the enemy.' The state and its three reigning families. Meanwhile, the rich continue to smoothly evade taxes. 'The class enemy,' concludes the economist, 'is the state, and thus the public interest!'

Thanks to Elina Makri and the cafebabel team in Athens. Read their blog 'frappebabel'

Images: main ©davesag/ Flickr; Harry Vafias courtesy of ©HV; Georges A. Vernicos and his marina ©Dana Cojbuc; graffiti ©Elina Makri

Translated from La crise grecque à bord d'un yacht