Gonçalo M. Tavares: 'I hate the idea that everything you do is new'

Published on

The Luanda-born epistemology professor at Lisbon University, 38, talks his award-winning novel 'Jerusalem', and why it took him so long to get published already

It’s verging on rain as Gonçalo M. Tavares steps into the hotel lobby from a late morning walk in Ljubljana. His gait and features are soft like his voice. The self-professed ‘city-dweller’ compares the Slovenian capital to the town of Aveiro in the north of Portugal, where he grew up before moving to Lisbon aged eighteen. His mind works fast and playfully. ‘I like small cities,’ his eyes laugh.

Choosing an identity

We are joined by Barbara Jursic, a translator of his books to Slovenian. As he jumps back and forth between English to Portuguese, Tavares talks about how Europe did not bring a lot for him as a reader and a writer – literary translations into Portuguese are still scarce - although it brings together many identities. ‘But in the shadow of this economic crisis, a wider identity than just a European identity is surfacing,’ he says. Tavares compares his own identity to that of a builder. His father, a construction worker, ‘often took me with him to work. The builders would dig a hole, make foundations and slowly build higher and higher. My favourite moment was when it was all finished and we would drive away, but the house remained. I came to like the idea of building things that acquire their own independence.’ His own love for books came from his father’s library. ‘Today I am here and somewhere someone is reading my books,’ he smiles. ‘They live lives of their own.’

is surfacing,’ he says. Tavares compares his own identity to that of a builder. His father, a construction worker, ‘often took me with him to work. The builders would dig a hole, make foundations and slowly build higher and higher. My favourite moment was when it was all finished and we would drive away, but the house remained. I came to like the idea of building things that acquire their own independence.’ His own love for books came from his father’s library. ‘Today I am here and somewhere someone is reading my books,’ he smiles. ‘They live lives of their own.’

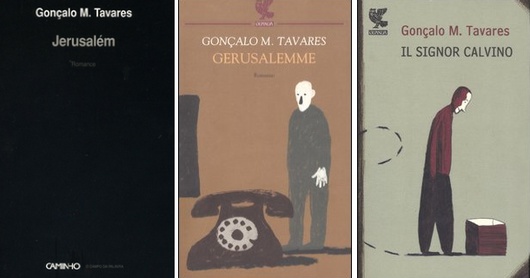

As a guest at the Fabula International Story Festival in the Slovenian capital, Tavares is presenting his novel Jerusalem (Círculo de Leitores 2004; Caminho 2005) and short story collection ‘Neighborhood’. Each one of the seven installments in the latter is dedicated to the likes of a Mr Brecht (O Senhor Brecht, 2003) or a Mr Walser (O Senhor Walser, 2006), authors in whose work Tavares found a ‘special sparkle of joy.’ The first female author, Ms Woolf, is also about to take up residence. While marked by the style or themes of a Henri or a Calvino, each story is wrapped up in Tavares' own world of small absurdities. ‘I never plan what I will write, characteristics just surface and I develop them.’ With this method, Tavares aims to create something personal in the background of literal theory and history. ‘I hate the idea that everything you do is new,’ he explains passionately, leaning across the table. ‘It is frivolous. Only someone who knows no history and has not read much finds everything new and original.’

Hate and frivolity

For years, Tavares ‘postponed’ publishing his writing, fearing it would be too confusing. It took him six years to publish another short story collection, Water, Dog, Horse, Head, in 2006, because he re-read and edited so much that they became new books. ‘Only after I had written like this and read even more, I felt I knew where I stood. I was ready to be received well or badly.’ He got lucky with his poetry collection Livro da dança (‘Book of the Dance’ Assírio & Alvim), in 2001. Today, his works inspire admiration and affection from the likes of Nobel prize winner Jose Saramago, who upon awarding him the Saramago prize for Jerusalem in 2005, claimed that ‘Gonçalo M. Tavares has no right to be writing so well at the age of 35! One feels like punching him!’

For years, Tavares ‘postponed’ publishing his writing, fearing it would be too confusing. It took him six years to publish another short story collection, Water, Dog, Horse, Head, in 2006, because he re-read and edited so much that they became new books. ‘Only after I had written like this and read even more, I felt I knew where I stood. I was ready to be received well or badly.’ He got lucky with his poetry collection Livro da dança (‘Book of the Dance’ Assírio & Alvim), in 2001. Today, his works inspire admiration and affection from the likes of Nobel prize winner Jose Saramago, who upon awarding him the Saramago prize for Jerusalem in 2005, claimed that ‘Gonçalo M. Tavares has no right to be writing so well at the age of 35! One feels like punching him!’

Jerusalem, a novel on violence, madness and pain, has been described as ‘one of the greatest works of western literature’ and won the Portugal Telecom award in 2007. It circles around a woman in a mental asylum. Tavares laughs as we discuss his fascination with ‘strange people’. Heroes are not only those who do great things - at the ending of Jerusalem, the heroine Mylia stands in front of the church doors and asks: ‘I killed a man. Will you allow me to enter?’ Like the ancient Greeks, Tavares believes in heroes who have a great thought at the moment they are faced with an unprecedented event. He despises symbolism. The hospital Georg Rosenberg that features in Jerusalem ‘can be connected,’ he says, with the Nazi ideologist Alfred Rosenberg, despite the fact that it wasn’t done intentionally so. ‘But maybe the name has something to do with the architecture - it is for readers to ask themselves these questions. I do not have an original answer and even if I had it, it would only be an obstacle.’

Open source Tavares

Today, his stories inspire installations, operas and plays, the most recent currently showing in Belem and Porto Alegre in Brazil. Tavares claims he attaches no sentimental ties to his work, and regards it in a modern, open-source way. ‘Amazing things were done. I tell artists to feel free if they find it necessary to move away from my texts. It is their work now. It matters in itself.’ Contemporary art inspires him in particular because it is ‘full of ideas. It is not the form that matters, but the questions and thoughts it invokes in people.’

As for whether he thinks books are still a hip form of expression, Tavares ponders a moment before sitting up confidently and answering. ‘The internet is not a problem if people pay for what they read. I prefer paper, though - to touch the book, have it in my hands, it feels good. In general, the idea of writing and words will never die. Books as a material thing, maybe. Homer did not write like I write today nor did he write books as we know them today. Yet, for centuries works of fiction have remained. People need them to know what happens in the world.’ And writing too is a need: ‘It must not be a way to correct mistakes or compensate for some traumatic experiences. You know that nothing can give you what writing can. The pleasure of building – houses, places.’