Gianluca Costantini: 'the main topic of the comic underground was sex - now it's politics'

Published on

Translation by:

Michelle Williams

Michelle Williams

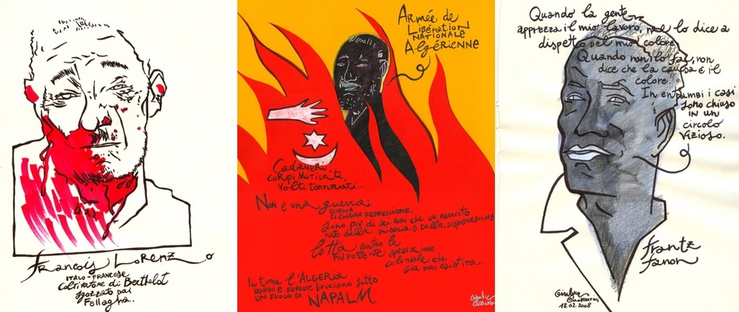

Gianluca Costantini, 37, is one of the focal points of the Italian and European comic world. He is also both an artist and an editorial director; with his Inguine Mah!gazine, created in collaboration with Electra Stamboulis, he is at the heart of all things 'underground comic'

Gianluca Costantini is in Ravenna. It's where his magazine is based, in the cellar of the library-cum-gallery of the Mirada Association, which he also manages. I accompany a comic friend Andrea Zoli, with whom I had previously interviewed Costantini for a fanpage distributed on leaflets. Termed PuntoGIF ('GIF files, aka 'Greatest Italian Failure!'), the leaflets came into being after the infatuation with cult seventies magazines like Métal Hurlant ('Hurling Metal', 1974), Cannibale (1977) and Frigidaire (1980), which all in turn stopped production.

I enter the library and exchange pleasantries with Costantini, following him to the spiral staircase leasing to the studio office. It is a small room with two desks, a couple of computers, a large quantity of sketches and designs thrown together, accumulated and reduced by peoples opinions to nothing. Our main intention is to understand what 'underground' is and whether it is the exclusive territory of dreamers and bustlers. Do you have to leave your own ideals behind you in order to live as a comic or to make a breakthrough in the genre?

Neither censure nor copyright

As an artist Costantini progressed in the comic world for the first time in 1993 when he published articles at a national level for his first magazine. He confesses to us that this was after 'having received a lot of rejection from editors.' In an attempt to make a headlong rush into the internet world he initially accompanied illustrations and 'decorative comedy' in a period of 'editorial crisis'. This project was in fact unique to the web and the 'perfect instrument of design', even when you consider that when the 'site changes, everything goes up in the air.' The web became the shop window which allowed Costantini to make his political comedy known on an international level. It was a type of diary with short, comic stories which via the web was transported to all corners of the world.

'Underground comedy isn't bought, is public and can be enjoyed'

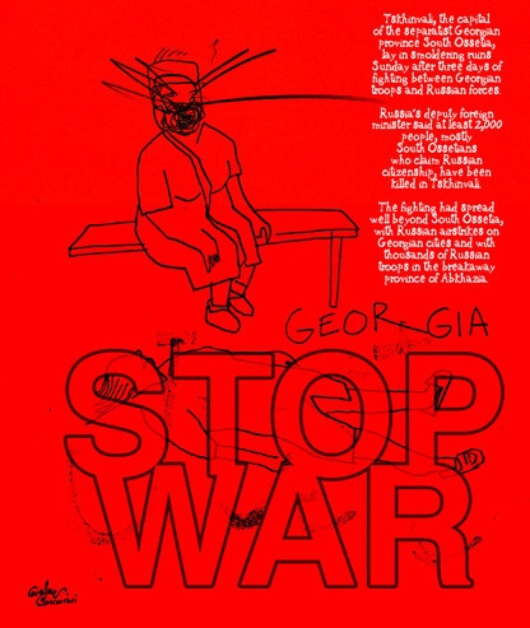

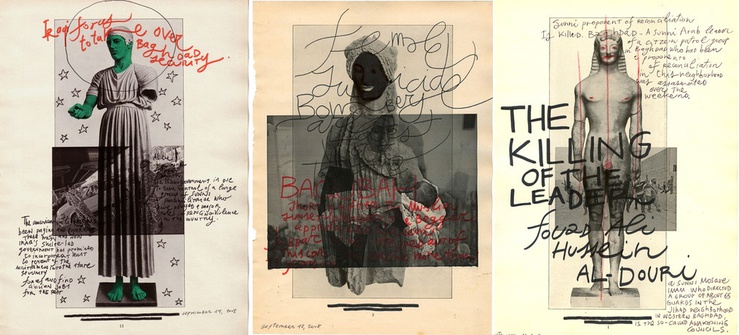

'After ten years of 'decorative' comedy which almost broke me as an artist, I completely changed direction and style,' he says. 'It is something which you don't usually do if you are intelligent. For me it was also a way to learn things after a long period when I was stuck in the studio designing and I knew very little of the world. These images remained for a long time despite the manifestos of the social centres in both Italy and abroad rejecting my work. I began to often use two-faced people for my illustrations because they gave a stronger value to my designs. This was underground comedy: it wasn't bought, it was public and could be enjoyed. It wasn't censored or copyrighted.'

From sex to politics

Is it radical change and the success that follows it which allows an artist to gain the necessary freedom to be properly experimental? This restless attitude is another distinctive trait of the underground movement. 'If you wish to succeed you must break the mould - do something different, absolutely different, that no one has ever done before. Continually change your style and you are made for life - the most interesting thing is using a different style each time. The approach is most important. You need designs - just like the painters of the fifteenth century. I design eight hours a day and have done ever since I was fifteen.'

Is it radical change and the success that follows it which allows an artist to gain the necessary freedom to be properly experimental? This restless attitude is another distinctive trait of the underground movement. 'If you wish to succeed you must break the mould - do something different, absolutely different, that no one has ever done before. Continually change your style and you are made for life - the most interesting thing is using a different style each time. The approach is most important. You need designs - just like the painters of the fifteenth century. I design eight hours a day and have done ever since I was fifteen.'

The underground doesn't just eliminate questions of style. It also treats themes like images and editorial lines. 'In the seventies, for example, the main topic of the underground was sex because it was something scandalous. Now the main topic is politics. The perfect example is World War 3 Illustrated in New York, in a comic magazine created by political activists, which uses people like Peter Kuper and design to discuss strong ideas and opinions,' explains Costantini. However it remains quite difficult to understand the confines of the underground and the artists who aren't in it for the usual motives (like the money) can be counted on one hand. Amongst these are the graphic artist Blu and the Swedish and American comic artists Max Anderson and Robert Crumb. The sad truth is that almost without exception, 'only those who work for 'popular' comedy succeed in living from this income.'

Costantini's activities aren't just exhausted in this environment. He uses other facilities to promote himself from perectly organised shows, meetings and debates to the Kamikaze festival, which he created with Electra Stamboulis. They brought authors of calibre like the Maltese-American Joe Sacco, French-Iranian Marjane Satrapi and Serbian Aleksander Zograf to Italy. These authors were brought to prominence with this festival as it travelled around Europe. It is also a way to move amongst the european comic underground scene. Speaking of the reality of some artists Costantini points out the former Yugoslavia. 'There are phenomenal artists there, yet no platform exists for them so they remain underground. They tell things how they are and perform how they see things. They are totally at peace and happy. In France however there are some of the biggest comic markets in the world and you can hear interesting things from all subjects.'

As for some names of European artists who we can 'unveil'? After a pause of several seconds we are given only one name - 'the spaniard Raul. He only wrote three comic books and now he doesn't do it anymore. Now he is an illustrator for a newspaper. He doesn't even have a website so you have to look for his books in Spanish.' The search is on.

Translated from Gianluca Costantini: «L’underground? Senza committente, con un pubblico, senza censure e copyright»