Getting to grips with Byzantium, Constantinople, Istanbul and Europe

Published on

Translation by:

victor escandell

victor escandell

The history of Anatolia is as old as the earth itself. The last ones to arrive (from Central Asia) were the Turks, who are heading slowly towards membership of the EU. However, didn’t its territory belong to the other ancient and almost forgotten European Union? We revise a strong heritage from books and the streets of Istanbul

Upon arriving in Istanbul you expect to see and hear noisy bazaars, mosques and rays of sun glistening over silky fabrics. You want to smoke shisha and listen to old stories told by old bearded men. But your first impression is quite different: here people are also in a rush to get to work, there are also massive shops, expensive cars and tens of thousands of visitors like yourself. So how can you trace the ottoman taste among the tourist queues? Or even better, how can you trace the European essence under the ottoman taste?

Sailors, politics and substance

The Hittites, Assyrians, Ancient Greeks and Romans left their footprint on Constantinople. It’s not that the Roman empire collapsed in the fifth century, but rather that it lost its western half. The other half was in good enough shape to last around the capital for another two thousand years. Constantinople was the richest and most populated city in the middle ages. It is the only one in the world (to date) that lies between two continents, Europe and Asia. Founded centuries ago by Greek sailors, the byzantine metropolis carried a nourished greco-roman tradition boosted by a young force, the orthodox christians.

‘It was a diplomacy that tried to avoid war,’ explains British historian Judith Herrin, professor at King’s College London and writer of Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire (2008), as she sums up the pillars of the so-called ’new Rome’. ‘It was an international, cosmopolitan and multicultural empire which was relatively tolerant towards other languages and religions. It had a highly educated elite that copied and commented on the old Greek works, preserving them to the modern world.’

Today, all that substance gathers dust in specialised books. Turkish pupils mainly study ottoman history which begins with the collapse of Constantinople in 1453 and which focuses on politics too. Restorers anonymously point out that the current moderate islamist government doesn’t pay attention to byzantine studies as a result of an old rivalry; for some centuries Byzantium blocked the muslim advance towards Europe.

Today, all that substance gathers dust in specialised books. Turkish pupils mainly study ottoman history which begins with the collapse of Constantinople in 1453 and which focuses on politics too. Restorers anonymously point out that the current moderate islamist government doesn’t pay attention to byzantine studies as a result of an old rivalry; for some centuries Byzantium blocked the muslim advance towards Europe.

Survivors of the past

What is left today from all this, aside from the impossible domes, the converted churches and the mosaics? Where do the little habits survive? An especially cold autumn shrouds Istanbul. People go around in thick jumpers and coats and they go more often to the Turkish baths to relax and eliminate toxins. That's where the direct legacy is. ‘Byzantine people had public baths for men and women which were used for altruist purposes like cleaning the leper,’ explains Judith Herrin. ‘The ottomans inherited plenty of things from byzantine people, especially charitable institutions such as orphanages or poor people’s houses, although not all of them survive in current Turkey.’

Once the bath is finished, you feel like having a piping hot tea and a proper meal. ‘The cuisine is another area of continuity,’ resumes Herrin. ‘We don’t know exactly the way byzantine people cooked, but it’s clear that they used plenty of olive oil, onions and vegetables, which still remains the base of Turkish cuisine.’ Cultural aspects like these spread all over Europe. In the west we owe them something as common as the fork. The Slavs were massively influenced by them and thus inherited more hallmarks such as the orthodox religion, the cyrillic alphabet used today by Russians, Bulgarians and Serbs, the habit of concentrating power in a fortress (Russian; ’kreml’) and the passion for political intrigues - out of 107 byzantine emperors only thirty-four died due to natural causes and six of them at war.

The tough western middle ages, with their feudal system and crusaders, have passed on the term ‘byzantine’ as a synonym for needless sophistication, cowardice and conspiracy for fear of unsheathing the swords. However, it’s just another echo of rivalry (or maybe jealousy). Constantinople was so important that everyone referred to it simply as ‘The City’ (‘eis tin poli’ in in ancient Greek), and people sought 'The City' out whenever someone was seeking a reputation, fortune or shelter.

Perhaps in five years time Turkey will join the European Union. Negotiations are long and thorny, the opposition (France and Germany) is strong, and also the scepticism. However many analysts think is inevitable. It seems that the European Union and Turkey will embrace like two drops of mercury in order to repeat a project that existed two thousand years ago with two new features: the rich islamic heritage and the circumstances. Now the neighbour wants to be annexed.

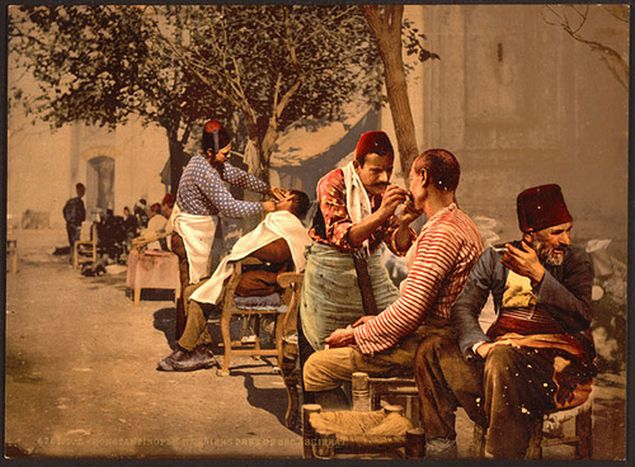

Images: main barber scene in Istanbul 1880-1900 - 'The City' stopped being known as Constantinople in 1930 (cc) yuecelnabi Nabi Yücel/ Flickr; Ayia Sofia: (cc) Christopher Chanc; Erdogan: (cc) World Economic Forum/ all via Flickr

Translated from "A la Ciudad": Pistas para encontrar a Europa en Estambul