German Russians: home in Berlin

Published on

Translation by:

The story of a community's unconventional journey: 'German Russians' return to Berlin and struggle to live in harmony in their adopted country

In the commercial centre of the city, there's a sign hanging horizontally which reads Eastgate in large letters, and which blocks the innumerable buildings that fill the landscape. On the streets, ' the language here' is heard everywhere: Russian. The 'Marzahn' district in Berlin has 103, 000 inhabitants; 28, 000 of whom only have a cloudy memory of Russia, kept in one corner of their minds. Most ''German Russians', the so-called 'Germans from Russia', have German nationality; they were expatriated long ago and now they have have inherited it.

Their history goes all the way back to the 1760's, when 'Catherine's invitation' meant that 30, 000 Germans were to be displaced 'to develop agricultural zones in southern Russia, notably in Ukraine, still under Russian rule. Catherine II of Russia wanted reputable German workers, to step in with the execution of colonisation,' says Frank Tétart, geopolitician, and director of the political research lab, LEPAC (Laboratory of Political and Cartographic Studies).

These Germans lived together, they benefited from several privileges, and also preserved their 'Germanity.' Lenin had given them their own nation state, 'the Union of Socialist Republics of the Volga Germans'; but with the Second World War, which brought opposition between USSR and Germany, their precarious situation blew up : the German population had to be then deported to Siberia, and the Republics of Asia Minor, today, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

These Germans lived together, they benefited from several privileges, and also preserved their 'Germanity.' Lenin had given them their own nation state, 'the Union of Socialist Republics of the Volga Germans'; but with the Second World War, which brought opposition between USSR and Germany, their precarious situation blew up : the German population had to be then deported to Siberia, and the Republics of Asia Minor, today, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Born before 1993?

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the population had reason to hope for more. Having inherited German nationality, they had the right to a second life in the country of their ancestors. Since 1990, they have been validating their status as 'Aussiedler' (resettlers). Because the right of blood still prevails in Germany, they have the benefit of a double nationality. Centuries after the departure of their ancestors, what are they looking for now, and why have they come to Berlin? Often, they have lost all their ties with Germany. Certainly, for some of them, this is a veritable return to their roots, motivated by the hope of a better life in an adopted home.

Eduard Walz, a grocer who lives in Lichtenberg, left the Ural Mountains in 1990 to move to Berlin. He took a chance : 'Having a double nationality enables us to leave, because in Russia, our prospects for the future were so limited.' Vassili Sagasdachny, a member of the Russian association Schalasch, is part of the second wave of re-patriots who came to Berlin during the last decade. Having lived humbly in Kazakhstan, he wanted 'to see how life was in Berlin.' Today, he wouldn't leave for anything in the world.

If German authorities were not considered vigilant in the nineties, they are now severe, as immigration laws have toughened. Administrative procedures is heavy and can sometimes last for years. From now on, anyone who wants to claim their rights, must have been born before 1993.

25% of repatriates speak German

The German Russians are therefore looking to rejoin their family members, in the regions where the state had created the first exclusively Russian communities. In Berlin, Marzahn is the largest 'colony' of the capital. Going backwards, and to 'support their integration,' the German state has imposed 'land ' quotas since 2002. Children go to school, young people study, adults work or look for a position. Integration is moving along, even if, in Berlin, there are few employment opportunities.

Eduard, after his education in furniture making, which was financed by an employment agency, quickly changed his specialised trade. 'It's impossible to earn a living as a furniture maker in Berlin. The labour is too heavy to pay,' he thinks. 'Here, I can't compete with the big distribution chains like Kaufland,' he explains.

Eduard, after his education in furniture making, which was financed by an employment agency, quickly changed his specialised trade. 'It's impossible to earn a living as a furniture maker in Berlin. The labour is too heavy to pay,' he thinks. 'Here, I can't compete with the big distribution chains like Kaufland,' he explains.

In order to find a job, it's conditional, sine qua non, to speak German. Frank Tétart estimates that if 70% of the first repatriates spoke German, of the most recent arrivals only one quarter of them are German speakers. 'Children have a better chance because they go to school and they learn German, even if it isn't being spoken in their homes,' Valentina Zapp, director of the project at Schalasch, explains. Every day she helps young people find their place in a school or in an apprenticeship, or writing letters of support. 'After one year of catching-up, they continue in the normal course. The German education system is too elitist. Berlin offers few prospects,' she says.

Borrowed identity

Anna Mamonov is 25 years old. She arrived in Germany with her mother when she was nine years old. For her, like all children, the question of her identity is still unresolved. 'I feel like I've been ripped from my childhood and my country.' Although Anna is integrated within her society, she thinks of herself as being primarily Russian. And for those who are born on German soil? For them, it's just the opposite: they hear Russian being spoken in their homes, they don't want to learn it because whether at school, or with their friends, they don't speak anything but German. The Valentina Association proposes the revival of the Russian language in young people.

Despite all the efforts, Germans keep in their minds an image of 'Asi' or welfare, when they think about the Russian population, who are often perceived as second rate citizens. This situation is one in which the Russian Germans suffer, Eduard explains: 'Financially, it's better here for them than in Russia. But in general, here, its not total freedom. We are still under pressure. There are way too many laws. For me, my homeland is still Russia.'

Crazy 'Russendisko' parties

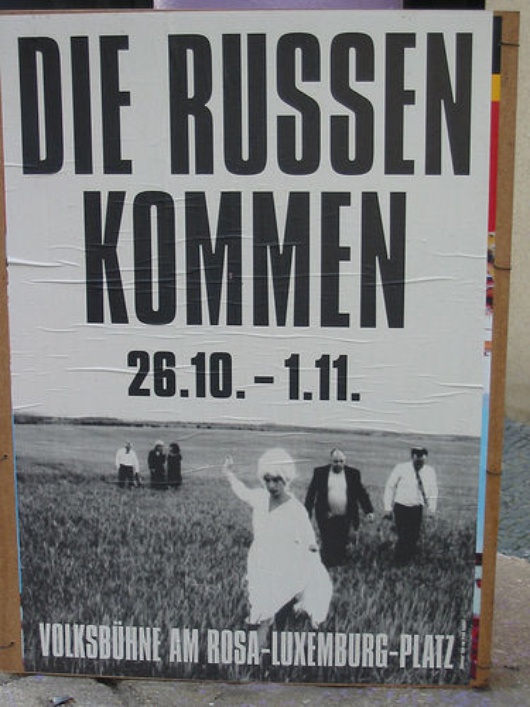

In-text photos: Marzahn (LutzSchramm/ Flickr), exposition on Russians in Berlin (new9678/ Flickr)

Translated from Russes allemands : Berlin en héritage