"Frontera invisible", the dark side of biofuels

Published on

Translation by:

Nadège ValletFrontera Invisible, a documentary about the dark side of biofuels, produced by NGO Transport & Environment, premiered on February 7 at the European Parliament . Cafebabel talked to Nico Muzi, one of the film makers, who observed with his own eyes the consequences of palm oil production in Colombia.

Many people are aware of the issues resulting from palm oil in food, especially since the Nutella case in France and its consequences on the environment. Greenpeace directed a series of videos reinterpreting Kitkat advertisments, to alert Nestlé on their role in deforestation and its consequences on the orang-utans' natural habitat.

In this documentary, Nico Muzi highlights two issues generally unknown from the general audience and resulting directly from palm oil: the human impact through deforestation, forest exploitation, land appropriation to produce palm oil and, of course, the cause of this extensive use: biofuels.

Biofuels are not entirely beneficial

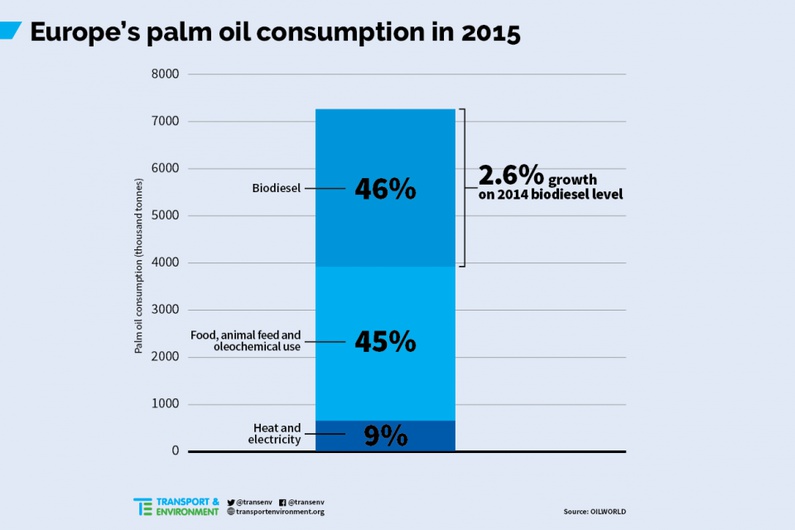

European law promotes biofuel use. Indeed, as part of the directive on renewable energies, « member States are required to use up to 10% renewable energies for transportation by 2020, in accordance with the EU2020 strategy» , Muzi says. This directive generated a significant increase in demand for biofuels, especially biodiesel. According to OILWORLD, 46 % of this type of oil is consumed via biofuels used in our cars and trucks.

Yet, such a consumption has tremendous effects on the people living in the exploited regions. Colombia, as it is shown in the documentary, is a striking example. The exploitation causes population displacement, urban exodus and armed conflicts between the FARC and far right paramilitaries. Armed groups are fighting each other for the land. More often than not, this results in the killing of many civilians.

Yet, such a consumption has tremendous effects on the people living in the exploited regions. Colombia, as it is shown in the documentary, is a striking example. The exploitation causes population displacement, urban exodus and armed conflicts between the FARC and far right paramilitaries. Armed groups are fighting each other for the land. More often than not, this results in the killing of many civilians.

Serious violations of human rights are being perpetrated in the Santa Marta, Choco and Meta regions, but the government prefers to ignore the issue. The documentary shows a speech from president Juan Manuel Santos, praising oil palm production while titally occulting its dark side.

Nico Muzi is depicting the inhabitants of these regions, through the testimony of farmers, fishermen and ranchers. Nico reminds us that many of these Colombians were forced to leave their homes in the early 1990s because of the civil war. « They were told that the government was going to eradicate the armed groups and that they could go back home after that. But when the campesinos went back to their lands in 2000, they found that they had all been planted with palm trees. Besides, armed conflicts were still going on". This is a difficult situation and there's no saying how this will end. « Up until now, there was still unexploited lands, because the FARC held the ground. Now that peace has been restored, we can wonder what will happen to these lands.»

Benefits, but not for everyone

« To make a viable production, i.e. profitable, you need about 3,000 hectares of land, it is a massive investment for a local farmer, and so they can't afford to engage in this activity». Industries are consequently who take the lion's share and employ local workers for the production. « And there's also more parasites due to monoculture” which implies using expensive pesticides. »

However, with a80% yield, palm oil is the most popular biofuel and the cheapest too. Yet the collateral effects of its production generates more greenhouse gas than fossil fuel - three times as harmful on climate.

Expansion of oil palm production is indeed causing deforestation and peatland draining in Southeastern Asia, South America and Africa. These are some of the areas hit by the same consequences than Colombia, like the Congo Basin and Liberia, a country who used to have the largest forest area in all Western Africa. Laurence Wete, a member of Cameroonian NGO FODER, and Jonathan Yiah, from Liberian Sustainable Development Institute, shared their experiences. In Africa, a huge area of the forest is often sold to foreign multinational corporations. Most of the time, inhabitants of these regions are not getting any of this money.

What are the alternatives?

« It takes a football field of any biofuel monoculture to power a car, while the same surface area of solar panels could power 100 electric cars » , Nico says. For him, the solution lies in solar, water and wind powers. These alternatives would be much more effective than biofuels and less harmful to the environment.

Translated from « Frontera invisible », le côté obscur des biocarburants