From San Diego to Vilnius: all Jew you need for a library in Lithuania

Published on

There is nothing more multicultural in Lithuania right now than the new library which opened in the capital of this Baltic state on 16 December. The concept is simple: all books, films and music must be about either a Jewish subject, writer or artist

Films by Steven Spielberg will sit side by side with religious texts, books on synagogues in Turkey and photographs donated to the library, such as the one taken by the actor Leonard Nimoy, best known for playing Spock in Star Trek. Most of the items in this little shop in Vilnius will be in English, but the library will also hold texts in Russian, French and German. There is no limit on which language can appear in the Vilnius Jewish library, as long as the book adheres to Jewish criteria.

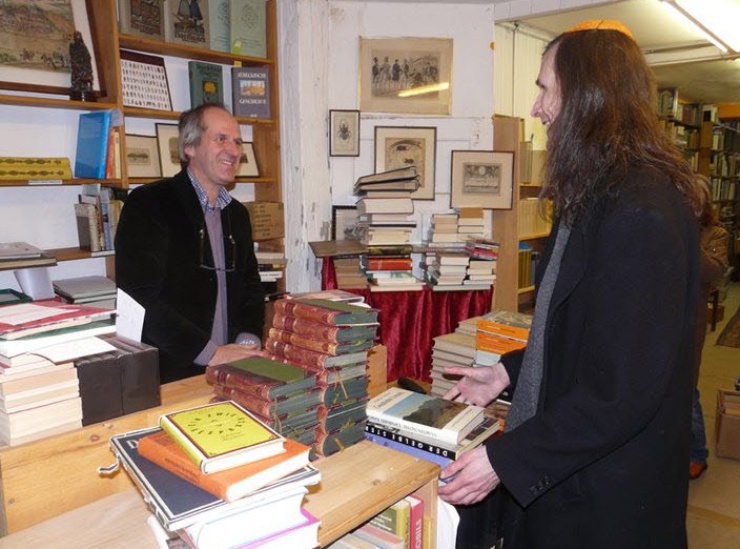

Wyman Brent, founder

The library’s unique collection was the brainchild of the American bookseller Wyman Brent, 49. He is neither Jewish nor has any familial ties to Lithuania. He is simply a lover of literature, who, seven years ago, came across a book from American writer Harry Kemelman’s Rabbi Small series in a bookshop in his home town of San Diego, California. The novels follow the adventures of a religious detective and were very popular in the 1960s and 70s. From there, his interest and his collection of books, films and memorabilia grew until he realised that he had to do something with it. The idea for the library was born.

Having first come to Vilnius on his travels in 1994 and fallen in love with its winding, cobbled streets, gothic cathedrals and rich Jewish heritage, Brent knew the library belonged here. In 2008 Wyman shipped his collection to Vilnius - about 4, 000 items in all - and started to look for somewhere to put it. ‘This new library can work out either way,’ says Olya Lempert, a translator and a library bibliographer who attended the only Jewish school in Vilnius. ‘It will either be a silly assortment of all sorts of stuff, or it can accidentally compile itself into a nice collection.’

Read 'Vilnius: ‘Jerusalem of Lithuania’' on cafebabel.com

The ministry of culture has given the library a part of a building on Gediminas Avenue, the main boulevard in Vilnius, and a grant of 700, 000 litas (about 200, 000 euros or 166, 813 pounds). Wyman, who has spent 50, 000 dollars of his own money on the collection, will become an ambassador-at-large for the library and will invite individuals and institutions to donate books. ‘For Lithuania’s future it is extremely important to be conscious of being part of a rich and diverse tradition of European culture,' says Arunas Gelunas, the minister of culture. 'This project will restore a part of the colourful mosaic of Vilnius. That helps us perceive the cultural heritage of our country in its full scope.’

Jews in Vilnius

Around 5, 000 Jews live in Lithuania (around 0.1% of the population) out of the 220, 000 or so who lived here before the second world war. Vilnius was a cultural hub of Kewish art and culture. Jews lived more or less in peace with their Lithuanian, Russian and Polish neighbours. Today, there is just a fraction left of Lithuania’s rich Jewish heritage (and hardly anything left of the many Jewish libraries that were functioning before the shoah). The Vilna gaon Jewishstatemuseum and its affiliate, the tolerance centre, work hard to educate Lithuania about the painful history of the holocaust, the full knowledge of which was largely blocked by the soviet union until Lithuania became independent (for the third time in its history) in 1990. Although many misconceptions remain between the Lithuanian and Jewish communities to this day, this year has been named the official ‘year of remembrance for the victims of the holocaust in Lithuania’. As Rachelė Kostanian, head of the holocaust exhibition at the Jewish museum says, there has been a noticeable change in society in the last few years. ‘The holocaust has entered into people’s consciousness a little more.’

Jewish life is quite minimal in Vilnius as there are so few of them left, and revolves mostly around the jewish community centre. Located in a lovely, grand old buidling which was formerly a Hebrew ‘tarbut’ school, here members of the community gather to learn Yiddish, a nearly forgotten language which was widely spoken before the war. The centre also organises dance evenings and trips to the countryside for young school children. Youth group organiser Valentin comes from a mixed family - his father is Jewish while his mother is Russian. Yet he strongly identifies with his Jewish background, to the extent that he has designed his own tattoo of the hamsa hand (a popular jewish symbol of good luck) on his forearm and shows it off proudly.

General support

Valentin is not a fan of libraries, but is pleased about the new opening and promises to look in. Likewise the wider Jewish community supports the new library, though some harbour concerns that this new project might be manipulated by the government, either through dictating what will be in its collection or through using it to show the western world that Lithuania is doing something about its lost heritage. ‘Just because a Jewish lady has written a book about gardening doesn’t mean it adds anything to Jewish culture,’ remarks the head librarian of the Jewish museum library, Rosa Levitaite. ‘It’s more of a foreign languages library.’ Wyman doesn’t dispute that fact. He hopes to attract people who also wish to learn other languages and would like to watch films (such as 1953's The War of the Worlds, which qualifies because its star Gene Barry is of Jewish origin) and attend talks. ‘This library is not just for the Jewish community, it is for everyone. I want people to know about what Jews have contributed to the world.’

Is there even much demand for Jewish culture among Lithuanians? ‘The library has something that could be intriguing for young people, especially if they hold events, exhibitions or meetings with interesting people,’ says Teklė Kavtaradzė, a script-writing student. Olya Lempert will go to see what Brent has gathered. ‘Hopefully it will attract some positive attention and visitors will want to investigate further,’ she says. That is the point. Wyman promises to promote all Jewish cultural institutions in the library and hopes that people will make positive connections, like he did all those years ago when he picked up the Rabbi Small book. ‘I read that book and look at me seven years later. You never know what people might find in the library for themselves.’

This article is the second edition in cafebabel.com’s 2010-2011 feature focus series on multiculturalism in Europe. Thanks to the team at cafebabel Vilnius

Images: main (cc) Casey David/flickr; in-text: Wyman Brent © Vilniaus zydu biblioteka 10-03, google plus page © Zilvinas Beliauskas; library © official page of the Vilnius jewish library/ video (cc) Bessie 1991/ youtube