From Ireland To Greece: Europe's Youth Take the Cuts

Published on

The recent decision by the Irish government to cut jobseekers' allowance for under-25s is just the latest in a series of discriminatory policies against young people that have been introduced in Europe in the last few years.

It's not easy to be young in Europe these days, particularly if you are among the 5.5 million young people in the EU that are unemployed. With the scourge of youth unemployment constantly in the headlines, and increasing demands for concerted action, governments are hitting back. But instead of focusing all their energy on the labour market inequalities, financial corruption, greed and cronyism that created and exacerbated the crisis, some are hitting back at the young people themselves.

Like it or lump it

On 16 October the Irish government announced that it would reduce jobseekers' allowance for new entrants aged under-25 to €100 per week as part of its budget for 2014. People aged 25 will also get a reduced rate of €144, and only those aged 26 and upwards will get the full jobseekers’ rate of €188. In the Dáil (Irish parliament) some of the opposition parties and independents expressed concern at these measures, which smack of discrimination. Thankfully parliamentarians on the government benches explained that they wanted to ‘incentivise’ youth employment, and save young people from lying around watching flat-screen TVs all day. To make such a comment about any another age group would be unthinkable, but it seems that young people are fair game.

The National Youth Council of Ireland have labelled the cuts "disproportionate and unfair” and have warned that they will create further hardship for young jobseekers and accelerate the number of young people emigrating from the country. Shortly after the budget was announced, youth campaigners formed a mock airport queue outside the Irish parliament to compel the government to reverse the decision, but the protests fell on deaf ears. Young people would have to like it or lump it.

‘Earn or learn’

Targeting young people for cuts is à la mode in Europe at the moment. At the start of October the British prime minister gave his 'Earn or Learn' speech at the Conservative Party conference, proudly proclaiming that housing benefits and job seekers' allowance will be denied to young people if his party wins the next election. Rather than being a discriminatory and punitive crackdown on young people, David Cameron has presented the policy as a ‘bold’ move that would help Britain become the ‘land of opportunity’.

Over on the continent the Netherlands has had its own 'earn or learn' policy in place since 2005. In Belgium the stage d'attente or 'waiting period' for young people to access unemployment benefits was extended to twelve months in 2011, a policy that civil society organisations said could increase youth poverty and social exclusion.

The message is clear – ‘get a job or go back to college’, even though jobs are more difficult to come by than ever and tertiary education has never been more expensive. But if you are a young person living in the UK or Greece, even if you get a job the chances are you will make dramatically less than everyone else, solely because of your age. The UK has had a lower ‘development’ minimum wage for young people aged 18-20 for a number of years. In 2012 the age-wage gap became even bigger when the youth wage was frozen while the minimum wage for the older population was increased. In February 2011, under pressure from the troika (the IMF, the World Bank and the European Central Bank, Ed.), the Greek government reduced the general minimum wage by 22%, whereas the minimum wage for young people was cut by 32%. This decision was implemented despite the fact that Greece has amongst the highest levels of youth poverty in Europe.

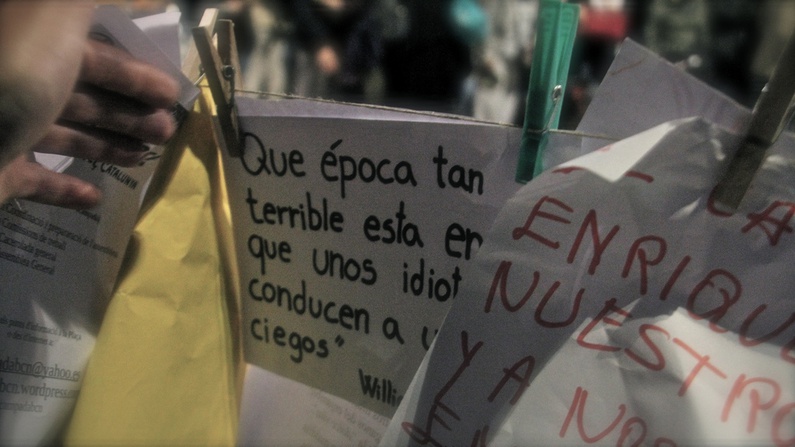

Sending a message back

Sending a message back

As governments push ahead with these policies, young people are being pushed further into poverty and closer to desperation. Young people are more likely to be living in poverty than elder people, and levels of inequality between the generations are increasing with each new punitive measure imposed on the young. Since the onset of the economic and financial crisis, the risk of social unrest has increased by 12% in the EU, with the sharpest rises seen in countries with the highest levels of youth unemployment.

It is difficult to know what the consequences of these policies will be in the long run, but young people will not improve their situation by disengaging from the political process, or allowing destructive elements to discredit their legitimate grievances. They must organise, agitate, demonstrate, articulate their demands, and most importantly, vote. The European Parliamentary elections next year will provide the opportunity to send a powerful message; Europe's youth cannot be ignored, and furthermore they will not tolerate discrimination.