French citizens ‘Balkan-level’ skill at the English language

Published on

The nineteenth-century attitudes to language learning here are not just wasting people’s time, but wasting an extraordinary amount of their money, opines a young Irishman who teaches English in Paris, capital of a country which an 'archaic' education system

‘ZE’. This is the first word I usually put on the blackboard when teaching English in France. Pronouncing it is forbidden. Each time a student neglects to fully articulate his aspirated TH, all I have to do is cast a mock-serious eye at that ‘ZE’, and he knows to correct himself. Experience has taught me that in France it is necessary to start with the basics. Last year, according to the official results obtained in the TOEFL exam ('Test Of English as a Foreign Language'), France was ranked 69th in the world - only a few points ahead of what French daily Le Monde candidly referred to as the ‘dunces of Europe,’ Kosovo, Cyprus and Albania.

Top of the flops

It is an obstinate stereotype that the French ‘refuse’ to speak English to foreign visitors. This does nothing to help the fact that thousands of promising French students every year have their choices severely limited simply because they cannot speak English. Perhaps it is time that the French government took note of the old accolade ‘there is no such thing as a bad student, only bad teachers’. ‘France,’ according to Marie-Sandrine Sgherri of French weekly Le Point, ‘produces the worst English teachers in the world.’

‘France produces the worst English teachers in the world’

The French education system is cripplingly archaic. This becomes apparent within the first few hours of teaching English in France. Students recite entire sentences by heart without knowing what the individual words mean. They generally have an absurdly intricate knowledge of the phonetic alphabet, but have little to no clue how English words should sound when spoken out loud. They sigh in relief at verb tables and tenses, but panic when asked to give a practical example. When I first started teaching in Paris I was baffled by the acute linguistic deficiencies of my students. I had just come from Switzerland, where students speak the same French, but have none of the same problems when it comes to learning English. So where did the French system go so wrong? According to American author Laurel Zuckerman, it all comes down to one little exam; the infamous agrégation d’Anglais.

Aggregating your English?

The agrégation is a notoriously difficult civil service exam through which students from all over France compete for a teaching position within the enormous government body of the national education. The aim is to select the next generation of English teachers in France. The problem is, you don’t have to speak particularly good English in order to pass. In fact, as Zuckerman discovers, being a native speaker is a handicap to succeeding in this bizarre language test.

In her investigative account Sorbonne Confidential (2009), Zuckerman explores the extraordinary world of the agrégation and its role in producing the ‘worst English teachers in the world.’ More than half of this exam is entirely in French, and a large proportion of the English section involves a translation from French. Until 2009, one of the primary components of the exam was the ‘leçon,’ an oral presentation that was not only to be delivered entirely in French, but was judged on the candidate’s eloquence and mastery in the French language. Not only this, but the candidate must write a dissertation in French, to be strictly composed according to the Cartesian principals that are taught in French secondary schools - a difficult feat for even the most fluent of foreigners. This is all for an exam to become an English language teacher.

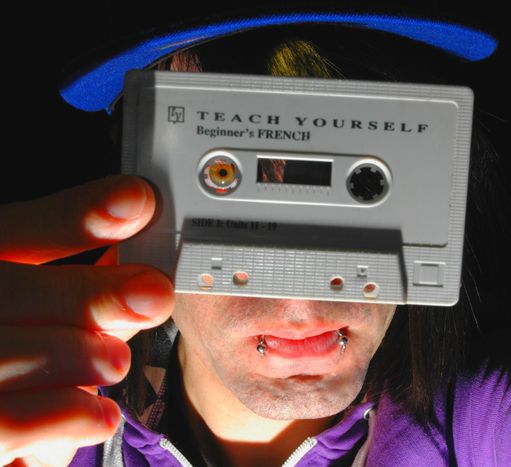

This summer, I was approached by a young British mother, who had moved with her family to Paris, and wanted me to give English lessons to her son. ‘It’s just,’ she said anxiously, ‘that they don’t really do English here.’ I nodded. ‘I went to see the English teacher, at the school, and well, to tell you the truth, she could hardly string a sentence together.’ Metros and buses in France are plastered with advertisements promising language sessions with native speakers for top prices, while France’s famous system of public education is failing, year after year, to teach its young people English.

This summer, I was approached by a young British mother, who had moved with her family to Paris, and wanted me to give English lessons to her son. ‘It’s just,’ she said anxiously, ‘that they don’t really do English here.’ I nodded. ‘I went to see the English teacher, at the school, and well, to tell you the truth, she could hardly string a sentence together.’ Metros and buses in France are plastered with advertisements promising language sessions with native speakers for top prices, while France’s famous system of public education is failing, year after year, to teach its young people English.