Freedom of Speech: Can We Laugh About Anything?

Published on

Translation by:

Sofia RabatéIn France, humour is quasi canonised by a phrase from comedian Pierre Desproges, "you can laugh about everything but not with everyone," a principle by which Charlie Hebdo abided. But what about other European countries?

At the editorial board, during certain conferences, or while getting drinks, we usually fall into the most obvious cliché. In general, we joke around. Sometimes we're offensive, reaching the limits of nice camaraderie to gently drift towards debating and an exchange of ideas. Katha knows this very well. During the eight years she has spent in France, the thirty-year-old German woman has seen the effects of Godwin's law (the eternal evocation of Nazi Germany in a long conversation — Ed.) more than anyone else. When, while going out, we asked about Hitler, she admits that it still "pisses her off." "Yet, in Germany, I feel like things are changing," she adds. "Before, we didn't really laugh about Hitler. But in 2013, a parody focused on him became a best-seller (Er ist wieder da, "He is returning" by Timur Vermes — Ed.)."

The Jewish taboo

In Germany, Katha clarifies that in theory, one can laugh about anything. "That's, in any case, what the law says, and what Kurt Tucholsky (German journalist and writer from the early 20th century — Ed.) proclaimed for all eternity with his famous quote: "Satire has every right." Today, satire can even be Martin Sonneborn (leader of Die Partei and editor-in-chief of the satirical journal, Titanic — Ed.) sit with the European Parliament." Yet, according to her, there is one real taboo that even the subtlest of humorists wouldn't dare break: the Jews. "This still, and always, creates unease. It's awkward, embarassing. Not funny." This may seem strange, but Germans have this in common with the Italians. Cecelia, newly arrived in Paris, explains that it would never be possible to go onstage with a jibe directed at the Jewish community. "It's something that we do secretly, with close friends," she says, almost whispering. "In Italy, the Holocaust still has a real influence on young people."

Under the media's radar, Italy fears the omniscience of another religious community: the Catholic Church. Aided by the Vatican, it remains, in all senses of the term, a State within the State. "Whether it's for a theatre play, a satirical show, or a drawing, the church maintains a considerable influence over how this type of message is recieved within the public opinion," Cecilia explains. She cites as proof the extraordinary case of the Italian monthly satirical jounralIl Vernacoliere that, in 2005, published a caricature of the former pope Joseph Ratzinger also known as Benedict XVI. The journal was never condemned, but the church used a "completely imaginary" law to exert its power: "infraction against the Catholic religion and contempt for the Pope."

Under the media's radar, Italy fears the omniscience of another religious community: the Catholic Church. Aided by the Vatican, it remains, in all senses of the term, a State within the State. "Whether it's for a theatre play, a satirical show, or a drawing, the church maintains a considerable influence over how this type of message is recieved within the public opinion," Cecilia explains. She cites as proof the extraordinary case of the Italian monthly satirical jounralIl Vernacoliere that, in 2005, published a caricature of the former pope Joseph Ratzinger also known as Benedict XVI. The journal was never condemned, but the church used a "completely imaginary" law to exert its power: "infraction against the Catholic religion and contempt for the Pope."

Car accidents and God's anger

This influence is not necessarily derived from a taboo. There are many who speak of self-censorship to describe the feebleness of the media and society when making fun of certain institution. In Poland, one could even speak of "fear." Pia, a Polish woman living in Paris, affirms: "Polish people don't laugh about the things they're afraid of, as to not provoke them. And the Polish are afraid of two main things: car accidents and God's anger." If you open a Polish newspaper, in a country where nearly 80% of the country identifies as Catholic, it will be hard to find a satire of the Pope or of Jesus. In 2015, does the newer generation try to draw outside of what is imposed? "The new generation has an attitude that is less conservative and less regressive," Pia answers. "But it is mostly characterised by one thing: 'I-don't-give-a-shitism.'"

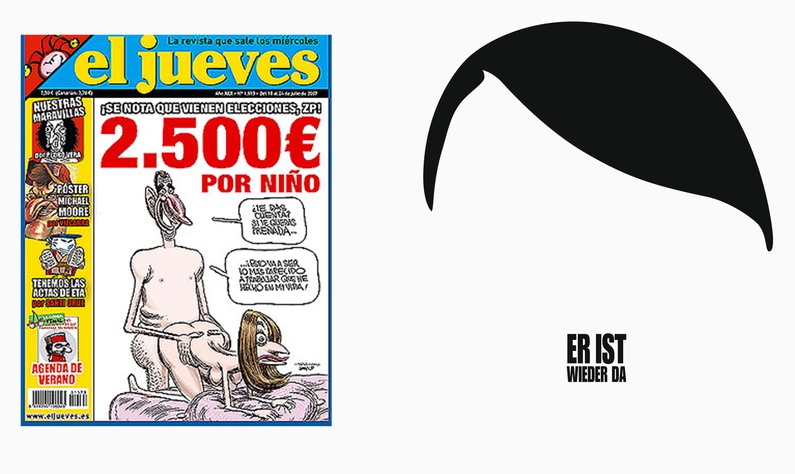

On the other side of the Pyrenees, humour has a price, and the inflation is decided by the mood of the royal family. According to Spanish laws, libel and slander of the monarchy are punishable by a minimum of two years in prison. Ainhoa, a young Spanish woman aged 23, laughed when she first saw the cover of El Jueves, showing Felipe VI, the Spanish king, taking his wife doggy-style. The problem is that the country had to wait until the image made its way onto the Internet to laugh at it. The day of its publication, a judge confiscated the special edition of El Jueves when it was supposed to be distributed. Other publications had the same fate, but the Spanish judicial system isn't necessarily a reflection of a society that does laugh outside of the courtrooms. When asked if in Spain nothing is taboo, Ainhoa looks upwards, thinking, before saying: "I'd have said Francoism, but actually, we laugh about that, too. When we're going out, or with family, we make fun of everyone: the queen, the king, the gypsies, the poor, the homeless..."

On the other side of the Pyrenees, humour has a price, and the inflation is decided by the mood of the royal family. According to Spanish laws, libel and slander of the monarchy are punishable by a minimum of two years in prison. Ainhoa, a young Spanish woman aged 23, laughed when she first saw the cover of El Jueves, showing Felipe VI, the Spanish king, taking his wife doggy-style. The problem is that the country had to wait until the image made its way onto the Internet to laugh at it. The day of its publication, a judge confiscated the special edition of El Jueves when it was supposed to be distributed. Other publications had the same fate, but the Spanish judicial system isn't necessarily a reflection of a society that does laugh outside of the courtrooms. When asked if in Spain nothing is taboo, Ainhoa looks upwards, thinking, before saying: "I'd have said Francoism, but actually, we laugh about that, too. When we're going out, or with family, we make fun of everyone: the queen, the king, the gypsies, the poor, the homeless..."

The politically correct Anglo-Saxon

The debate on the limits of freedom of speech, which presents itself with more acuteness since Wednesday's killings, has a greater echo in the United Kingdom as well as in other Anglo-Saxon countries. The choice the media has made to not publish the caricatures of Charlie Hebdo testifies to this. Is irreverent humour possible in societies that are extremely concerned about the unity of their different communities? "I would say that we never make fun of characteristics of people that are tied to religion, race, gender, handicap, sexuality..." explains Kait, a Canadian journalist that has already spent a lot of her life between Europe and America. She continues: "Canada is maybe the most politically correct country in the world. I'm always shocked when I hear French people making jokes that I consider racist, sexist, and homophobic. It's possibly the greatest culture shock that I have experienced in France, and in Europe in general."

Each country in Europe would then have its own sensibility, its more or less acknowledged taboos. The universal concern with humour, as with any type of message, is that we can't separate the content from the style. And the subject, vast and eminently complex, will always have its own questions: when has one gone too far? How do we distinguish mistake from fault? Parody from real stance? Good or bad humour from being humorous? In France, behind the liberty, the subject has its own problems, whether or not it is (not) Charlie or Dieudonné.

Each country in Europe would then have its own sensibility, its more or less acknowledged taboos. The universal concern with humour, as with any type of message, is that we can't separate the content from the style. And the subject, vast and eminently complex, will always have its own questions: when has one gone too far? How do we distinguish mistake from fault? Parody from real stance? Good or bad humour from being humorous? In France, behind the liberty, the subject has its own problems, whether or not it is (not) Charlie or Dieudonné.

Translated from Liberté d’expression : peut-on rire de tout, ailleurs en Europe ?