Frank Pe, Luc Schuiten: eco-dreams of Brussels' comic book art architecture

Published on

Translation by:

Cafebabel ENG (NS)Not everyone knows it but another Brussels does exist which is more green, more romantic, more human. It's the one which burgeons in the imagination and designs of those who have learned to love Brussels as it is, with its contradictions, its unbridled path of illogical construction and 'forced' cohabitation between the two souls of Europe, one Latin, the other Germanic.

A comic book artist, visionary architect and artist-editor explain how they dream of a different Brussels.

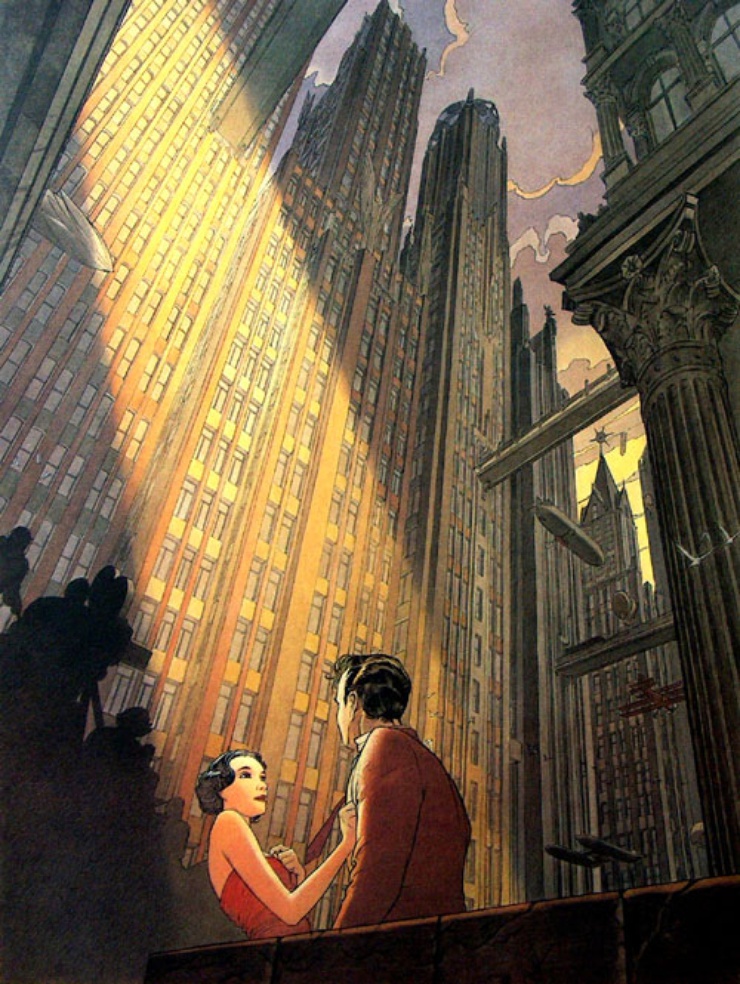

'A city which was sold to the appetites of politicians and sponsors a century and a half ago,' begins the cult comic book Brüsel (Cities of the Fantastic). Its creators François Schuiten and Benoit Peeters have staged and illustrated an authentic parallel city which is stifled by the phenomenon of the European capital's 'brussels-isation'. It's the story of a florist who is convinced that progress will only come through the 'plastic goddess', a solution to organic degradation. The entire city around him is victim of a project of systematic dehumanisation, the work of a megalomaniac businessman.

It's not hard to spot the transformations which Brussels has undergone in reality. That's thanks to the foolishness of the mayor of Brussels, Jules Anspach, who was obsessed with the grand boulevard, geometric style of Haussmann Paris. In 1865 he commissioned the architect Leon Suys to cover up the river Senne. The now phantom waterway once crossed the city, at one point to be covered over by the north-south railway. It disfigured the city once it was emptied out in a vicious circle of destruction and reconstruction which ruined the architectural patrimony of the capital.

Being called an architect in Belgium is one of the worst insults you could hurl

Brüsel (published in English nine years after its original Belgian release in 1992 - ed) is more than just a comic book. It's an anti-liberal pamphlet which shows the still open wounds of a city overwhelmed by progress, steel and cement. After having read it, it's clear why being called an architect in Belgium is one of the worst insults you could hurl.

Luc Schuiten

Fortunately, I meet one who is a little more particular. Luc Schuiten is François's brother, who has an air of a mad scientist and sports a calming smile. He's a visionary architect who has spent years designing and believing in another, completely sustainable Brussels. His home is his studio, a kind of worldly paradise where it's quite likely to stumble upon an oak tree in the living room. 'The difference between my brother's comic book and my work,' begins the 66-year-old, 'is that he is trying to tell a story whereas I am not interested in fiction, but rather conceiving another possiblity. My work is not about dreams but the construction of a concept which can become reality if we want it to. It's what the Americans did when they sent a rocket to the moon. They created the idea and did everything they could to make it happen. My project is less ambitious than walking on the moon, but no-one wants to invest in it. My 'natural' world doesn't please those who are in power.'

Luc is not a fan of our world. 'It's founded on continuous growth,' he complains. 'That's unthinkable considering the fact that our resources are limited. Our systems of boundless acceleration will lead us into catastrophe.' However, Luc's vision is a positive one of a 'city of lights' which contradicts the darker city that Brussels is today. 'A world without petrol, industry and the power of money is a more beautiful world,' emphasises Schuiten, whose parents were also architects. With the way things are, it feels like nobody wants that world. 'I work with the living as if they were construction materials. It's a thousand times more functional and resistant than industrial materials. Unfortunately, the technique has only been developed for military needs. Even sewing machines were invented because the military needed them. Humanity's greatest progress has emerged out of the need to attack a neighbouring country and not to improve the planet. That doesn't interest leaders.' According to Luc, the world only has seventy more years left in it. 'Politicians persist in their beliefs of a city in perpetual growth. It's about working more, producing more and consuming more. Brussels is the victim of politicians who have short-term preoccupations. The important thing is to resolve the little problems or even more simply, to form a government! No-one wants to invest in a more human world.'

Luc is not a fan of our world. 'It's founded on continuous growth,' he complains. 'That's unthinkable considering the fact that our resources are limited. Our systems of boundless acceleration will lead us into catastrophe.' However, Luc's vision is a positive one of a 'city of lights' which contradicts the darker city that Brussels is today. 'A world without petrol, industry and the power of money is a more beautiful world,' emphasises Schuiten, whose parents were also architects. With the way things are, it feels like nobody wants that world. 'I work with the living as if they were construction materials. It's a thousand times more functional and resistant than industrial materials. Unfortunately, the technique has only been developed for military needs. Even sewing machines were invented because the military needed them. Humanity's greatest progress has emerged out of the need to attack a neighbouring country and not to improve the planet. That doesn't interest leaders.' According to Luc, the world only has seventy more years left in it. 'Politicians persist in their beliefs of a city in perpetual growth. It's about working more, producing more and consuming more. Brussels is the victim of politicians who have short-term preoccupations. The important thing is to resolve the little problems or even more simply, to form a government! No-one wants to invest in a more human world.'

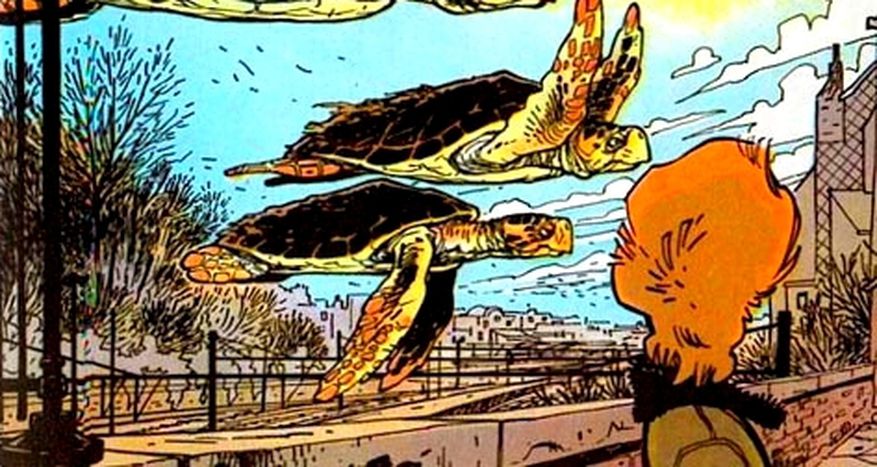

Heritage of 1968: Frank Pé

An entire generation needs sustainable degrowth. Frank Pé, a famed comic book artist from Brussels, is one of those who was speaking up against the excesses of neo-liberalism and the instrumentalisation of ecological passion even before 1968 and the birth of green political parties. He no longer lives in Brussels but he's here to meet me today at the Belgian comic strip centre to talk about his work. He's a student of the first generation of Belgian comic book artists which include Hergé and Andre Franquin. The latter's 1957 creation Gaston for the comic strip Spirou promotes biodiversity and has been a symbol for organisations such as Greenpeace. Frank Pe's character Broussaille (1978) is the symbol of love for nature and animals, though without militant intentions. 'Ecology is different from politics,' precises Frank. 'Ecology is based on equilibrium and biodiversity whilst power enters in the concept of politics. There can't be any equilibrium where there is power, but rather the opposite. I don't have any pedagogical interests in my work. I just want to share my passion for nature's incredible creativity.'

As a child, Frank Pe says it was easy to find green spaces in Brussels. 'Then they started to build everywhere with no logic,' he continues. 'There were no borders. Politics proved to be a fragile field, at least from the eighties onwards. It couldn't advance liberalism so it became an accomplice.' It seems to be a characteristic of the city of Brussels today. 'The real problem here is the lack of culture, the sensitivity towards the concept of patrimony.' In France culture is integrated in politics. In Germany there are laws which can state 'stop, the cement stops here.' Try looking for those limits in Brussels. Western society is heading for the abyss, according to Frank, 'ever since Freud placed the ego around the centre of behaviour. It justifies an individualism that doesn't take community into account.' The same can also be said for contemporary art: 'It doesn't enhance the meaning of life anymore, but addresses an intellectual niche, not society.'

Contemporary Belgian comic books: another form of engagement

Frank Pe is not a lover of contemporary art nor the new direction that the comic book industry has taken. Alternative publishing houses like Fremok, L'Employé du mois or La Cinquième Couche (5c) push back the limits of linguistic experimentation through images 'by always trying to find different ways of telling a story,' explains young Belgian writer Greg Shaw. He uses cinematographic techniques in his work, whilst others such as art teacher Michael Matthys use animal blood in their comic books. There's certainly some attention devoted to the environment, agrees Xavier Lowenthal, artist and editor at 5c. His group of characters includes figures of calibre such as the Italian Antonio Bertoliand the Chilean-Jewish comic book writer Alejandro Jodorowsky.

'Today a book lasts between one and three weeks, just like Nutella or sugar,' he tells me at his welcoming and disordered residence. 'The industry demands more production to feed even more sales, whilst drastically reducing the time between production and consumption. We (a little like all independent publishing houses – ed) are against speed. We feel that a cultural good should last for as long as possible. That's why we invented the 'mort au pilon', or 'death to the pile'.' The pilon is an enormous pile of books which are destined for the dustbin. Xavier and his collaborators resell these books at a price the customer chooses, and the intelligent anti-waste initiative runs annually for a week. 'We're victims of overproduction,' Xavier adds. 'It's all down to politics. It's the fault of the liberals if a city turns into a veritable hellhole between five and 6.20pm. They can't even give up their cars.'

Does a solution exist? 'There's nothing you can do,' Xavier replies. 'Capitalism is too strong. Your average Joe or Jane can't think in the long term because they have got to eat. It's up to the politicians and those who have the money but sadly they are too ignorant.' What's clear is this donkey race is destined to end, sooner or later.

This article is part of cafebabel.com’s 2010-2011 feature focus on Green Europe, which has already hit Budapest. Thanks to the team at cafebabel.com Brussels. Watch this space for Green Berlin, Green Rome, Green Seville and Green Paris

Images: ©Diana Duarte; ©courtesy of Frank Pé, François Schuiten, Luc Schuiten

Translated from L'altra Bruxelles: viaggio negli eco-sogni dei suoi artisti