France: When reactionary thinking is expressed through the ballot box

Published on

Translation by:

Kath Burns

Kath Burns

France's governing Parti Socialiste has now suffered a worryingly continuous series of setbacks in recent elections. The Front National (FN) is not only strengthening its position in the polls but also the power of its ideas at the heart of French society. With two years to go until the country's next presidential elections, what lessons can we learn?

The "Republican Front" has become a recurrent theme in French elections. The idea was to block the FN at all costs, despite disastrous economic policies and markedly poorer new voters – the main source of electoral fuel for the extreme right.

Prime Minister Manuel Valls has been at the forefront of this marketing campaign. Speaking on the Europe 1 radio network on 8th March last year, he said: "I'm scared for my country. I'm scared that it will crack in the face of the Front National." Judging by the state of the country's economy, there's more reason to be scared that France will crack from mass unemployment, and yet no ambitious proposals look set to be made.

The Republican Front isn't universally respected. Nicolas Sarkozy, who is now head of the UMP party, set himself apart by recommending "ni-ni" (neither nor) to his voters – neither the left, nor the FN. It was a way of implicitly putting his two rivals on equal footing, without denying the political affinities between the extreme right and his own party's conservative grassroots. In a political resurrection of the historic divide between the RPR (Rally for the Republic) and the UDF (Union for French Democracy) parties, Sarkozy's UMP and the centre-right UDI (Union of Democrats and Independents) party formed an alliance in order to come out on top of the country's local elections on the 22nd and 29th March, despite their differing stances towards Marine Le Pen's FN. What if the Republican Front's strategy was a way of avoiding having to assess its own economic and political track record?

Democratic frustration and an absence of economic solutions

Following the local elections, we are left with a governing party that continues to crumble, having lost half of the départements it controlled and which now runs 33 councils compared with 66 for the right. As for the FN, it went from having 1 councillor to 60, without winning any départements. The elections were also marked by the introduction of a new voting system, whereby candidates are put forwards in pairs made up of one man and one woman so as to ensure parity. This genuine democratic innovation strengthens our political representation, which we should all welcome. However, it's a shame that it can't guarantee a renewal of what politics offers us.

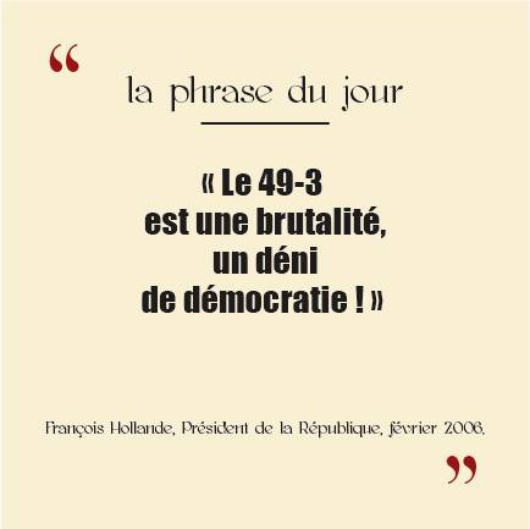

At over 50%, abstention remains the major player in these elections, which are a chance to punish the governing party. Electors are dissatisfied with what politics is offering them, and they feel a certain level of distrust in politicians generally. A perfect illustration of that is the rebels in the governing Parti Socialiste who are destabilising a Government that no longer enjoys a parliamentary majority. The use of article 49.3 of the Constitution to push through the economic reforms of the Macron law (named after France's Economy Minister) last February demonstrated a divide between the Government and the party's grassroots. Article 49.3 exposes the Prime Minister to the risk of a vote of no confidence, and its use was seen as a denial of democracy by François Hollande himself back in 2006 – a contradiction that the French people surely won't miss.

At over 50%, abstention remains the major player in these elections, which are a chance to punish the governing party. Electors are dissatisfied with what politics is offering them, and they feel a certain level of distrust in politicians generally. A perfect illustration of that is the rebels in the governing Parti Socialiste who are destabilising a Government that no longer enjoys a parliamentary majority. The use of article 49.3 of the Constitution to push through the economic reforms of the Macron law (named after France's Economy Minister) last February demonstrated a divide between the Government and the party's grassroots. Article 49.3 exposes the Prime Minister to the risk of a vote of no confidence, and its use was seen as a denial of democracy by François Hollande himself back in 2006 – a contradiction that the French people surely won't miss.

The FN's ideas are gaining ground amid widespread apathy…

The two-party system has gone back and forth between the left and right for the past 40 years, without ever fundamentally renewing what politics offers. What's more, the potential intellectual complicity between the economic leanings of the right and the so-called "social-liberal" left offer no opportunity for a democratic alternative today (Read: Le mystère de la rose bleue). Political change now tends to be in the form of messages, rather than ideas. Nicolas Sarkozy is currently working on a new name for his party, but will changing its packaging be enough? Shouldn't we try to tackle the FN with ideas, rather than legitimise its political position because we refuse to take risks? What meaning can we attach to a political structure that's focusing on 20th-century trends without updating its political software to reflect current issues?

In a France that was awakened in 2015 by Michel Houellebecq, Éric Zemmour and the Charlie Hebdo attacks, how can we not stop and reflect on these issues? What about the popular acceptance, almost as if by default, of Marine Le Pen's party as a credible political alternative? That's the bleak picture that Raphaël Glucksmann paints in his recent book Generation Hangover, a guide to the fight against reactionaries in which he explains that political battles are above all about the strength of ideas. French people's views about the death penalty, the European Union and immigration levels are evolving, and have radicalised drastically in less than four years. In the political sphere, those ideas now take the form of the FN. Since traditional political elites have failed to address it, this ideological shift can only be counterbalanced by a collective wake-up call.

The rise of reactionary thinking and its impact on voting should make us stop and think now more than ever. We can no longer hide from it, because next up is the presidential elections, and the Republican Front's wild card just might not be enough.

This article was originally published on Politicus.

Translated from France : quand la pensée réactionnaire se traduit dans les urnes