Fishing ban increases drug-trafficking

Published on

Translation by:

Jo Ashworth

Jo Ashworth

Despite the new EU’s new fishing agreement with Morocco, fishermen in Andalusia fear for their future

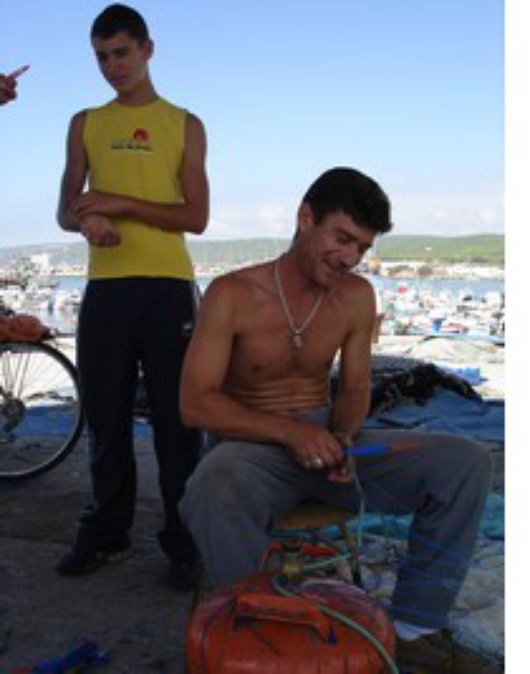

In the coastal village of Barbate, south of Cádiz, the inhabitants have patiently faced the strong Mediterranean winds for thousands of years. The easterly wind is often squally, treacherous and dominating. When it blows, doors slam, people are blinded with sand, and the streets and sea are emptied of people. It is a wind for which there is no solution but to wait. The port in Barbate has developed great patience. They wait for a break in the weather so they can go out fishing. The piers are full of men with rough, calloused hands repairing their nets with agile, mechanical and accurate movements. Their gaze periodically turns to the horizon, to the blurred African coast only 20 kilometres away, across the Straits of Gibraltar.

In the coastal village of Barbate, south of Cádiz, the inhabitants have patiently faced the strong Mediterranean winds for thousands of years. The easterly wind is often squally, treacherous and dominating. When it blows, doors slam, people are blinded with sand, and the streets and sea are emptied of people. It is a wind for which there is no solution but to wait. The port in Barbate has developed great patience. They wait for a break in the weather so they can go out fishing. The piers are full of men with rough, calloused hands repairing their nets with agile, mechanical and accurate movements. Their gaze periodically turns to the horizon, to the blurred African coast only 20 kilometres away, across the Straits of Gibraltar.

Glimmers of hope

So close, yet so far. Since the last Morocco Fishing Agreement expired in 1999, crews have been forbidden to fish in the plentiful waters to the north of Africa. Some have been given up, while others survive thanks to subsidies and perseverance. Since then, more than 4,000 Spanish fishermen and over 10,000 people in the fishing industry have lost their jobs. Today the imminent ratification by the Moroccan Parliament of the new Fishing Agreement between the EU and Morocco will provide some relief for the fishing industry in Andalusia. Yet to the great dissatisfaction of fishermen, the region will be granted almost half of the 119 licenses issued by the European Commission, down from 541 up till 1999. Today, European crews will be allowed to fish 60,000 tons in Moroccan waters in exchange for 144 million euros paid by the EU. Spain still holds more than 80% of the licenses, while the rest have gone mainly to Portugal, France and Italy.

For the last 50 years, Francisco has used a small boat also named ‘Francisco’ after his father, and his grandfather. Like most fishermen in Barbate, he continued the family tradition and devoted his life to fishing according to customs dating back the golden era of the first half of the 20th century. “Look, do you see this line of moored boats?” he says, pointing to the small boats swaying next to the quay. “Thirty years ago there were so many boats they hardly fitted here,” he recalls. Lowering his gaze, he shakes his head and says that he is pleased that none of his five children wants to devote himself to working at sea. “Young people don’t want to get cold and earn little. Now they go and work in construction, or they go to the beach in the early hours of the morning to wait for the motor boats to arrive with the hash.”

No relief, no fishing

According to Francisco, “busquimanos”, young small-scale hashish traffickers, ride their mopeds to the beach in the early hours of the morning and pick up the packages of drugs delivered by small motorised boats. Although numbers have declined in recent years, the Spanish police force estimates that at least 10% of Barbate's population is either directly or indirectly involved in drugs trafficking.

Juan is one of the port’s youngest fishermen. He is 37 years old and has a 15 year old son who waves and shows off his small pet chameleon. “No, this one won’t go to sea, this one’s going to study,” says Juan. In the port of Barbate there is no relief for older generations. The majority of fishermen are retired but take to the seas in order to supplement their pitiful pensions and there are almost no fish in the waters. Juan’s boat was moored when the capture of certain species was banned for a few months in order to guarantee the sustainability of fishing. Even so, catches of tuna, Barbate’s “red gold”, have declined by 80% in the last six years. The fishing of anchovy and sardines is also dwindling due to competition from larger foreign boat. “The few that we do catch sometimes don’t even sell because frozen fish comes in from Italy, France and Morocco at rock bottom prices, and then what are we supposed to do?"

Juan is one of the port’s youngest fishermen. He is 37 years old and has a 15 year old son who waves and shows off his small pet chameleon. “No, this one won’t go to sea, this one’s going to study,” says Juan. In the port of Barbate there is no relief for older generations. The majority of fishermen are retired but take to the seas in order to supplement their pitiful pensions and there are almost no fish in the waters. Juan’s boat was moored when the capture of certain species was banned for a few months in order to guarantee the sustainability of fishing. Even so, catches of tuna, Barbate’s “red gold”, have declined by 80% in the last six years. The fishing of anchovy and sardines is also dwindling due to competition from larger foreign boat. “The few that we do catch sometimes don’t even sell because frozen fish comes in from Italy, France and Morocco at rock bottom prices, and then what are we supposed to do?"

Hope, nostalgia

Rafael has a boat named “Ana y Antonio”, after his children. With pride and nostalgia, he shows us hundreds more boats in a black and white photo album. He mentions that his father and the 40 other men sank aboard “El Alonso” and were never found. Rafael worked at sea from the age of six until he married. Now, at 47, he works as a builder and spends his free time in his warehouse at the port where he carefully stores he photographs and an enviable collection of 1940s cinema programmes. “There’s nothing to do here,” he complains as he looks over his “paper boats”, and recounts enough stories to fill the pages of a book. Rafael goes quiet and turns his attention back to the boats in his album, almost as fragile and vulnerable as those moored in the port, patiently wait for the wind to turn.

Translated from Barbate pesca en barcos de papel