Fighting For Clean Air In Krakow

Published on

Krakow is the second largest city in Poland. It's one of the country's tourist centres, with charming churches, museums, cafés and bars. But it also holds also the less flattering title of one of the most polluted cities in Europe. But thanks to a civil initiative fighting air pollution, the next generation of Krakowians might be breathing better air.

Slowly climbing up Krakus Mound, one of the four hills overlooking Krakow, we try not to breath too deeply. Despite the low temperatures and a cloudy sky, many Krakowians decide to spend their Saturday morning here, away from the city centre crowded with tourists. A few joggers, braving the cold in sleeveless shirts and shorts are running up the hill. My cafébabel colleagues and I just want to see what polluted air looks like.

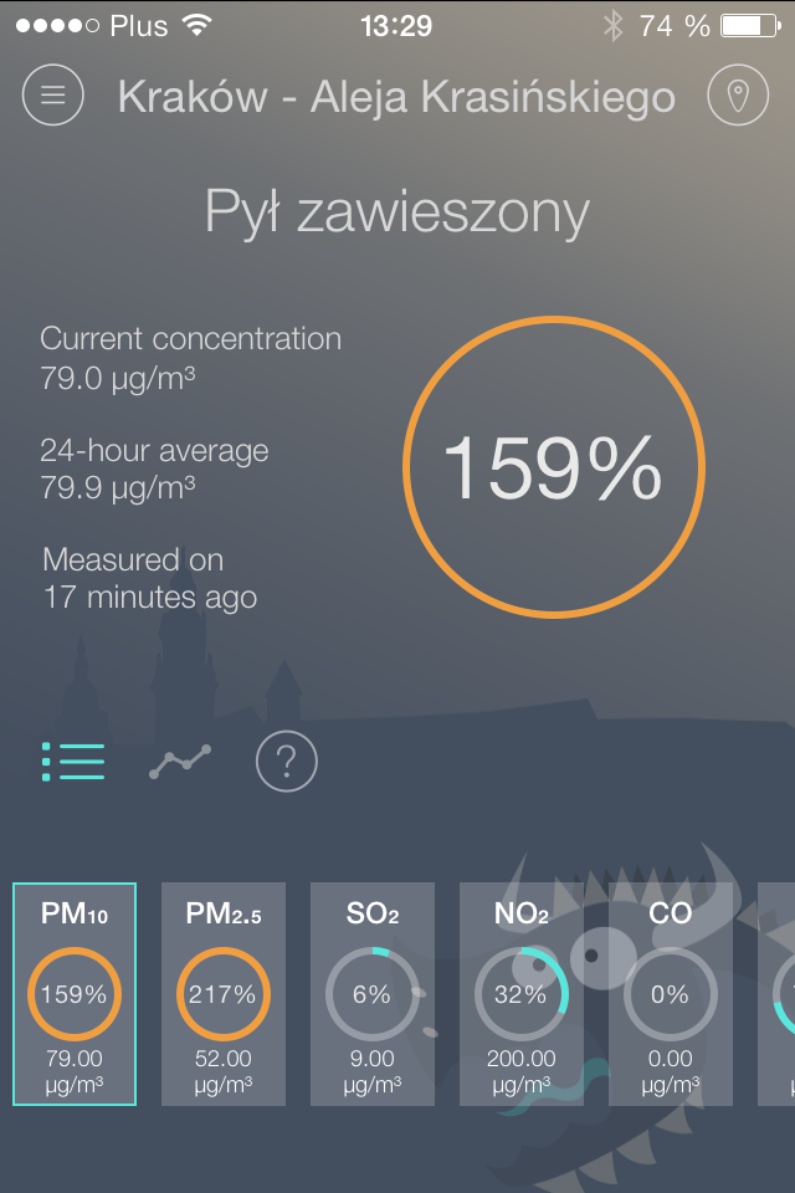

Poland’s second largest city is nestled in a valley. It is surrounded by hills and it is not blessed with much wind. These climatic conditions do not allow pollutant particles to disperse, making the city one of the most polluted in Europe. My newly installed phone app Smok-Smog measuring the air quality in Krakow, was showing that the pollution level exceeds the norm. Yet, from the top of a 200-and-something metre high slope, the mist enveloping the city did not look harmful.

Poland’s second largest city is nestled in a valley. It is surrounded by hills and it is not blessed with much wind. These climatic conditions do not allow pollutant particles to disperse, making the city one of the most polluted in Europe. My newly installed phone app Smok-Smog measuring the air quality in Krakow, was showing that the pollution level exceeds the norm. Yet, from the top of a 200-and-something metre high slope, the mist enveloping the city did not look harmful.

“In the back of your mind, you always know the air you're breathing is not good,” says Kamil, a student from Krakow. His mother, an opera singer, is constantly asked the same question by her foreign counterparts — how do you manage to sing here? "When they come to Krakow, already after the second rehearsal they feel as if their lung capacity has diminished."

“In the back of your mind, you always know the air you're breathing is not good,” says Kamil, a student from Krakow. His mother, an opera singer, is constantly asked the same question by her foreign counterparts — how do you manage to sing here? "When they come to Krakow, already after the second rehearsal they feel as if their lung capacity has diminished."

Air pollution can seriously damage your health. "It can even provoke suicides, because people get depressed," says Ewa, pointing her finger at a graphic brochure lying on the table in front of us. It is in Polish, but from the drawings I understand that air pollution can be linked to various diseases, from lung cancer to heart problems.

I meet Ewa Lutomska and Magda Kozlowska in a city center café called In de revolutionibus. The name is appropriate, considering Krakow Smog Alarm (Krakowski Alarm Smogowy), the human health advocacy group dedicated to improving air quality in the city to which they both belong, revolutionized the fight for clean air in Krakow. Ewa started the movement in December 2012 with two friends, Andrzej and Ania. With Magda, and Jakub, who joined a bit later, the group now counts five members, all from very different backgrounds. They don't define themselves as ecologists, just “ordinary citizens concerned about air pollution”. Today, Ewa lets Magda do most of the talking, only quietly interrupting her sometimes. They both seem fragile, looking half their age. But when they evoke their cause, their voices become stronger, passionate.

The fight for clean air started on the internet in December 2012 with a Facebook page. An online petition soon followed, and the first clean air march organized at the beginning of 2013 gathered some 300 Krakowians wearing gas masks. “At that moment the air quality program was debated on a national level. A program for Krakow recommended a ban on solid fuels, but it hasn't been voted in.” Ewa indicates the table of brochures. Colorful graphics show that the majority of Krakow’s winter air pollution comes from coal-powered domestic stoves, and just a minor part from traffic and industry. Besides coal, people sometimes burn garbage in their stoves, although doing so is forbidden. Bottles, plastic or “even nappies,” adds Ewa.

The fight for clean air started on the internet in December 2012 with a Facebook page. An online petition soon followed, and the first clean air march organized at the beginning of 2013 gathered some 300 Krakowians wearing gas masks. “At that moment the air quality program was debated on a national level. A program for Krakow recommended a ban on solid fuels, but it hasn't been voted in.” Ewa indicates the table of brochures. Colorful graphics show that the majority of Krakow’s winter air pollution comes from coal-powered domestic stoves, and just a minor part from traffic and industry. Besides coal, people sometimes burn garbage in their stoves, although doing so is forbidden. Bottles, plastic or “even nappies,” adds Ewa.

a funeral march for clean air

The type of pollution that matters is PM10. According to the World Health Organization, the acceptable concentration is 20 μg/m3. Krakow air quality monitoring stations regularly measure around 60 μg/m. During the winter which is stove burning season, temperatures drop to -30 degrees Celsius, and air pollution exceeds acceptable levels. "Last winter PM10 was around 300μg/m3,” Magda recalls.

Their initiative would have never have been successful if Krakow’s population weren't fed up with polluted air, Magda emphasizes. “We gave them a frame within which they acted,” she says. Some residents participated in a spamming project. “Over 2500 emails were sent to the local authorities in one night,” Magda evokes with a smile. In November 2013, almost 2000 Krakowians took to the streets to protest “in a funeral march for clean air. People wore black, carrying a coffin,” they recall. A month later, “the ban on residential solid fuel burning was voted in.

Their initiative would have never have been successful if Krakow’s population weren't fed up with polluted air, Magda emphasizes. “We gave them a frame within which they acted,” she says. Some residents participated in a spamming project. “Over 2500 emails were sent to the local authorities in one night,” Magda evokes with a smile. In November 2013, almost 2000 Krakowians took to the streets to protest “in a funeral march for clean air. People wore black, carrying a coffin,” they recall. A month later, “the ban on residential solid fuel burning was voted in.

Time for change

Later that day, I took the 502 bus to Nowa Huta, once a model of the ideal Soviet city, today Krakow’s eastern most neighborhood. In a city hall, nestled between concrete residential housing blocks, the local authorities opened an information point for all questions on heating appliance replacement. Even though nobody was queuing in front of her office when I arrived, Ewa Olszowska, director of the department of environmental protection, assured me that “they do get a lot of calls. People are interested mostly in if and how they can get a refund for changing their heating.”

The authorities mobilized regional and national structural funds for ecology to assure almost 100% subsidies for the replacement of the coal stoves, as well as additional subsidies for energy bills for the poorest households. All the coal stoves have to be changed before 1 September 2018 when the ban comes into full force. If not? “Solid fuel users will be fined and given an additional deadline to change their heating system.” But there is more to the fight than that. Ewa Olszowska unfolds a city map on her desk. Red arrows show the outline of the next big project; “redirecting the traffic to highways; promoting public transportation and parking outside of the city center; regulating the traffic lights in order to assure an undisturbed flow of traffic; all of that to keep car emissions outside the city,” she says.

Back in the café Revolutionibus, Ewa and Magda tell me, “Our fight isn’t over yet!” Happy with what they have achieved so far, they plan to keep an eye on the way the authorities implement new measures, but also to raise awareness of the pollution problem in other Polish regions. And why not in other countries too? “Krakow Smog Alert has become a sort of a brand,” they explain laughing, “so why not to export it?”

THIS ARTICLE IS PART OF A SPECIAL SERIES DEDICATED TO KRAKOW. IT'S PART OF EUTOPIA: TIME TO VOTE, A PROJECT RUN BY CAFÉBABEL IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE HIPPOCRÈNE FOUNDATION, THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, THE MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND THE EVENS FOUNDATION.