Feminism: Mamma mia is dead!

Published on

Translation by:

Jo Ashworth

Jo Ashworth

Edda Billi, a Tuscan who has spent more than 40 years fighting tooth and nail for gender equality, recounts the history of the feminist movement in Rome

A recent decision by the Italian Court of Cassation made it a crime to force a woman to kneel down and scrub the floor. The decision symbolises a potential new direction in a society where the rights of women are now being increasingly defended. However, the court has been branded as macho and conservative by feminist groups. Recently, it ruled that 'at work, an isolated and spontaneous smack on the behind does not constitute sexual harassment,' (although since September the High Court apparently changed their mind). On another occasion they ruled that a woman could not have been raped as she 'was wearing tight jeans.'

A recent decision by the Italian Court of Cassation made it a crime to force a woman to kneel down and scrub the floor. The decision symbolises a potential new direction in a society where the rights of women are now being increasingly defended. However, the court has been branded as macho and conservative by feminist groups. Recently, it ruled that 'at work, an isolated and spontaneous smack on the behind does not constitute sexual harassment,' (although since September the High Court apparently changed their mind). On another occasion they ruled that a woman could not have been raped as she 'was wearing tight jeans.'

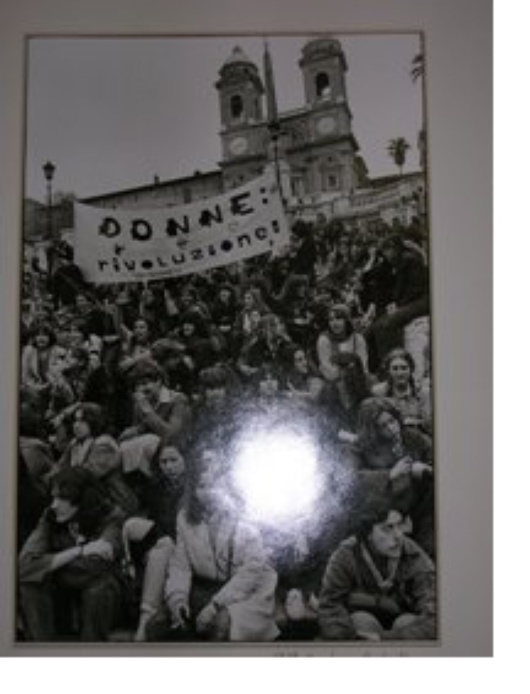

Home, bloody home

The women of Rome first demanded equality from Via Pompeo Magno during the sixties and seventies. Situated between the Vatican and the Piazza della Libertà, it led to the founding of the Centro Femminista Separatista in 1983. Today, it is better known as the International Women’s Centre (Casa Internazionale delle Donne), a not-for-profit organisation which encompasses over 40 feminist associations. 'When the movement began, they would send male journalists - but we asked for women correspondents instead,' remembers Edda Billi, one of the founders.

The main feminist concern is combating violence towards women. 'I prefer to call it sexist violence, rather than sexual. The word ‘sexual’ is too beautiful to be associated with violence,' says Edda Billi, with a hint of a smile. It is November 25, International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. Women clamour together in Rome's Piazza di Largo Argentina, demanding a stop to the violence. During the demonstration they chant feminist slogans, give speeches and wave placards bearing controversial phrases such as 'home, bloody home' or 'the murderer has the keys to my house.' However, at the height of the demonstration at 1pm, there are just 200 women and almost no men. Neither are there any young women, either at the demonstration or at the meeting taking place during the afternoon.

The main feminist concern is combating violence towards women. 'I prefer to call it sexist violence, rather than sexual. The word ‘sexual’ is too beautiful to be associated with violence,' says Edda Billi, with a hint of a smile. It is November 25, International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. Women clamour together in Rome's Piazza di Largo Argentina, demanding a stop to the violence. During the demonstration they chant feminist slogans, give speeches and wave placards bearing controversial phrases such as 'home, bloody home' or 'the murderer has the keys to my house.' However, at the height of the demonstration at 1pm, there are just 200 women and almost no men. Neither are there any young women, either at the demonstration or at the meeting taking place during the afternoon.

Man-made laws

In Rome, the small number of women involved in politics is shameful. Of the 17 members of the local government, only five are women. In the local council, parties such as National Alliance or Forza Italia (the second and third political parties in the city) do not have any women representatives.

At a national level, only two of the 18 ministries are headed by women in Prodi’s government. Barbara Pollastrini, Italian Minister for Equality, has pushed what appears to be a lacklustre new law protecting women. Compared to other European democracies, Italian women are increasingly 'isolated' in Europe. Countries such as Germany, Latvia or Finland, headed by charismatic women such as Angela Merkel and Tarja Halonen Vaira Vike-Freiberga, are much more egalitarian in this sense. In France, Ségolène Royal, a candidate in the next presidential elections, has announced that the first law which she would pass would be to combat violence against women.

In fact, many Italian women see Spain as the best example. Irene Giacobbe, from Italian NGO Power and Gender, jokes: 'Would you lend us Zapatero for a few months?' The egalitarian policies of the Spanish socialist have been well received by Rome's feminists. They praise the policies which have established equal numbers of male and female ministers, a new law outlawing violence towards women, and a proposed law guaranteeing equality between men and women.

In fact, many Italian women see Spain as the best example. Irene Giacobbe, from Italian NGO Power and Gender, jokes: 'Would you lend us Zapatero for a few months?' The egalitarian policies of the Spanish socialist have been well received by Rome's feminists. They praise the policies which have established equal numbers of male and female ministers, a new law outlawing violence towards women, and a proposed law guaranteeing equality between men and women.

The myth of the 'mamma'

Opinions are divided between Rome's society and those who live within it. Alice, an Australian teacher of English who has lived in Rome for a year and a half, asserts that 'Australian society is a lot more macho than in Rome, thanks to schools over there which are specifically for girls or boys only.' However, Edda Billi believes the opposite and refutes the myth which attributes all the power inside the home to the 'mamma.' 'The one who has control within the house is the television, the all-powerful ruler of contemporary society,' she explains. The programme 'La Pupa e il Secchione' (Beauty and the Geek) is a clear example. The main premise of the programme: a 'very intelligent' man tries to impart his knowledge to a beautiful woman in exchange for her trading on the secrets of her beauty to teach him how to look good. 'Uomini e Donne' is another example of the Italian television's machismo: men and women (often scantily clad) pretend to want to date each other.

The presence of the Vatican and its macho vision of the family unit plays a factor in this. The Casa Internazionale delle Donne is in the Trastevere neighbourhood, 'as close to the Vatican as possible, so as to annoy them,' jokes another activist, who does not want to be identified. The feminists summarise the situation in which the women of Rome live: 'the Vatican’s line keeps women in the home and reinforces the traditional papal view of women as subordinates, with our society acting as an accomplice with their silence.'

The presence of the Vatican and its macho vision of the family unit plays a factor in this. The Casa Internazionale delle Donne is in the Trastevere neighbourhood, 'as close to the Vatican as possible, so as to annoy them,' jokes another activist, who does not want to be identified. The feminists summarise the situation in which the women of Rome live: 'the Vatican’s line keeps women in the home and reinforces the traditional papal view of women as subordinates, with our society acting as an accomplice with their silence.'

(Photos: FGA)

Translated from Feminismo: la mamma morta