Feminism in France: the Rose Revolution

Published on

Translation by:

John Smith

John Smith

May 1968 was a turning point in world history, but it was also a rupture for women's history. Feminists of yesterday and today tell us about their war

Revolt pushing against patriarchal society, fields of misogyny blown in a society tightly fastened by the strings of a political and cultural straitjacket. May 1968 was a period which belonged both to lovely mothers, and to the French writer and philosopher Simone de Beauvoir's ideas; all devoured by the dissenting gap, cracking the battle flag of women's liberation and emancipation.

Abortion, contraception, parity and equality of the sexes; these issues are all familiar to us. However, we can't forget that it hasn't always been this way. 'Girl Power', the same slogan for which a certain UK pop group staked a claim, would never have had so many followers without the work of fierce predecessors.

Women's liberation movement

'More has been done for women in the last forty years than in two millions years of history'

There's a reason for all of this. After all, as Antoinette Fouque says, 'More has been done for women in the last forty years than in two millions years of history.' Fouque is a psychoanalyst and political scientist, former MEP and luminary of the 'women's liberation movement' ('Mouvement de Libération des Femmes', MLF), the monumental women's group created in 1968. What did it mean to be a feminist during the sixties and seventies? What were these militant feminists’ expectations and demands for their own living conditions?

The term 'liberation' was on everybody's lips, certainly those of women. Françoise Picq has a doctorate in political science, and is an assistant-professor ('maître de conférences') at the University of Paris IX-Dauphine. She was one of the first militants in the MLF in 1970. Picq is nostalgic about a time in history when 'the context of the moment was explosive. It was difficult being a woman in a society where we only existed as wives, mothers or daughters.'

After the events of 1968, the idea of women dominated by 'paternal power' had exploded by 1970. Feminists rejected being trapped in domestic slavery, and MLF militants were taking claim. In their

hearts, a revolution of morals and mentalities wasn't necessary; it was incontrovertible. Later, the women's association 'Choisir La Cause des Femmes' ('An association to defend, promote and spread women's rights’), was founded in 1971 by Simone de Beauvoir and lawyer Gisèle Halimi. The French movement for family planning was founded in 1956. It enabled women to make and choose their own destinies, amongst themselves.

Voluntary intervention of pregnancy: the warhorse

While the right to contraception was obtained in 1967, other claims were still scrambling to be heard. The pell-mell included the right to work, equality of wages, parity and the end of a system completely dominated by men. French politician Simone Veil helped legalise abortion in 1975 with the 'Veil Law' (‘Loi Veil’). Abortion was a crucial question in the feminist war, and it was also MLF's warhorse. According to French feminist and historian Bibia Pavard, 'Action was determined by women's right to decide, which was finally being recognised.' Women reclaimed their bodies and their sexuality; they accepted or rejected maternity according to their own fecundity.

While the right to contraception was obtained in 1967, other claims were still scrambling to be heard. The pell-mell included the right to work, equality of wages, parity and the end of a system completely dominated by men. French politician Simone Veil helped legalise abortion in 1975 with the 'Veil Law' (‘Loi Veil’). Abortion was a crucial question in the feminist war, and it was also MLF's warhorse. According to French feminist and historian Bibia Pavard, 'Action was determined by women's right to decide, which was finally being recognised.' Women reclaimed their bodies and their sexuality; they accepted or rejected maternity according to their own fecundity.

'All too often, women have no knowledge of their own rights'

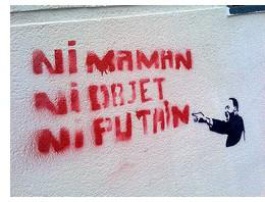

Almost forty years later, what is left of feminism and of the events of 1968? What has become of the fight started by those vigilant women? Today, associations are numerous and they continue to make themselves heard in the defence of women's rights. 'The work accomplished by the women of '68 was considerable, but there's still a lot to be done,' emphasises Sihem Habchi, the current president of the feminist association 'Ni Putes Ni Soumises' ('Neither Whores Nor Submissives'), a group set up for the daughters of immigrants. 'The successes of 1968 came to a stop in immigrant neighbourhoods, like in the suburbs of Paris. Here, all too often, women have no knowledge of their own rights.' They didn't emancipate themselves like white women did in 1968.

The same thing happened for the militants of the 'Femmes Solidaires' association. They say it is urgent to provoke younger generations, bring them into the debate and fight against regressions. Yesterday's reforms can be lost tomorrow. Just as with 'Mix-Cité', a movement for the equality of the sexes founded in 1997, we war against the mentality of sexism, in which men are imperatively implicated. Certainly, things have changed for us, our societies have profoundly evolved. The face of our existence has improved since our mothers' time, but defending our rights as women remains a reality.

Translated from Féminisme : la révolution rose