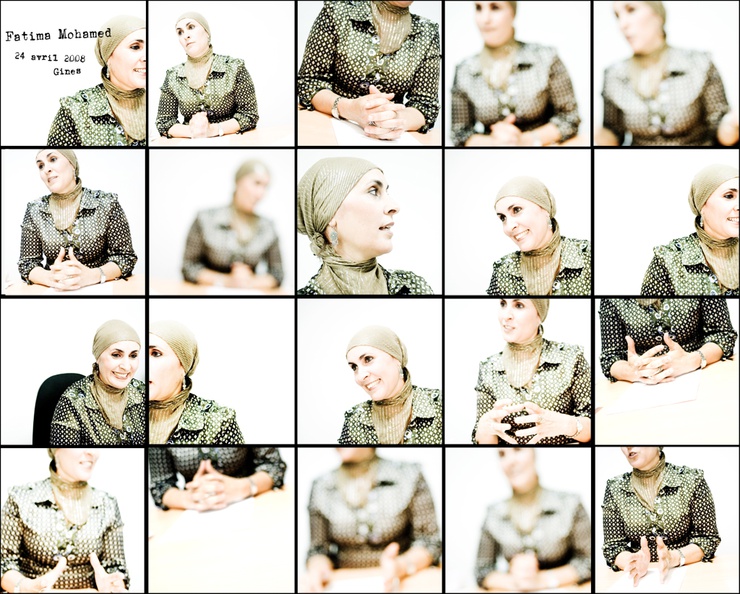

Fatima Mohamed Kaddur: a muslim in the Spanish people's party

Published on

Translation by:

leila reid

leila reid

The 43-year-old is a practising Muslim from Melilla who works for the opposition in Gines, Seville. We talk about why she won't force her daughters to wear the headscarf, which she doesn't see as a barrier and has publicly taken a stance on against her party leader, Mariano Rajoy

Gines is a municipality of the province of Seville with little more than twelve thousand inhabitants. At the end of April it’s already over thirty degrees. I meet Fatima Mohamed Kaddur in front of the headquarters of the Guardia Civil (military police) where she arrives with a friend, Maria. Fatima has a friendly air, and takes us to the head office of the Gines partido popular (People’s Party). On the walls Spanish and Andalucian flags hang alongside a portrait of Mariano Rajoy, the party chief and Spain's opposition leader.

Gines is a municipality of the province of Seville with little more than twelve thousand inhabitants. At the end of April it’s already over thirty degrees. I meet Fatima Mohamed Kaddur in front of the headquarters of the Guardia Civil (military police) where she arrives with a friend, Maria. Fatima has a friendly air, and takes us to the head office of the Gines partido popular (People’s Party). On the walls Spanish and Andalucian flags hang alongside a portrait of Mariano Rajoy, the party chief and Spain's opposition leader.

Fatima, 43, comes from Melilla, an autonomous city on the ‘Moroccan’ coast of North Africa that came under the Spanish crown in 1497, during the Reconquista of the catholic kings. It seems strange to think of a Muslim in a party like the Spanish PP; a right of centre party with catholic leanings. This, of course, is the first thing one thinks to ask her about, but I don’t get the chance to pose the question.

'When you hear it said that the PP is a racist party is simply wrong'

‘I know many people are surprised: a Muslim woman, who wears the headscarf, in the PP,' she says, telling me about herself in a well-versed manner. 'In my party I feel integrated, respected and wanted. When you hear it said that the PP is a racist party is simply wrong. And if it fights over immigration, it does it so that those who come here have a contract and live like everyone else.’ Melilla, which has a 45% Muslim population, also has a 'Spanish nationalist' rightist tradition: the Moroccan government has demonstrated the will to annex it several times, along with Ceuta and the small islands. But neither Spain, nor less the two cities, have ever considered the offer. Because they feel Spanish.

Fatima, already in her second term in office, is a local councillor and provincial delegate for immigration. Why did she enter politics? ‘I began over fifteen years’ ago because, as I said, I’m from Melilla; a small, poor, Muslim part of Melilla that politicians had forgotten. I wasn’t a settled person, and I had some problems with my father and my family. I could see that the area needed drinking water, sewers, and roads…’ The city was governed by the PSOE (prime minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero’s Spanish socialist workers’ party). Fatima naturally looked toward the opposition. ‘One evening I was walking with a friend and we passed the offices of the people’s party. I went in, and there was a guy I knew there. I said to him 'I’m not in any political party, but I’d like to work for the opposition.' He asked me if I’d like to join, I did, and I began to work with the PP.’

She began working on local issues in Melilla, and continued even after she moved to Seville with her husband. She is regional president of Afammer (rural women and families association) which focuses on training and employment opportunities and prevention of gender violence. She also runs a course at the Seville telecommunications university on ‘Religion and Society’.

Flamenco in a headscarf

In February 2008 Rajoy proposed some restrictions to the wearing of the headscarf in Spain, largely in schools as is has been implemented in France. Fatima immediately and publically took the opposite stance to Rajoy. She now attributes the ensuing clamour to pre-election exploitation by the media. 'In any case, my party supported me. When Rajoy made that statement I said 'you don’t touch the headscarf'. The party stood with me and precisely for this reason I don’t see the headscarf a barrier.'

‘The headscarf is integration, and that’s what I work for’

What does the headscarf represent, then? ‘The headscarf is integration, and that’s what I work for. I don’t feel discriminated against. For example I go Rocío (a Spanish catholic pilgrimage with a strong tradition in Andalucía) with the women I work with, in flamenco dress and a headscarf. This represents full integration and is an example, helping fight racism against immigrants’. She believes in multiculturalism because she’s lived it: ‘in Melilla there are mixed classes and children are used to it from a very young age. I believe in, and work for, full integration.’

Fatima was married to a Sevillian for twenty-two years – she’s now separated – and has three children; two girls, aged 21 and 13, and a boy of 19. Do her daughters wear the headscarf? ‘I follow my family’s example. My father’s over eighty and he didn’t make me wear the headscarf. My mother, on the other hand, always wore it. I’m a practicing Muslim but when I was single I didn’t, I began after I was married, and I’d never make my daughters wear it.’ Her elder daughter tells her she’ll start wearing the headscarf when she finishes university. ‘When they say that Muslims force their daughters to wear the headscarf it’s nonsense. People confuse chauvinism with Islam and with religion.’

Coffee with Sarkozy

Part of Kaddur's family lives in France and the rule’s the same: it’s an individual choice. She’d like to go to Paris and ‘test’ the politics of the French president. ‘I’d like to have a talk with him about immigration and religion’. And essentially her position is clear: when I ask her about the mosque that will be built in Seville in 2010, she expresses some doubts but finishes saying ‘anyway, I’m a politician. I don’t concern myself with religious questions’.

Part of Kaddur's family lives in France and the rule’s the same: it’s an individual choice. She’d like to go to Paris and ‘test’ the politics of the French president. ‘I’d like to have a talk with him about immigration and religion’. And essentially her position is clear: when I ask her about the mosque that will be built in Seville in 2010, she expresses some doubts but finishes saying ‘anyway, I’m a politician. I don’t concern myself with religious questions’.

After the interview we go to a bar for coffee. Fatima chats to the people there, greeting and smiling. We smoke a cigarette – Spanish law allows exemptions indoors – and we talk about Europe. For her it’s a place where you can do a lot, but where you also have to abide by its history. ‘For the EU to work, it has to be a union of countries, but without foundations a house won’t stand’. Everyone fights for himself ‘so that the union is strong’.

Many thanks to Bénedicte Salzes and José R. de Arellano

First published on cafebabel.com on 6 June 2008

Translated from Fátima Mohamed Kaddur: «Il velo è integrazione»