Fatih Akın breaks Armenia's taboo with The Cut

Published on

Translation by:

Kath Burns

Kath Burns

The Cut is about to released in German cinemas and, despite receiving death threats from Turkish ultranationalists, its director remains enthusiastic. But what are Fatih Akin's real reasons for tackling the Armenian genocide?

This particular anniversary is not a cause for celebration, although commemorative events will take place. With the centenary of the Armenian genocide approaching, The Cut – Fatih Akin's latest film — will finally break the taboo that surrounds it, but it has provoked anger and death threats from Turkish far-right groups. Forty-one year old Akin, who is German-Turkish and the son of immigrants, grew up in Altona, a borough in Hamburg. He became more widely known with films such as Solino (2002), The Edge of Heaven (2007) and Soul Kitchen (2009).

Cinema and the Armenian genocide

Fatih Akin initially planned to make a film about Armenian journalist Hrant Dink, who was assassinated in broad daylight by a nationalist in Istanbul in 2007, outside the offices of Turkish-Armenian newspaper Agos, which he had co-founded. However, Akin reconsidered the project after political issues surrounded the casting of his protagonist. While the director wanted an actor of Turkish origin to play the lead role, all other actors who were already on board at that point refused to continue, fearing that extremists would retaliate. Akin was forced to abandon the project and begin another one.

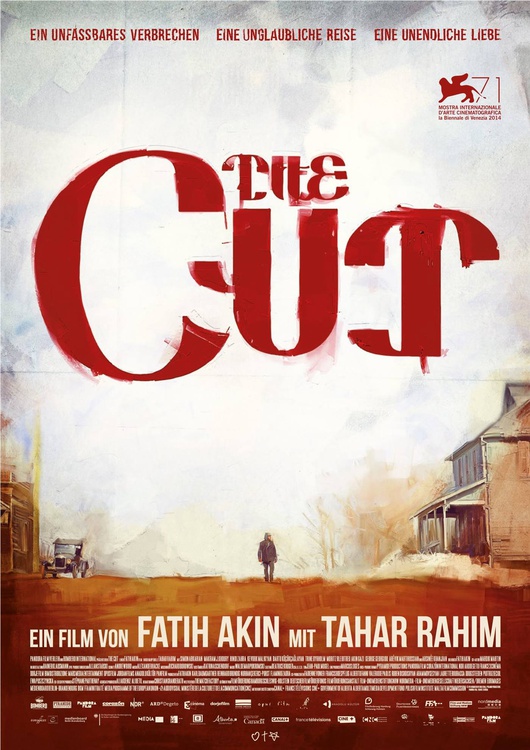

Akin spent seven years preparing for The Cut, and he is one of the first film directors of Turkish origin to use cinema to tackle a subject — the Armenian genocide — which not only remains a sensitive political taboo in Turkey, but which the Turkish state also officially disputes. More broadly, the film explores themes that are frequently found in Akin's work: love, displacement and death. The Cut tells the story of a young father, Nazaret Manoogian, who is torn from his family by Turkish policemen and manages to survive the first year of the First World War. Nazaret must then begin his search for his twin daughters, and this journey to find his missing family takes him to Syria, Cuba and the United States.

Although issues surrounding Armenia and the Armenian genocide are rarely touched upon in cinema, Akin highlighted them by premiering his film at this year's Venice Film Festival. The Cut (2014) takes its place alongside films such as Ravished Armenia (1919), Nahapet (1977), Forty Days of Musa Dagh (1982), Mayrig (1991), Ararat (2002) and Le Voyage en Arménie (2006). The next addition to this list will be Robert Guédiguian's upcoming feature-length film, Une histoire de fou, which is expected for release in spring 2015.

Official trailer for The Cut, with French actor Tahar Rahim.

Akin chose to study the Armenian genocide in more detail because the subject, for him, is "taboo, forbidden and dangerous". This film is a chance for him to discuss it and to pursue both his desire to know more and his quest for the truth. Alongside their death threats, Turkish ultranationalists have warned Akin that his film will never be shown in any cinemas in Turkey. According to them, the film is "the first in a series of initiatives aimed at pushing Turkey to accept the lie of the Armenian genocide."

From a strictly cinematic point of view, the film has been criticized for apparent shortcomings which leave it in an uncomfortable no-man's-land where it is impossible for the viewer to judge whether they are watching a genre film or a political and historical drama. Akin responds to that criticism adroitly by saying that he does not know how to define genocide or the appropriate genre for dealing with it — or, for that matter, whether film is even capable of handling such a subject. What he's certain of, however, is that Turkey is "ready for this film".

Akin's "biggest dream"

Akin has found support from Turkey's journalists, thanks to their political leanings, who have confirmed that "this film could unequivocally be shown in Turkey. In fact, it has to be shown." Overjoyed at the response, Akin has never hidden the fact that releasing his film in Turkish cinemas was "his biggest dream". According to Simon Abkarian, who plays Krikor in The Cut, this is the film that Armenians have long been waiting for. However, the intentions behind the film are much wider and, most importantly, are rooted in reconciliation. Akin believes that both Turkish and Armenian viewers will find themselves able to identify with the protagonist, and what works for an individual can also work for a community. The Cut aims to contribute towards overcoming a psychological trauma, and does not simply teach or discipline its viewer. Above all, this film invites us to identify with its characters and share their emotions; it highlights a trauma and establishes a dialogue that is free from hatred, while pursuing reconciliation. Civil society representatives working together to recognise and remember the genocide is all the more important since entire generations of Turkish people have been taught by their state that the genocide committed by the Ottoman Empire is a lie, and that Armenians are the nation's enemy.

Extract from an interview with Fatih Akın (3rd September 2014)

The political dimension

Although The Cut chooses not to explore the question of German responsibility in the face of the Armenian genocide, its director has not forgotten the Germany of yesteryear — the Germany that was a strategic ally to the Ottoman Empire, against the Triple Entente alliance. He says that Germany "stayed silent, and let it happen." To this very day, the German government does not refer to a "genocide". The Bundestag resolved in 2005 to describe the Armenians as being victims of a "massacre".

President Erdogan's statement in April this year, on the eve of the 99th anniversary of the Armenian genocide, was welcomed by some observers as a "symbolic step on the road towards recognition". His "condolences" were expressed to the "grandchildren of Armenian people killed in 1915". However, reading between the lines reveals that Erdogan maintains a stance of denial. Franck Papazian, from the CCAF (Co-ordination Council of Armenian Organisations of France), argues that the Turkish President's statement was all about "media impact", since he makes no reference to "apologies" or to a "genocide". Instead, the statement perpetuates the theory that massacres were committed by both the Turks and the Armenians against the backdrop of the First World War, despite the fact that most historians have reached a different conclusion. French President François Hollande believes that Erdogan's statement promotes a "message that must be heard but is still not enough."

President Erdogan's statement in April this year, on the eve of the 99th anniversary of the Armenian genocide, was welcomed by some observers as a "symbolic step on the road towards recognition". His "condolences" were expressed to the "grandchildren of Armenian people killed in 1915". However, reading between the lines reveals that Erdogan maintains a stance of denial. Franck Papazian, from the CCAF (Co-ordination Council of Armenian Organisations of France), argues that the Turkish President's statement was all about "media impact", since he makes no reference to "apologies" or to a "genocide". Instead, the statement perpetuates the theory that massacres were committed by both the Turks and the Armenians against the backdrop of the First World War, despite the fact that most historians have reached a different conclusion. French President François Hollande believes that Erdogan's statement promotes a "message that must be heard but is still not enough."

Would it be wrong to plead for recognition in order to achieve reconciliation? Can the pressure exerted by two peoples — the pressure of everyday social bonds — force the political establishment to recognize the genocide, or must that recognition stem from politicians in order to pave the way for reconciliation within society? Questions that are posed as "one or the other" or as black and white often fail to reflect the complexity of social realities and their mutual dependence.

Whatever happens, it is worth wondering whether the Turkish authorities recognizing the genocide might potentially transform the region in geopolitical and human terms. It could prompt Turkey, Armenia and possibly even neighbouring states such as Azerbaijan to redefine themselves nationally. As Franck Papazian points out, if Turkey were to officially recognize the genocide as part of the centenary commemorations, it would be "a powerful gesture which would allow Turkey to rediscover its stature and become more European."

Fatih Akin's The Cut will be released in cinemas in the UK and France in early 2015

Translated from The Cut : Fatih Akın tranche le tabou arménien