Exiled from Iran: the thirst for liberty

Published on

Translation by:

joshua craze

joshua craze

The Iranian community are well integrated in Europe, and they remain unanimous in their desire that Iran respects human rights

Berlin, Wilmersdorf. In this chic area of the German capital, an Iranian store has bread, rice, pistachios, dates and fresh spices on display. Hidden amongst the fruit you can also find Iranian music and books. People come here to buy a taste of their homeland, to talk and gossip. In this small store, everybody knows everybody.

A few streets further on, in a small Iranian bookshop, Abbas Maroufi, one of the best known Iranian writers, is seated at a table next to a telephone. An affable man, he gives me a nod as I enter. In Iran, his magazine, Gardoun (the vault of the sky), was an important voice of criticism against the government until it was banned in 1991. However, his articles criticising the system of power in Iran attracted the anger of the authorities. Maroufi was sent to prison on several occasions. After his last arrest in 1996, he fled Iran; he is currently in exile in Germany. According to Maroufi, it is unacceptable that Tehran can acquire nuclear weapons while not respecting human rights inside of Iran. Some of his compatriots agree with him. Last April, a group of twenty Iranians chained themselves to the Iranian embassy in Berlin, chanting, “No nuclear power for Iran.”

Close to 120,000 Iranians live in Germany. Many of them left Iran after the revolution in 1979. However, they do not live a cloistered existence: there is neither an Iranian enclave, nor an Iranian area of Berlin. This also applies to the rest of Europe – where the Iranian community seems to be perfectly integrated. The principle reason for this thriving existence is the high degree of heterogeneity within the Iranian community. There are a number of cultural organisations, and there are political groups, both supporters and opponents of the regime. According to the Iranians in exile, there are not just doctors, engineers and businessmen in exile, but also artists, all thriving within a community that looks out and speaks to the other communities in Europe.

Abbas Maroufi is a part of this last group. He explains that even if he is giving a precise opinion about the political situation in Iran, he is above all a writer. In his magazine, there is a huge variety of work: well known Iranian poets jostle with comic book authors; Rumi has to fight for space with comic books like Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi.

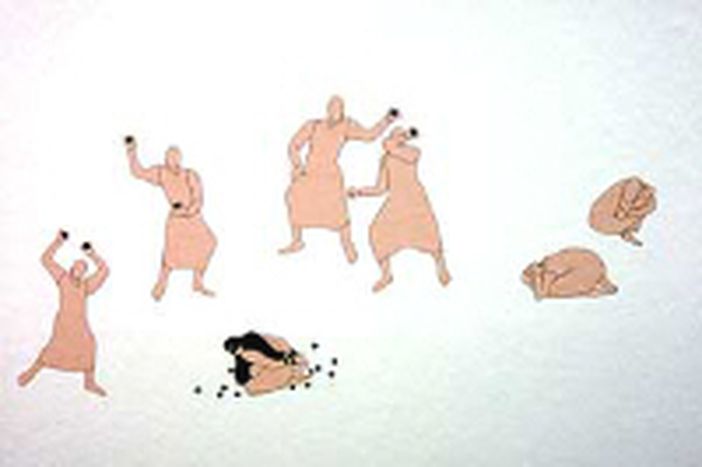

Persepolis tells the tale of Satraipi: a young girl suffering under an oppressive regime in Iran who is sent to Austria at the age of 14 to escape the Iran-Iraq war. The heroine of the book goes home at the end of the war, but leaves Iran definitively at the age of 18: her thirst for liberty too great to allow her to stay at home. Today, the illustrations of this Paris-based artist are well known throughout the world. Marjane Satrapi illustrates for Libération in Paris and the New York Times. Her compatriot, the Frankfurt based conceptual artist Parastou Forouhar, has also been a victim of human rights abuses in Iran. Her parents, opponents of the regime, were assassinated in 1998. In her work, Forouhar underlines the importance of fighting for liberty in her country; struggling for the rights of women.

The enemy Ahmadinejad

The new president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, has defied the international community with his nuclear program and calls for the destruction of Israel. He remains the spectre that haunts most Iranians in exile. “And to think this pathetic man represents our beautiful country” Forouhar says indignantly. Bahman Nirumand, a renowned writer, formulates this is a more elegant manner, but the message remains the same. After Ahmadinejad became President, he wrote in the German politics magazine Cicero, that Ahmadinejad would be a head of state with “politically untested, completely radical ideas far removed from reality.” Abolhassan Bani Sadr, the first president of the Islamic Republic, who is in exile in France, is more extensive in his critique. In a televised interview, he gave “nine reasons to say that the presidential elections do not bode well.”

Maryam Namezie uses information in the public domain to support the struggle for human rights. On her blog, she denounces the arrests of opposition members and journalists in Iraq. Nevertheless, she categorically refuses the idea of a second military intervention. We must not have a “second Iraq,” she writes. She does not hesitate to address herself directly to the American secretary of state, Donald Rumsfeld: “If someone can bring liberty, equality and prosperity to Iran, it is certainly not you. It can only come about through a revolutionary movement in Iran that fights for the fall of the Islamic Republic.” The German-Iranian journalist Navid Kermani, in an article for the Süddeutsche Zeitung, has also signalled the risks of an attack on Iran: he claims it would simply reinforce the regime of the Mullahs. At a protest during the Easter holidays, Bahman Nirumand was explicit. “No new war in the Gulf, no war against Iran.”

The situation remains tense. Ahmadinejad has announced that he will go to Germany in June for the World Cup, which sees the participation of the Iranian national team. His presence is undesirable in the eyes of both the Jewish and the Iranian communities in Berlin. Mahmoud Rafi clarifies the situation: “If Ahmadinejad comes here, he will face a wave of massive protests.”

Translated from Exil-Iraner: Für Freiheit, gegen Krieg