Europe's suicide tourism

Published on

Translation by:

Helen Bowden

Helen Bowden

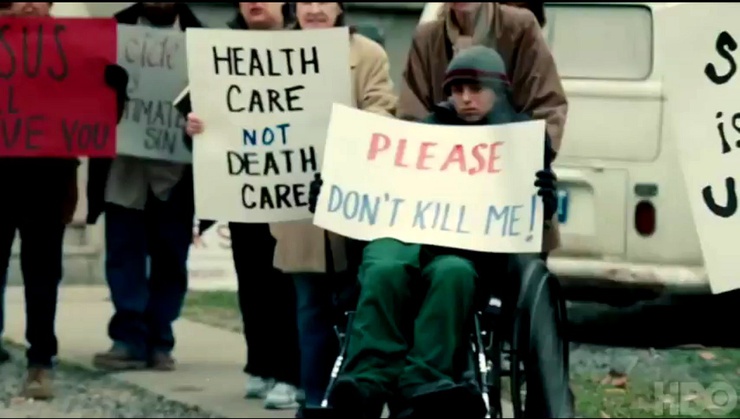

Al Pacino put a damper on the atmosphere at the 50th Monte-Carlo television festival. In 'You don't know Jack' he interprets a doctor who is convicted several times for his practice of euthanasia.

Soon to be released in France, Barry Levinson's film threatens to revive a debate which divides Europe, beginning wih the Netherlands, where the supporters of the 'Out of Free Will' initiative are campaigning for a 'right to die' for everyone over 70

As they received their suicide pill on 8 April, the Dutch members of parliament must have felt a touch of anxiety. There was no cause for alarm however, no subliminal message in the deadly candy, a gift from the Out of Free Will activists. Nothing but the sweetness of 'the right to die.'

Taking leave

From Frits Bolkestein (originator of the famous European directive) to Dick Schwaab (neurobiologist), fifteen celebrities claim the right to decide for themselves whether life is still worth living with Out of Free Will. Once past the age of seventy, they argue, we should be able to take our leave. Active euthanasia - the injection of a lethal substance to hasten the final moments of someone terminally ill - has been legal in the Netherlands since 2002. The petition is now calling upon members of parliament to decriminalise assisted suicide and assign specialists to implement its practice.

First presented on the internet in February, Out of Free Will's petition has collected almost 117, 000 signatures and resulted in the submission of a public bill to the assembly on 18 May 2010. With the christian conservatives in the majority however, there is little chance of it passing: euthanasia remains a controversial topic.

'Suicide tourism' : terminus Zurich

Until now, Dutch grandpas have still had to travel a long way to 'depart of their own free will'. Although Luxembourg and Belgium also permit euthanasia, it is on the basis of a long-term patient-doctor relationship: a non-resident cannot benefit. In France or Great Britain, the law tolerates withholding treatment only in cases where the patient is terminally ill. In Greece and Poland the matter is not open for discussion. For those who choose to die, all roads lead to Switzerland.

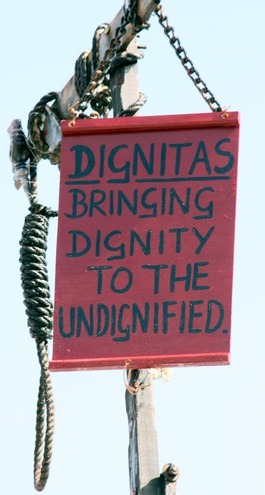

In Zurich, the organisation Dignitasstudies every 'genuine' application. Those who manage to get an appointment meet its founder, Ludwig Minelli, who has to give his agreement before the applicant can see a doctor. It is the latter who carries out the final act: a prescription of sodium pentobarbital, a powerful barbiturate. At this stage, only a third of visitors confirm their desire to have done with it all. Out of 1, 100 individuals 'escorted' since 1998, 935 are alleged to be foreigners the local authorities denounce what they call 'suicide tourism.' Hubert Sapin, the delegate in Lyon for the association for the right to die in dignity ('Association pour le droit à mourir dans la dignité', ADMD) confirms having received 'numerous requests of this kind.' In an interview with the French newspaper Le Monde in 2008, Ludwig Minelli retorted: 'I consider that assisted suicide is a human right. Besides, do we criticise the banking tourism in Switzerland, which allows European citizens not to pay their taxes?'

The examples keep coming: French actress Maïa Simon and English conductor Edward Downes have both been to knock on the door at Dignitas. Just like Craig Ewert, a retired American living in London, whose final journey is recounted by the director John Zaritsky in the 2007 film The Suicide Tourist.

Socrates vs. Brave New World

Dignitas has had to move from Zurich's town centre following complaints from neighbours. Thanks to the support of 240 of its members, the organisation has bought itself a building in the industrial area of Pfäffikon for the modest sum of 840, 000 Swiss francs. 'Dignitas asks 6, 000 euros for its services. Not everyone can afford it,' deplores Hubert Sapin. Soraya Wernli, Minelli's former secretary, accuses Dignitas of 'making money off the sick.' The controversy took a macabre turn on 28 April 2010, when dozens of funerary urns were found in Zurich's lake. According to the police, they come from the crematorium used by Dignitas. A complaint has been filed 'against persons unknown,' and the organisation no longer responds to journalists' questions.

Dignitas has had to move from Zurich's town centre following complaints from neighbours. Thanks to the support of 240 of its members, the organisation has bought itself a building in the industrial area of Pfäffikon for the modest sum of 840, 000 Swiss francs. 'Dignitas asks 6, 000 euros for its services. Not everyone can afford it,' deplores Hubert Sapin. Soraya Wernli, Minelli's former secretary, accuses Dignitas of 'making money off the sick.' The controversy took a macabre turn on 28 April 2010, when dozens of funerary urns were found in Zurich's lake. According to the police, they come from the crematorium used by Dignitas. A complaint has been filed 'against persons unknown,' and the organisation no longer responds to journalists' questions.

One of a kind, Dignitas serves alternately as example and bugbear. The idea that death can be planned evokes uneasiness. 'When I became a member of ADMD in 1988, I didn't tell anyone at first, in case people thought I was morbid,' recalls Hubert Sapin. Today, the debate is beginning to interest young people. Daniel James, a 23-year-old English rugby player paralysed after an accident in the scrum, appealed to Dignitas in 2008. More and more under-30s, made aware of the issue by cases like his, are preparing their 'pre-emptive instructions,' a document allowing them to express their wishes concerning the action to be taken as life draws to a close. ADMD's 'youth commission,' an organisation claiming 48, 000 members, will even have a stand at the Solidays festival in Paris at the end of June.

'When I became a member I didn't tell anyone at first, in case people thought I was morbid'

Serenity and control at the moment of dying, or the nightmare of a society numbed by technical advances? On the one hand, we refer to the death of Socrates, on the other, we shudder as we recall Brave New World, we wield the spectre of eugenics and wail at the abuse of power. In The Suicide Tourist, the character of Betty Coumbias makes an attempt at a response: 'I'm quite well, but that is not the question. If you want to finish your life, well, it's your life!' In an era where science is setting its sights on immortality, choosing death might appear to be the ultimate form of liberty.

Images: ©frozi/ Flickr video and screenshot You Don't Know Jack, trailer by HBO; ©musth14/ Youtube; Dignitas ©Victius/ Flickr

Translated from Le suicide assisté, luxe ultime cher aux Hollandais