Europe’s linguistic plurality: gem or stumbling stone?

Published on

Translation by:

fiona wollensack

fiona wollensack

Irish is set to become the 21st official language of the EU in 2007. Are there boundaries to the number of idioms the European Union can cope with?

The EU runs the world’s largest translation service, employing nearly 4,000 translators and interpreters. In addition to the roughly 100,000 pages of treaties and laws which need to be translated into the 20 official languages, interpreters for the present 380 different languages combinations are required. Europe has to pay for its rich linguistic tapestry – about 800 million euros per annum. But money is not the only problem. It is the efficiency problems which are increasingly bringing things to a grinding halt. It has had to be agreed that due to the administrative complexities and resource requirements, Maltese cannot be one of the official languages.

So why go to all this trouble if resources are so stretched? After all, the United Nations has nearly eight times as many members, but just a quarter the number of languages. The answer is not to be found in the political vanities of the member states: the quaint linguistic chaos has a clear legal motive. As opposed to “classical” international law, national parliaments cannot position themselves between their citizens and Brussels as “official translators” of the law. The direct and immediate effects of Community law necessitates the translation process. This provides the citizens of the EU with the advantage of being able to access all European law in 20 languages with a simple mouse-click!

The boundaries of linguistic plurality

Article 21 of the Treaty of Rome allows the citizens of the EU to approach all EU institutions in any one of its official languages, which are then bound to answer in the same language. This impressive expression of the European regard for linguistic plurality is not self-evident. The founding of states – and the EU is a state-like entity – is usually accompanied by a homogenisation of the languages within its borders. Abbé Gregoire included some 30 languages and dialects in his treaty for France during the time of the Revolution because almost half of the 28 million “French” of the time could not converse in “French”. Had Europe followed the example set by its composite states, the continent would by now be well on its way to a sad linguistic monoculture.

But the European Community never wanted to become a super-state and linguistic plurality was, and remains, Europe’s motto. But where are the boundaries of this linguistic paradise? In actual fact, things are increasingly developing into a hierarchy of use for the 20 official languages. This flexibility has also been given the go-ahead by the European Court of Justice. The Kik ruling established that there is no constitutional principle governing the strict equality of the official languages. The numerous minority and religious languages of Europe spoken by some 50 million EU citizens lead a shadowy existence, mostly ignored in the corridors of European institutions – even if the Spanish regional languages (Catalan, Basque and Galician) were recently given the lesser status of “official usage”, rather than being acknowledged as full official languages.

One economic area but a multitude of languages

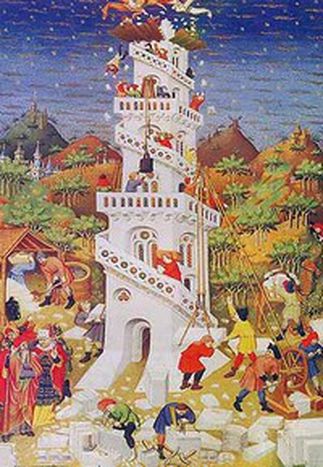

Mobility is six times higher in America than in the EU, where language barriers impede the free movement of goods and people. From the point of view of business there would, therefore, be two ideal scenarios: everyone speaks one language or everyone speaks every language. The first scenario, which would entail the establishment of a lingua franca, was never politically desirable or practically possible. Nonetheless, English has by now become that which Latin was for Europe in the Middle Ages.

The driving forces making English the dominant transnational language within Europe are however to be found outside of the European institutions. The official Europe, in particular the European Commission, are quite taken by the second scenario: as many citizens of Europe should speak as many languages as possible, at the very least two languages in addition to their mother tongue. This aim is at the heart of the new European Action Plan for Language Learning and Linguistic Diversity.

The language of democracy

A decade ago, in its notorious Maastricht ruling, the German Constitutional Court quietly questioned whether the European Union would ever be able to develop into a true democracy, with its lack of a shared open space and of a European discourse. Does European democracy need a European language? The answer is no. How else would the democracies of India or Switzerland be possible? What is lacking is a European press which deals with European issues for a European readership and audience. Multilingual initiatives such as café babel are what is called for, and not just in the name of linguistic plurality, but for the love of Europe.

Translated from Europas Sprachenbabel: Perle oder Stolperstein?