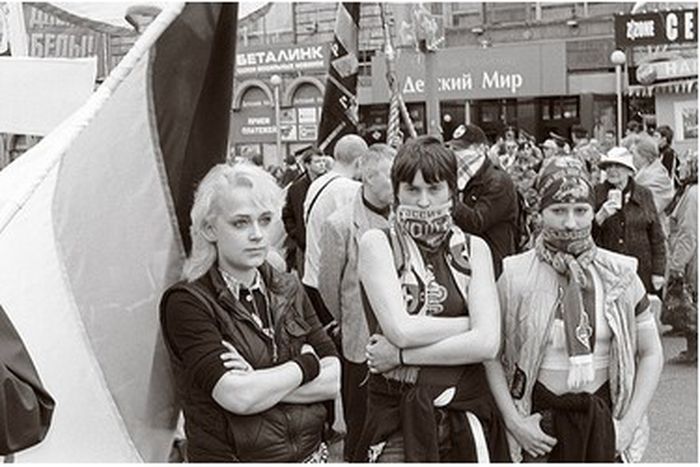

Europe's far-right youth: '10 years ago we were 'Nazi losers'. Now it’s ok to be a Nazi'

Published on

Translation by:

Aatish PattniTheir election scores confirm it; the extreme right parties have got the wind in their sails. A new generation of activists has arrived to take up the duties, and they have profoundly changed the way in which the extreme right does politics

They sell CDs of little girls who sing softly about white pride to a public of pre-adolescents, video games where it is essential to shoot all those who are dark-skinned, and t-shirts with cryptic slogans. They are British, Romanians, French and Swedes. They mistrust the various media and, instead, create their own press agencies to produce and broadcast their information. Gabriele Adinolfi, the co-founder of terza posizione ('third position', Italy) confirms that: 'Today, the only way of being fascist is by being pragmatic.'

The ‘right to centre right’ parties are in the process of change having been unrespectable for a long time. The EU has been looking to fight against acts of racism and xenophobes, and to bring legislation into line in member states on the matter of strengthening police co-operation. The extreme right has had a resurgence over the years in France, Austria and Italy and has had to face up to reactions from public opinion. The extreme right has therefore moved with the times.

The extreme right has had a resurgence over the years in France, Austria and Italy

They are now made up of a myriad of small groups, and when the dots are all joined up they form a ‘showcase’ political party. The extreme right have placed themselves into the mass media (via music, clothing and merchandising), and are now imposing themselves on the media-related networks across the EU. This strategy is paying off; the extreme right is the leading political party amongst 15-30 year olds in Holland, Austria and Czech Republic. Their influence is growing everywhere.

This strategy is called ‘metapolitics’; it’s the art of doing politics without it having the look of politics. In line with those who think like Guillaume Faye (nouvelle droite or 'new right' party in France), the extreme right is ‘surfing’ on being anti-politically correct, the loss of impetus by government parties in putting forward new venues on the outside of official circuits. Métapédia was created in 2007 by young Swedes based on the model of a well-known mass encyclopaedia; the Wikipedia moderators then gathered up the pages and excluded them.

This strategy is called ‘metapolitics’; it’s the art of doing politics without it having the look of politics. In line with those who think like Guillaume Faye (nouvelle droite or 'new right' party in France), the extreme right is ‘surfing’ on being anti-politically correct, the loss of impetus by government parties in putting forward new venues on the outside of official circuits. Métapédia was created in 2007 by young Swedes based on the model of a well-known mass encyclopaedia; the Wikipedia moderators then gathered up the pages and excluded them.

The extreme right is now in nine countries in the EU and their ambition is to ‘have an influence on political and philosophical debates and they way in which art and culture are presented’. Altermedia offers a platform for 17 different EU countries to different circles of influence with a right wing identity (from radical christians to anti-capitalist pagans), who want to challenge the challenge the traditional left wing supremacy in the domains of ideas and culture. It’s Denis Diderot who welcomes the visitor to Metapedia France, and the author and poet Mihai Eminescu who wrote Emperor and Proletarian, on Metapedia Romania.

Jacques Vassieux is the Rhône-Alpes regional advisor to the French FN Party ('national front'). He has taken charge of the national association observatoire et riposte internet ('internet observatory and riposte') from French far-right politician Jean Marie Le Pen, and created Nations Presse in 2008. The site gets 350, 000 hits a month and has 25 contributors; two of which are professional journalists. 'It is more than evident that we are treated badly on the internet, and on a daily basis too,'explains Vassieux. 'This is one of the reasons, essentially, why proceeded to create our site and this association. We can administer the antidote on a daily basis too.'

Jacques Vassieux is the Rhône-Alpes regional advisor to the French FN Party ('national front'). He has taken charge of the national association observatoire et riposte internet ('internet observatory and riposte') from French far-right politician Jean Marie Le Pen, and created Nations Presse in 2008. The site gets 350, 000 hits a month and has 25 contributors; two of which are professional journalists. 'It is more than evident that we are treated badly on the internet, and on a daily basis too,'explains Vassieux. 'This is one of the reasons, essentially, why proceeded to create our site and this association. We can administer the antidote on a daily basis too.'

Claudio Lazzaro is the author of the documentary Nazirock. 'The extreme right has made itself more straightforward,' he says. 'It takes what it needs and changes it in order to communicate without making it subtle.' Lazzaro advocates dialogue with the extreme right as long as this dialogue 'does not seek to justify their fascist ideas.' He also finds it alarming that 'fascism and neo-fascism are developing in parallel on two fronts, as if it’s about choosing ‘a priori’ (without prior knowledge) more than rational thought and reflection.'

Noua Dreapta ('new right') is spearheading the Romanian extreme right; they’re not registered as a party but present themselves as a ‘movement’, having been in existence since 2000. It’s a way of declining electoral confrontation in order to better place their sympathisers into the training which is being readied for them. The British national party (BNP) have swapped their Doc Martens for suits and ties, they distribute guides amongst their followers on how to speak properly, made space for women (in the party) in order tone down their image and have established the birth rate as one of their ‘call to arms’.

This new generation of young educated leaders have a perfect command of 21st century communication, and know their public well. Rock concerts have replaced granddad meets. Project Schoolyard is a series of compilations produced by the neo-nazi music label Panzerfaust Records; their eloquent slogan is ‘we don’t just entertain racist kids, we create them’.

‘We don’t just entertain racist kids, we create them’

The EU is struggling to keep up with the declarations of ‘good intentions’ and a real lack of involvement from the member states; the majority are ‘continuing to escape from control of their individual policies and practises at EU level’. The 2009 report on the situation of fundamental rights in the EU was panned. It has to be said that the extreme right’s electoral platform greatly interests the right wing of the government. When the right fail to visibly woo their voters, they don’t hesitate in taking the extreme right’s campaign themes. A few ‘identity’ rock concerts have closed national front and casa delle libertà (CDl, 'house of freeedom') campaign meetings. As for the left, they seem hindered by their own contradictions. From now on they champion the upper and middle classes but haven’t been known to listen to their traditional voters when grappling economic difficulties, and the tensions stirring up amongst communities in working class areas.

The epicentre of this ‘renewal of nationality’ is now central and eastern Europe. 'Ten years ago we were 'losers' to be nazis, now it’s ok to be a nazi. Who knows where we’ll be in ten years time?' concludes Peter, a campaigner for the national democratic party (NPD) in Bavaria, Germany.

Translated from L'extrême droite s'offre une seconde jeunesse sur le web