European social funds and the case of start-ups in France

Published on

Translation by:

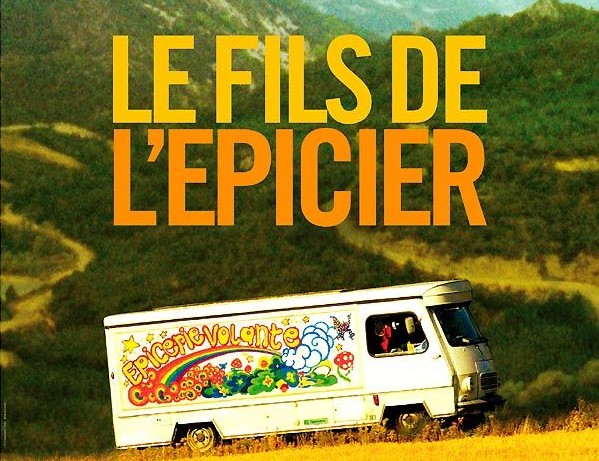

Sarah TruesdaleSetting up in business without any advice can be a little like doing sports without any training. There’s professional help available in the form of an entrepreneurial incubator; the ESF’s purpose is to finance these intermediary structures. In the 2007 French film ‘The Grocer’s Son’, a youth takes over his father’s rural travelling store - like Caroline

Caroline is in a hurry. Quickly, she smiles and after one last photo, she takes off: ‘I have another meeting at 8 o’clock,’ warns the CEO, who has been head of the ‘grocery girls’ since January 2009. At 43, with a short shock of blonde hair framing a mischievous face, the town councillor of Chissey les Mâcon (Saône-et-Loire) has ideas for sale. In April 2007, she quit her job as a French integration into employment counsellor (‘conseillère en insertion professionnelle’) to launch a career in the massage and aromatherapy industry. This was beneficial on two fronts. Firstly, the job centre steered her towards the ‘boutique de gestion’ ('management shop') in Saône-et-Loire in central France. This is a group which helps those who start up or take over businesses, and allowed her to learn the entrepreneurial industry ropes.

Caroline is in a hurry. Quickly, she smiles and after one last photo, she takes off: ‘I have another meeting at 8 o’clock,’ warns the CEO, who has been head of the ‘grocery girls’ since January 2009. At 43, with a short shock of blonde hair framing a mischievous face, the town councillor of Chissey les Mâcon (Saône-et-Loire) has ideas for sale. In April 2007, she quit her job as a French integration into employment counsellor (‘conseillère en insertion professionnelle’) to launch a career in the massage and aromatherapy industry. This was beneficial on two fronts. Firstly, the job centre steered her towards the ‘boutique de gestion’ ('management shop') in Saône-et-Loire in central France. This is a group which helps those who start up or take over businesses, and allowed her to learn the entrepreneurial industry ropes.

But more importantly, it was during her market research that she met Alain, a travelling grocer who was visiting several local villages in his J9 truck, which he had converted into a shop.‘I fell in love with the idea,’ she explains. Bingo! Back at the boutique de gestion, she was steered towards the enterprise incubator Potential 71 to help her with her new project. Alain was delighted to be able to go into retirement. ‘For a month, I followed him on his tours. We stopped in 17 little communes on the way and the older people were waiting for us each time. What impressed me most was the convenience, the solidarity and the true sense of service.’ Caroline took possession of the keys to the J9 in January 2009 and today, the grocery store has even launched a line of organic and local produce.

But more importantly, it was during her market research that she met Alain, a travelling grocer who was visiting several local villages in his J9 truck, which he had converted into a shop.‘I fell in love with the idea,’ she explains. Bingo! Back at the boutique de gestion, she was steered towards the enterprise incubator Potential 71 to help her with her new project. Alain was delighted to be able to go into retirement. ‘For a month, I followed him on his tours. We stopped in 17 little communes on the way and the older people were waiting for us each time. What impressed me most was the convenience, the solidarity and the true sense of service.’ Caroline took possession of the keys to the J9 in January 2009 and today, the grocery store has even launched a line of organic and local produce.

Twice the luck

Caroline smiles, then puts the microphone back at the front of the auditorium, sitting well behaved in the hall of the Palais de Congrès (convention centre) in Dijon, central-eastern France. She is used to telling her story, but the Job Creation Workshop organised as part of the ESF conference from 3 to 4 December 2009, brings a new dimension to the tale. Around a hundred job creation and restructuring professionals are listening to her with a critical but interested ear. ‘What’s the link between your activities and the ESF?’ asks one. ‘Boutique de Gestion and Potential 71 are financed by the ESF.’ In reality, the ESF doesn’t ‘finance’ projects, but will ‘co-finance’ up to 10% of the intermediaries of job creation: this is one way to not supplant organisms which already exist. The financial contribution is not that important, as one stakeholder says that that means sometimes waiting for 17 months to see the money.

So what is the purpose of the ESF? They help to place people back into the job market, provide continued training, fight against discrimination and encourage social cohesion: the ESF is an instrument of solidarity in the hands of the European states. To create work, in addition to financing organisms like France Active or the Boutique de Gestion, the ESF contributes to training support professionals, a fundamental mission according to the assessor of the operational programme of the ESF in France 2007 - 2013: ‘For those who work to create jobs, there is a doubled success rate for those who have help.’ Caroline agrees. ‘Without these bodies,’ she says, ‘it’s doubtful I could have met with success. They allowed me to be credible with bankers, to know how to put together a business plan and to feel supported.’

Crisis: a godsend

At a December conference on the role of the ESF during a time of financial crisis, where participants from 17 European countries shared their common experiences, the debates brought out a surprising admission: the crisis was an opportunity. In times of economic difficulty, salaried workers who lost their jobs tried their luck at creating their own businesses or at taking over their companies before they went into liquidation. The snag is that many unemployed youths launch themselves with no business sense, like athletes without training. ‘It’s the same everywhere in Europe,’ adds the head of the ESF in Flanders. ‘Young people are scared of unemployment, so they plunge themselves into running their own business, with no preparation. With no assistance, they will fail in less than two years.’ However, as Lenia Samuel, the head of social affairs and work for the European commission says: ‘Employment is the only way to escape the crisis.’ Yet another reason to support and better inform those who create and take over businesses, as only 20% of them will succeed in making their projects endure. You don’t need thousands to do this, says one friendly Belgian study: ‘You can start a business with 1500 euros.’

‘Scared of unemployment, young people plunge themselves into their own businesses with no preparation'

Caroline is the only woman amongst all the serious black suits. Before her speech, she confides that she will soon open a hostel where she will blend a relaxing space with the sale of organic products, an activity centre and a bistro. She is counting on the aid of the ESF and banks, but she didn’t expect to have the funds to launch herself into the business with three friends from the Vosges. ‘It was the letters of support that moved me. I’ll be able to permanently locate my business and make it profitable. Not only will it be profitable, but it will be humanised.’

Translated from Créer son entreprise: le coup de pouce de la crise économique