European Identity - What the hell does that mean?

Published on

Translation by:

Danny S.

Danny S.

"Europe lacks an identity." You can read that in any intellectual analysis. But our author hit the streets and the cafés of Strasbourg, philosophising with real people on the ground. But what the hell is European identity, in the minds of the people? In the end, we found a common denominator.

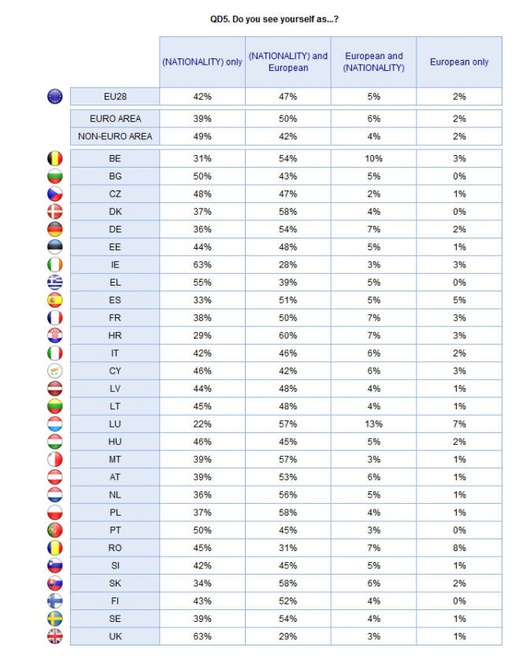

Once a year, the EU asks its citizens whether they identify themselves with their own nation or with Europe. It asks for the purpose of establishing a European identity. But what does European even mean? What is identity?

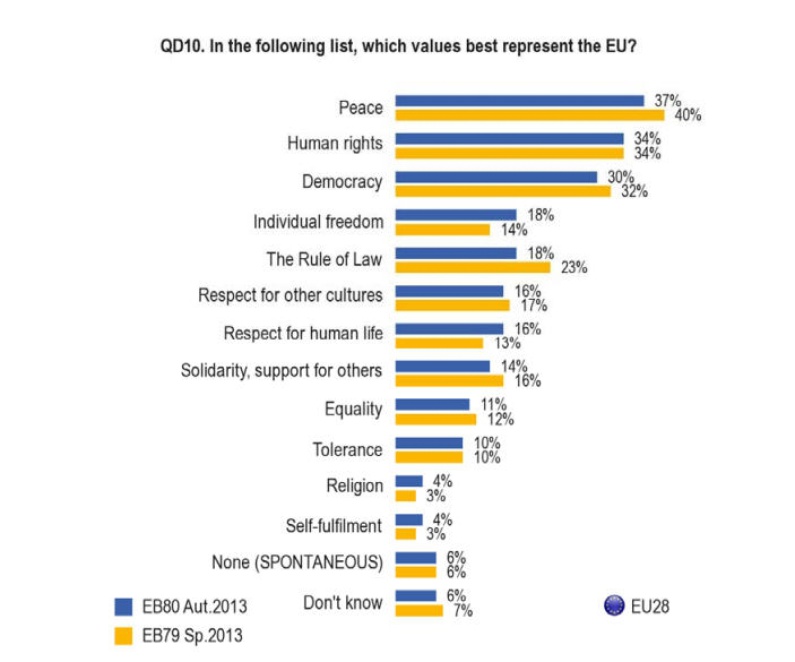

Diverse authors eagerly try to summarize these two words through lengthy essays, but wind up writing about democracy, about mutual values, about history and sometimes even about Christianity. But what do actual Europeans say when they're not presented with a multiple choice questionnaire from the statistical agency Eurostat? What do they say when asked why they feel, and in some cases don't feel, European? What better place to find out than in a city that claims to be a European city?

It's a sunny afternoon in Strasbourg, house boats are anchored along the Ill, bars and cafés line the river, people are sitting on lawn chairs and sofas, drinking, smoking, chatting. Next to me there's a black-haired, slightly plump middle-aged woman sitting across from her mother, who has somewhat haggard blond hair, she's slimmer and has a few wrinkles.

It's a sunny afternoon in Strasbourg, house boats are anchored along the Ill, bars and cafés line the river, people are sitting on lawn chairs and sofas, drinking, smoking, chatting. Next to me there's a black-haired, slightly plump middle-aged woman sitting across from her mother, who has somewhat haggard blond hair, she's slimmer and has a few wrinkles.

I carefully try to inch towards the simple question: "Is Strasbourg a European city?" "Yea," is her immediate response. Why? "Because so many tourists from different countries come here. There are foreigners everywhere," says the daughter. That's true, Strasbourg is a tourist hub. But if they're foreigners, then how can they be European?

"I know what you're getting at, but it's difficult to answer. Generally speaking, what does European even mean?" Yeah, exactly, what is it? Her mother chimes in and says it's the mutual customs that all Europeans share. And which ones would those be? "Good question." No response. Her daughter interjexts, "I lived a few years in Canada. I really felt like a European there. Everything there is somehow different. When I'm in Beligum, I'm a European. But when I'm in France, I'm French."

Other responses are similar. A Russian who moved to Strasbourg says she's seen as a European when she's back in her homeland, but in Strasbourg she's seen as a Russian. The definition of European seems to be unclear, an identification which they only seem to encounter when they leave their home and familiar culture. Clearly identity seems to be a form of demarcation. We and "the other."

Other responses are similar. A Russian who moved to Strasbourg says she's seen as a European when she's back in her homeland, but in Strasbourg she's seen as a Russian. The definition of European seems to be unclear, an identification which they only seem to encounter when they leave their home and familiar culture. Clearly identity seems to be a form of demarcation. We and "the other."

Do you primarily feel French and then European, or first European and then French? Both women respond, "French first." Does that mean that you care about the French first, before you care about other Europeans? Both reluctantly respond "yeah." But in some eastern member states people are dying of hunger and living in slums. Shouldn't they be given more immediate concern? "Yea, I know it's bad to think this way, but people are dying in France, too," says the daughter. Her mother continues, "of course we have to think globally, and when we do that, we have to make sure to take care of the weaker European countries. We have to stick together to survive in the faces of China and the USA."

She's not the only one who answers the question in this way.

First my livelihood, and then others'

An attractive French woman unlocking her bicycle signals that she's in a rush, but as I confront her with my questions she stands still and mulls it over. Even she says, "of course I'm firstly concerned about the French, but we have to show concern for the others, too." A group of youths, some of whom aren't even 18, lend an interested ear and try to give answers. In conclusion: "our parents taught us that we have to think of the other people in Europe, too."

In the end, everyone who was asked used the expression "we must." Not: "we should." Europe doesn't seem to be a matter of the heart, but rather a matter of the mind. Those who think of Europe are pragmatic, sober, rational and are conscious to see its economic benefits. Maybe the mutual virtues of the Enlightenment aren't so farfetched after all.

What better way to test this thesis than in a discussion about Europe. Twelve of my, for the most part young adult, friends accepted my Facebook invitation to discuss Europe in the student bar Le Chariot on a Friday around 8 o'clock. Some of them work for Cafébabel, others are either friends or acquaintances. Even here, with people who already deal with the topic, the message is similar; all but three people (myself included) identify themselves firstly with their own nation before identifying with Europe.

A thought: If one first identifies oneself with one's own nation, before identifying oneself with Europe, can that then be considered nationalism?

No one says a word.

I had posed the question just a couple of hours before as I spoke with people in the Palais d'Europe - the seat of the Council of Europe - all of whom looked like important people. Without hesitation, a delegate from the Kosovo parliament already had an answer ready. "It's not nationalistic; it's egotistical. But that's how everyone is. Everyone concentrates on themselves first before caring for others." In the bar Le Chariot, the first responses materialize. One of them says, "identity has nothing to do with nationalism. Just because one might view oneself as French, doesn't mean that person's a nationalist. It's only when one begins to marginalize other countries or see them as lesser that you can speak of nationalism." Nationalism is, in other words, something political, whereas identity is something cultural.

I had posed the question just a couple of hours before as I spoke with people in the Palais d'Europe - the seat of the Council of Europe - all of whom looked like important people. Without hesitation, a delegate from the Kosovo parliament already had an answer ready. "It's not nationalistic; it's egotistical. But that's how everyone is. Everyone concentrates on themselves first before caring for others." In the bar Le Chariot, the first responses materialize. One of them says, "identity has nothing to do with nationalism. Just because one might view oneself as French, doesn't mean that person's a nationalist. It's only when one begins to marginalize other countries or see them as lesser that you can speak of nationalism." Nationalism is, in other words, something political, whereas identity is something cultural.

And no one who attended wanted to replace this national, cultural identity with a European one. Ultimately, it's precisely cultural diversity that constitutes Europe. To think as a European apparently means to acknowledge the varied differences in Europe, and possibly even be proud of it. After all, the motto of the EU goes: "United in diversity."

However, in the conversations on the street, it became clear that many Europeans don't necessarily want solidarity, but rather that they need it. They maintain a rather pragmatic and rational relationship to the idea of "Europe." A relationship that's more of the mind than of the heart. They don't feel any pathos, don't have any patriotism, and don't have any love.

Ehrlicherweise müsste das Motto daher wohl lauten: trotz Vielfalt vereint.

In all honesty, the motto should rather go: despite divsersity, united.

his article is part of a special series devoted to Strasbourg. It's part of "EU-topia : Time To Vote", a project run by Cafébabel in partnership with the Hippocrène foundation, The European Commission, the Ministry of Foreign Affaires and the EVENS foundation. The whole series will soon be available on the homepage.

Translated from Europäische Identität - was zur Hölle ist das?