Europe at the Auction Block: Behind the TTIP Agreement

Published on

As all eyes remain fixed on the crisis in Ukraine, the European Union and the United States are in the process of negotiating the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), an agreement that could radically alter the trade relationship between the two blocs. President Obama, Europe is for sale!

This fall, it appears European institutions are smitten by trade agreements. On September 26th, the European Union (EU) and Canada concluded their negotiations for the EU-Canada Trade Agreement (CETA), which is now waiting to be ratified by European Member States and the Canadian provinces.

There is a second agreement in the works: the EU is in the midst of negotiations with the United States to develop the largest comprehensive free trade agreement in the world. Protests against the agreement sprung up in London, Berlin, France, Italy and Spain as citizens raised their concerns about the project.

For such a monumental occasion, the arbitration of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) has passed by largely behind closed doors on both sides of the Atlantic, out of the sight of citizens. However, there is reason to pay attention to the proceedings as the outcome promises to bring fundamental changes to the rules of global trade, particularly in the relationship between governments, corporations and citizens.

TTIP in a Nutshell

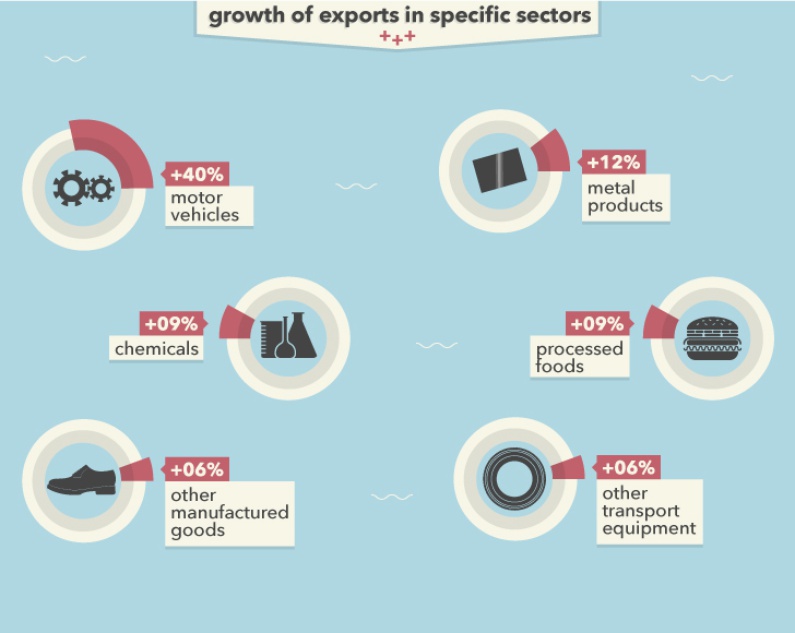

In a few words, the proposed agreement would mostly serve to restructure the existing trade relationship between the EU and the US, namely by cutting tariffs, removing trade barriers and harmonising industry standards and regulations that limit the exchange of goods and services to open market access. According to the website of the European Commission, the proposed treaty would save "unnecessary time and money for companies who want to sell their products on both markets." Large corporations would benefit greatest from this agreement, with specific sectors such as the motor vehicle industry and metal industry expected to increase exports upwards of 40% and higher revenue while cutting costs — some companies are expected to save up to 80%.

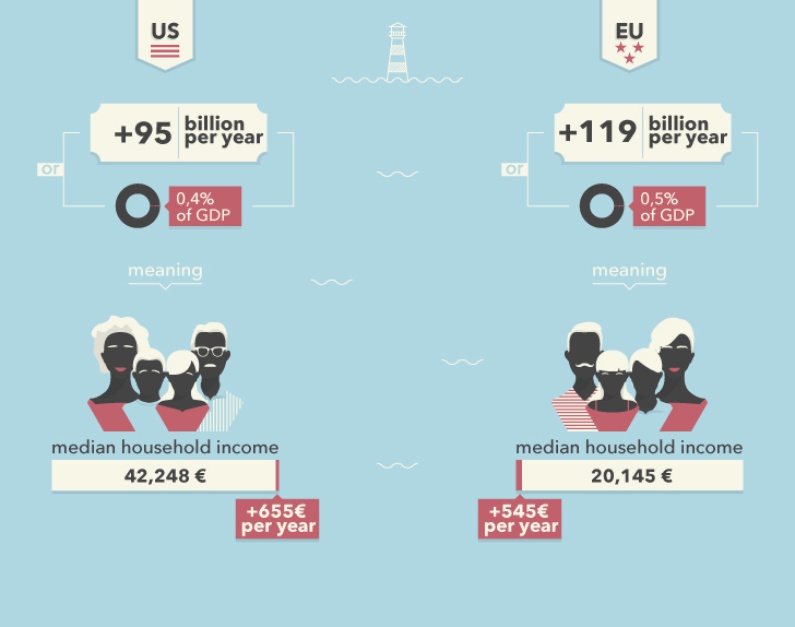

Another popular figure used to promote the treaty is the increase in gross domestic product (GDP) with the EU expected to enlarge the size of the economy per year by an extra 119 billion euros for the European economy and 95 billion euros to the American economy. However large these figures appear, they actually represent a paltry percentage of the total overall GDP for both, 0.5% and 0.4% respectively. This is particularly true when compared to the profits large corporations stand to gain if the treaty is ratified.

Another popular figure used to promote the treaty is the increase in gross domestic product (GDP) with the EU expected to enlarge the size of the economy per year by an extra 119 billion euros for the European economy and 95 billion euros to the American economy. However large these figures appear, they actually represent a paltry percentage of the total overall GDP for both, 0.5% and 0.4% respectively. This is particularly true when compared to the profits large corporations stand to gain if the treaty is ratified.

While touted as beneficial for the every European and American, citizens are expected to receive meagre returns from TTIP. The average European household of four would earn 545 euros more per year, a raise of roughly 2.7% in yearly income, based on data from Eurostat. In the United States, the average household would earn an extra 655 euros per year, an approximately 1.5% increase, from data compiled by the United States Census Bureau.

While touted as beneficial for the every European and American, citizens are expected to receive meagre returns from TTIP. The average European household of four would earn 545 euros more per year, a raise of roughly 2.7% in yearly income, based on data from Eurostat. In the United States, the average household would earn an extra 655 euros per year, an approximately 1.5% increase, from data compiled by the United States Census Bureau.

While the treaty would facilitate the free exchange for companies across borders, it makes no mention of increased mobility or freedom of movement for citizens, which could alleviate some of the high unemployment rate in the EU (11.5% as of August 2014), specifically among young people. It is also uncertain as to the exact amount of employment opportunities would arise from the agreement. According to the European Commission's Economic Analysis Explained, the number of jobs potentially created by the agreement cannot be "quantified", despite grandiose promises from European Commissioner for Trade, Karel De Gucht, that the treaty can create jobs.

Corporations vs. Governments: Who is the Real Winner?

The project would not only liberalise bilateral trade between the EU and the US, it also threatens to fundamentally alter the relationship between states and corporations, leaving governments vulnerable to legal action if their laws harm the profits of a corporation and their investors.

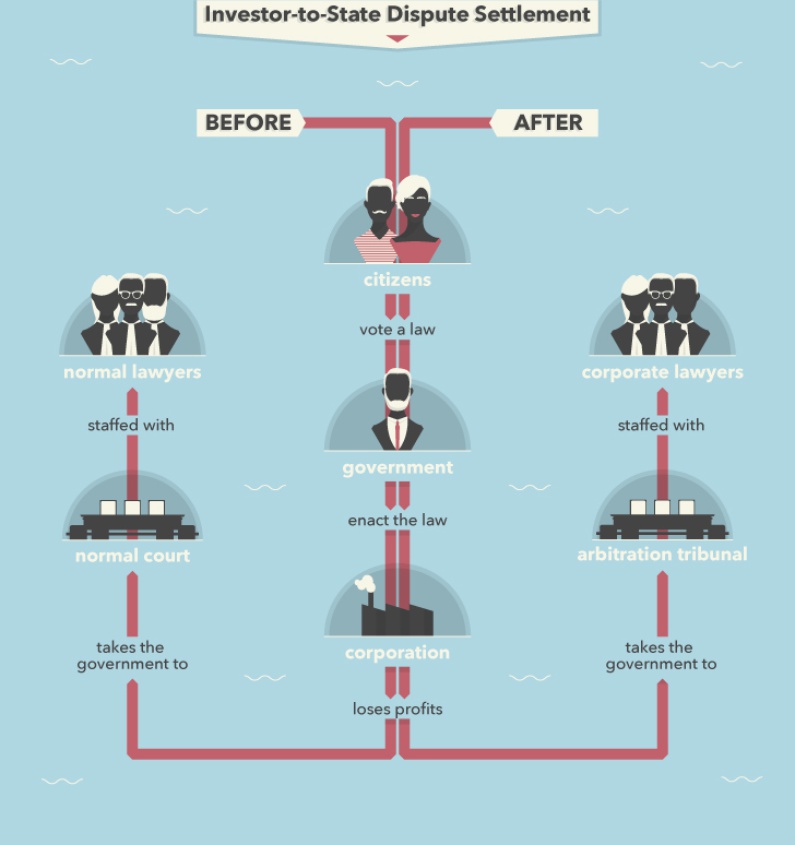

One of the most debated aspects of the TTIP is the channel through which such legal proceedings would be conducted. The Investor-to-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) allows a foreign investor to file lawsuits against a state if a change in government legislation or policy negatively affects their revenues. Although commonplace in free trade agreements, the clause is controversial; the European Commission received 150,000 registered concerns about the inclusion of the measure in TTIP via an Internet portal for citizens to give feedback about the negotiations, placing it among one of the biggest concerns for voters.

In the current model, corporations have the same access to legal recourse as any other entity or individual, placing them on equal footing with other members of society while simultaneously preserving the power of the state to enact laws that are demanded by the majority of voters. Meanwhile, the ISDS model separates the disputes of corporations into special arbitration tribunals, endowing companies with privileged and speedy access to judges, lawyers and the state. Thus, corporations are given priority to challenge government legislation which inconveniences their business practices, elevating them above citizens and governments in the process.

In the current model, corporations have the same access to legal recourse as any other entity or individual, placing them on equal footing with other members of society while simultaneously preserving the power of the state to enact laws that are demanded by the majority of voters. Meanwhile, the ISDS model separates the disputes of corporations into special arbitration tribunals, endowing companies with privileged and speedy access to judges, lawyers and the state. Thus, corporations are given priority to challenge government legislation which inconveniences their business practices, elevating them above citizens and governments in the process.

The Slippery Slope of Workers' Rights

Harmonisation does not necessarily translate into progress; often it corresponds to the lowest common denominator between two parties. As part of the push to harmonise labour standards across Europe and the US, concerns of the erosion of the rights of workers in the EU are warranted. The International Labour Organisation has established eight conventions to protect workers' rights. While EU Member States have ratified all eight, the US has only ratified two.

Another issue is the American penchant for disregarding the right to collective representation. In the context of TTIP, unions represent 'barriers' to international trade flows as do many of the entitlements European workers enjoy. As such, companies would be able to cherrypick where to base their operations by comparing the anticipated cost of labour — such as salaries, taxes, social contributions, holidays, benefits, and the strength of unions — and simply choose the cheapest and most 'hassle'-free country.

Another issue is the American penchant for disregarding the right to collective representation. In the context of TTIP, unions represent 'barriers' to international trade flows as do many of the entitlements European workers enjoy. As such, companies would be able to cherrypick where to base their operations by comparing the anticipated cost of labour — such as salaries, taxes, social contributions, holidays, benefits, and the strength of unions — and simply choose the cheapest and most 'hassle'-free country.

Smoke and mirrors

Despite all the controversy, the most troubling aspect of the TTIP is the lack of public involvement in the negotiations. The process has transformed into a back door deal between detached bureaucrats and the business people with vested interest in the ratification of the agreement instead of an active consultation process that adequately includes citizens in the proceedings. As the rhetoric surrounding the TTIP focuses on investors, states should consider their citizens as their investors, each given one share in the form of a vote, and thus, have the right to be involved in the decision-making process.