Europe and the Syrian civil war: Greater crises await

Published on

European countries have recently committed themselves further into the Syrian civil war. What exactly have they got themselves into, and where will this ultimately take Europe?

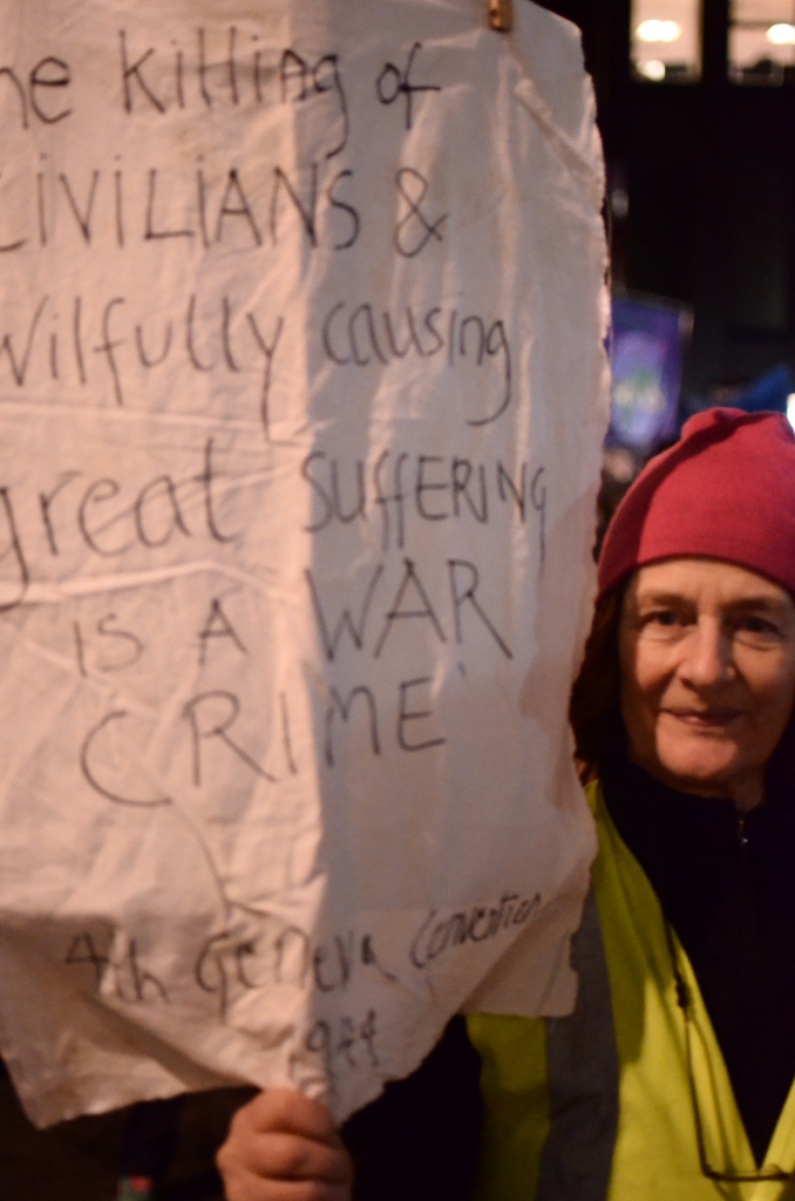

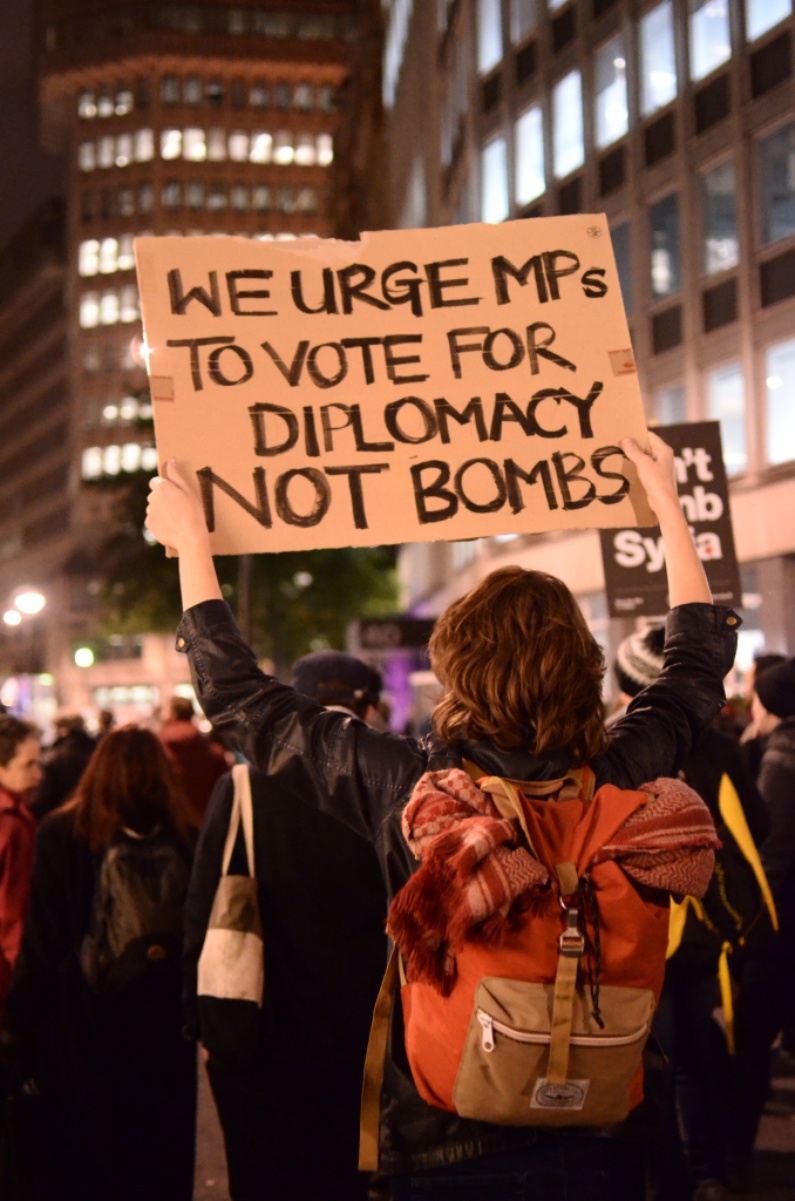

Last week I was outside the Houses of Parliament the night before the Commons debated the UK Government’s motion to intervene in Syria, of which the key and controversial component was the extension of airstrikes from Iraq to Syria.

Stop the War Coalition campaigners were out en masse to protest against the prospect of Britain bombing Syria. In part the Government was responding to French allies’ calls –after the tragic attacks of November 13th in Paris – to join them in their effort to strike down the group called ISIS, Daesh, or even the "so-called Islamic State" as is the BBC's preferred term.

In the end, after a long debate and sensational ending speech by Shadow Foreign Secretary Hilary Benn, MPs voted for the motion and Britain answered France’s call committing 16 more jets to those already bombing Daech in Iraq.

On Friday 4th December, the German parliament also voted to assign military personnel to the region, showing it is serious about it's display of solidarity with France.*

Belgium and Denmark are already involved in the coalition’s efforts. The conflict that Europe is now effectively engaged in in the Middle East has many implications; and the devil is in the many implied details, details that ultimately matter to Europe.

One of the problems the war is increasingly presenting for Europe is the amount of displaced people it is generating, many of whom seek refugee status. Germany has so far born the brunt of Europe’s responsibility towards refugees – which hasn’t helped Merkel at home – where Eurosceptic parties like Alternative for Germany have been growing in influence.

One of the problems the war is increasingly presenting for Europe is the amount of displaced people it is generating, many of whom seek refugee status. Germany has so far born the brunt of Europe’s responsibility towards refugees – which hasn’t helped Merkel at home – where Eurosceptic parties like Alternative for Germany have been growing in influence.

The other problem is the threat of terrorism from Daesh, which has declared war on all who don’t agree with its absolute worldview. Funded by Saudi Arabia and Qatar (who are supposed to be Western allies), they are well organised and currently hold territory in Syria and Iraq including the cities of Raqqa and Mosul, a city of 1.5 million people.

The decision to extend bombing must be understood in a post-November 13th context. In military terms it doesn’t make much sense when there aren’t enough co-ordinated ground forces to take the fight to Daesh. The coalition won’t be putting any boots on the ground, only bombing from the air.

The decision to extend bombing must be understood in a post-November 13th context. In military terms it doesn’t make much sense when there aren’t enough co-ordinated ground forces to take the fight to Daesh. The coalition won’t be putting any boots on the ground, only bombing from the air.

This means progress to eliminate Daesh from its strongholds will be slow, because – as Barry Gardner MP explained in the Commons debate – airstrikes are designed to create a moment of opportunity for ground forces to move in. If ground forces aren’t there in practice, that opportunity is lost.

The coalition may claim to have incapacitated or eliminated many of Daesh's leaders and fighters, but as American intelligence officials have said, the group is difficult to destabalise thanks to its decentralised organisational structure.

Therefore until ground forces get organised, airstrikes will remain largely ineffectual. What's more is that this may just create more refugees, which will compound Europe’s problems further. Awfully, more innocent civilian lives may also be lost as a result.

The UK may ostensibly be aiming to limit civilian casualties, but given that these civilians will be Sunnis – who, as pointed out by Sir Edward Leigh MP during the Commons debate, may well prefer Daesh to the ruling Shia militias, even though they do not share Daesh’s extremist views – they may be driven to join Daesh’s ranks if they see the West bombing them.

The UK may ostensibly be aiming to limit civilian casualties, but given that these civilians will be Sunnis – who, as pointed out by Sir Edward Leigh MP during the Commons debate, may well prefer Daesh to the ruling Shia militias, even though they do not share Daesh’s extremist views – they may be driven to join Daesh’s ranks if they see the West bombing them.

Regardless, Daesh can be counted on to use these strikes to fuel their propaganda campaigning, encouraging as many people as possible to join their jihadi war. Since Daesh control a region with a population of around 6 million, the military consequences for both Europe, as well as the region itself, are unknown and far-reaching.

Around 9 million Syrians have fled the country so far, with 1.6 million currently in Turkey. They could well decide to make Europe their home if they can’t see the civil war ending soon. The possibility of yet more refugees arriving in the EU also puts the Schengen agreement under increasing strain.

In order to deal with this crisis, the EU is giving Turkey 3 billion euros to help stem the flow of refugees across its border. Turkey has come under scrutiny by Nato allies for its border management as it effectively allows Daesh to use it to sell oil. A complicated relationship with Kurdish forces also fighting in the region makes it harder for Turkey to decisively support either side.

In order to deal with this crisis, the EU is giving Turkey 3 billion euros to help stem the flow of refugees across its border. Turkey has come under scrutiny by Nato allies for its border management as it effectively allows Daesh to use it to sell oil. A complicated relationship with Kurdish forces also fighting in the region makes it harder for Turkey to decisively support either side.

These points of concern were both raised in the Commons, by speakers as wide ranging as rebel conservative David Davis and former SNP leader Alex Salmond. If Turkey continues this strategy, and depending on which way the war goes, Europe may have no choice but to take firm diplomatic action, perhaps withdrawing the pledged funds. The longer it takes for Daesh to be destroyed, the more refugees will likely come to Europe, and the longer the terrorist threat will remain.

*This article was amended on 17th of December. The original stated that Germany had committed ground troops in Syria. In fact they have committed 1200 'military personnel' but will not join air strikes.

*This article was amended on 17th of December. The original stated that Germany had committed ground troops in Syria. In fact they have committed 1200 'military personnel' but will not join air strikes.

---