Europe and exclusion

Published on

Translation by:

fiona wollensack

fiona wollensack

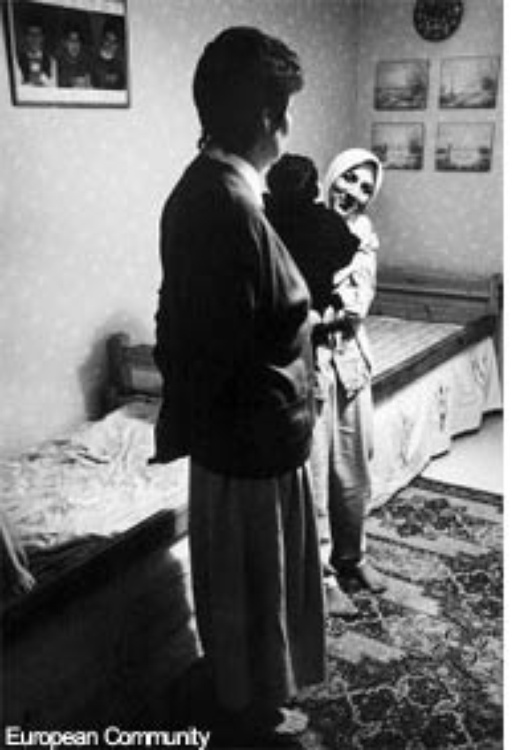

Through the debate on identity and the questions of expansion and immigration, Europe is trying to establish its boundaries. Borders give a sense of safety and security, but can also be a source of repression for those on either side of them

Today’s Europe has come to be a collective system of states dissected by borders. The European invention of territorial states with defined borders has, along with capitalism, come to represent the standard model of political organisation. To define political identity as belonging to a particular people or a nation state has become such an accepted norm to us that the existence of geo-political borders and identity derived from national citizenship seem perfectly natural.

Today’s Europe has come to be a collective system of states dissected by borders. The European invention of territorial states with defined borders has, along with capitalism, come to represent the standard model of political organisation. To define political identity as belonging to a particular people or a nation state has become such an accepted norm to us that the existence of geo-political borders and identity derived from national citizenship seem perfectly natural.

The rigidity of borders surrounding nation states has been notably decreased through the transnational flow of people, information, goods and capital. But running counter to this trend has been Europe’s creating and strengthening of borders. Thus, whilst the internal borders of the EU have decreased in importance, its external borders are being consolidated, step by step.

An integral part of this process is the debate being held by the ruling elite about European identity. The construct of identity goes hand in hand with the construct which arises from the debate on identity, the construct of “other”. In other words, of a non-European identity. This is not only the antithesis of the European identity but also that which European identity must protect itself from. “Other” can be defined as a variety of things: the threatening Muslim identity (Turkey, terrorists); the threateningly chaotic (the Balkans, Russia); the threateningly unilateral (the USA or President George Bush); the threateningly foreign and unfamiliar (alternative ways of life penetrating to the core of Europe’s). Each of these different identities must either be assimilated and integrated, or kept out altogether. The borders of Europe which have arisen from the debate are the justification for the very real creation of a “Fortress Europe” which will ensure that through its external borders, Europe and its fragile identity can be protected

Exclusion and adjustment

Borders serve the purpose of protecting what lies inside. They are, however, predominantly repressive. Borders serve to legitimate and secure privileges: in their apparently self-understood nature, borders persuade citizens of the Union that they have a legitimate right to the Union’s territory and the values it holds. That “others” should have the same right as “we Europeans” to move freely on European territory or settle there, that “others” should be granted the same democratic rights of co-decision as “we Europeans” are considerations which get lost in a reality in which borders are considered quasi-natural norms.

So that the homogenous identity which has been constructed for those within the borders can be kept “pure”, differences must be negated. The non-European within Europe must be assimilated, Europeanised and normalised. The only acceptable “strangers” amongst us are those that fit into the dominant European culture. Borders can only maintain their function if the fiction that they cleanly separate the homogenous internal identity from the “other” external identity is maintained.

Post-modern Europe

European integration offers the perfect opportunity to overcome the modernistic, territorial-focused perception which now dominates and is strongly characterised by its blinkered thinking. European politics is a heady mixture of differing and overlapping loyalties, all at different levels. Europe’s borders remain preliminary, movable markings, especially with the continued existence of the movement advocating further enlargement of the EU. And European identity finds itself in a similar state of flux as its borders. Modernistic thinking is pushing for a decision on the matter: “Where are Europe’s borders? What constitutes the European identity? Who is a part of it and who is not?” The temptation to answer these questions once and for all, so as to finally provide clarity and order, must be resisted. It is the openness, the indecision and changeability, the overlapping, the multiple, the nebulous, the fluid, which make Europe an exciting post-modern project. There is significant potential in a post-modern Europe to grasp new ways of thinking and living and to develop democratic forms which could help avoid the totalitarian and repressive aspects prevalent in the modern system of the nation state.

Translated from Europa und die Aus-Grenzung des Anderen