Enki Bilal: 'My cartoons evoke a past out of step with reality'

Published on

Translation by:

claire hooper

claire hooper

The Czech-Bosnian cartoonist, 55, weaves between cartoons, cinema and geopolitics, taking his readers on a trip into a futuristic universe where political commitment is key

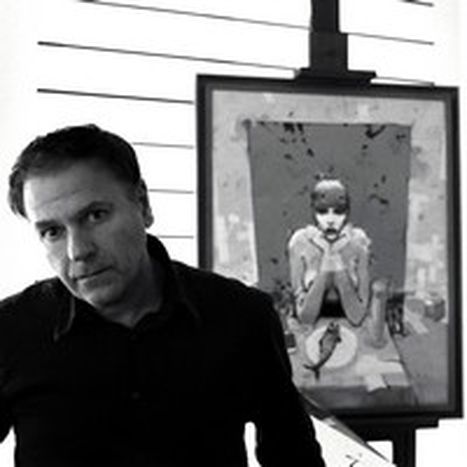

‘There's a little of me in all my characters,’ says cartoonist Enki Bilal. A little of him in Jill Bioskop, his blue-haired comic heroine-cum-journalist of Femme Piege (‘Woman Trap’, 1986). A little of him in Alcide Nikopol, the rebellious astronaut with a sad gaze. From anagram to pictogram, his beautiful yet desperate heroes roam tirelessly in murky, poetic universes which have earned their author critical recognition and public fascination. In his Parisian workshop, watched over by the Saint-Eustace church, the long drawing-tables cluttered with sketches are flooded with light, while a luxurious Mac chats to a stuffed zebra’s head.

A flowing, dark figure, with fine features and soft pupils, Bilal rests but doesn’t stay seated. He has just finished the last volume of his tetrolagyLe Sommeil du Monstre (‘The Dormant Monster’, 1998), three books which are similar to a ‘graphic novel’ completed over twelve years. ‘This series may demand more effort from the reader to understand. But my commitment was more personal,’ Bilal admits. ‘I don’t like making concessions. I reject the tyranny of simplicity, the pre-chewed, the pre-fabricated.’

A flowing, dark figure, with fine features and soft pupils, Bilal rests but doesn’t stay seated. He has just finished the last volume of his tetrolagyLe Sommeil du Monstre (‘The Dormant Monster’, 1998), three books which are similar to a ‘graphic novel’ completed over twelve years. ‘This series may demand more effort from the reader to understand. But my commitment was more personal,’ Bilal admits. ‘I don’t like making concessions. I reject the tyranny of simplicity, the pre-chewed, the pre-fabricated.’

Rootless

This rejection of compromise and an acute sense of commitment have so far suited the former Belgrade resident down to the ground. In 20 years, Bilal has become a legend of what is dubbed the 'ninth art' in France. He is also known in countries as far as Japan, albeit in the realm of manga. His drawings, suffused with a futuristic urban atmosphere, are systematically entangled with political reflections and firmly fixed in the world of today.

At the top of his list of concerns is the clash of civilisations or ecology. ‘The imaginary should serve the fund,’ affirms Bilal. Even if the 'past doesn’t interest me as such, it’s how out of step with reality it is that leads me to evoke it,’ he justifies. ‘I am part of this world. Not talking about it seems wrong to me.’

Born in Belgrade to a Czech mother and Bosnian father, the man left Marshal Tito’s Yugoslavia for France in the seventies. ‘I was 10. Leaving was brutal. A real wrench,’ he remembers with a dark, vague gaze. ‘At the same time, it was predictable. My father, Tito’s former official tailor, had been on a ‘business trip’ for too long.’ The arrival of the little Yugoslavian in Paris was a ‘disappointment’, especially where living conditions were concerned. He integrated ‘relatively well’ and Bilal has retained the love of the French language and his taste for the mot juste of this ‘nebulous period’.

Passionate about art and cinema, Bilal discovered a 'wonderful means of adult expression’ in comics, in the midst of their heyday in that period. Rapidly published in what is known as the then-best comic serial magazine in France, Pilote, he drew his first drawing boards for Echos des Savanes or Métal Hurlant. His hugely successful first trilogy Nikopol was completed thirteen years after he first began work on it in 1980.

Passionate about art and cinema, Bilal discovered a 'wonderful means of adult expression’ in comics, in the midst of their heyday in that period. Rapidly published in what is known as the then-best comic serial magazine in France, Pilote, he drew his first drawing boards for Echos des Savanes or Métal Hurlant. His hugely successful first trilogy Nikopol was completed thirteen years after he first began work on it in 1980.

Bilal's peers have already accepted his talent by awarding him first prize at the Angoulême International Comics Festival in 1987. ‘Cartoonists are real authors. The comic is a literary genre of its own,’ insists the prizewinner. For all that, it’s not a matter of confining it to science fiction – ‘fifteen years ago, events like September 11 or the concept of a face transplant were unimaginable.’ If the world is ‘speeding up’, the bubble's ‘environment’ seems to have become more ‘conservative’.

Bilal's peers have already accepted his talent by awarding him first prize at the Angoulême International Comics Festival in 1987. ‘Cartoonists are real authors. The comic is a literary genre of its own,’ insists the prizewinner. For all that, it’s not a matter of confining it to science fiction – ‘fifteen years ago, events like September 11 or the concept of a face transplant were unimaginable.’ If the world is ‘speeding up’, the bubble's ‘environment’ seems to have become more ‘conservative’.

Stage world

A nomadic artist, fleeing ready-made labels - ‘such a typically French habit’ - Bilal first embarked on film set construction before moving on to specialise in stage design. A ‘pleasant encounter’ at the beginning of the nineties with compatriot Angelin Preljocaj, a choreographer of Albanian origin, led him to stage design for dance. With Russian Sergei Prokofiev's ballet version of Romeo and Juliet the two artists successfully blended ‘two artistic universes linked by a Balkan eye.’

Bilal chops and changes. This eclecticism, far from expressing ‘frustration’ with regard to comics, demonstrates a constant discipline and curiosity. ‘I have never had a career plan – everything depends on people and on luck.’ Another passion he has is the cinema, which leaves him with an ‘unpleasant’ taste in his mouth. The cartoonist brought several of his albums to the big screen: Bunker Palace Hotel (1989), Tykho Moon (1996) and Immortel (2004) were relative commercial failures. ‘I don’t do conventional things,’ he retorts. ‘It’s difficult to admit artistic duplicity. A cartoonist who does cinema just doesn’t fit into any of the boxes.’ Silence.

The conflict in the former Yugoslavia has not ceased to ‘feed’ his work, and justifies his geopolitical commitments. ‘I was sickened by the attitude of Europeans, particularly Germany’s rush to recognise Croatia, which sped on Yugoslavia’s collapse,’ he levels. Just as much as by the ‘taking of radical positions by ‘certain’ French intellectuals. ‘There are no sides to take in this,’ he says, sounding rebellious, someone who proclaims his attachment to ‘victims’.

Europe is another topic dear to his heart. By virtue of his roots, Bilal naturally remains attached to the eastern countries which ‘hurried towards the Western dream.’ The expansion took place too quickly, too ‘eagerly’, giving way to disappointment and frustration. ‘What is to become of the planet is a subject that calls out to me, knowing how we are to survive and adapt.’

All photos: Jef Bonifacino

Translated from Enki Bilal : « Ne pas parler de ce monde me semble indécent »