England as an object of pilgrimage

Published on

Can nationalism fit into a religious costume? Is it possible that a place of pilgrimage can be modeled in such a way so that the worshipers honor something more than the deity? When I was given the task to map the inside of the Walsingham temple through an LSE project, I didn’t expect that the building would reveal itself in such a way that the above questions would become central to my analysis.

Therefore, it seems that the Walsignham temple is something more than just a place of worship, where the faithful English honor not only the Nativity and the Holy Passion but they pay their respects to the Nation. Along with the Virgin and the Child, it is England itself, which is the object of pilgrimage.

The Anglican Temple of Walsingham follows as a building, a very old Christian tradition according to which the church has to be modeled in the sign of the Cross. At the center of this cross, the house of the Nativity is to be found, surrounded by small chapels. The first chapel that is to be seen when the visitor enters is that of the Annunciation. This is the first episode of the narration about the birth of Jesus, when the Archangel Gabriel salutes Virgin Mary in order to inform her that she is going to give birth to the Son of God. In that way the narration of the Gospels gets vivid in front of the visitor.

Behind the small chapel is the replica of the House of the Nativity. The inside of the house, which according to the tradition was made under the guidance of the Virgin, is marked by a huge altar which is dedicated to the Nativity and it is the main side of pilgrimage. Three pictures from the life of the Virgin have been depicted, all in Renaissance style. The first one on the left is once again the Annunciation and the third one is the meeting of the Virgin and Elizabeth. The central image, which is the most dominant of the three, is the Pilgrimage of the Kings. There are many reasons that make this image quite interesting. Firstly, this theme was a very popular one during the Renaissance. It is quite impressive the Anglicans not only reproduce this theme but they also follow the Renaissance style in terms of iconography. The picture follows the historical anachronism that was typical in 15th century Italy, in terms of the costumes of the biblical figures. A possible explanation for this choice could be a restoration of the ‘continuity’ of the holy site, since it was originally a Roman Catholic Church until the Reformation. However, this image holds another symbolism which is pretty much apparent; as the three Kings came all the road to Bethlehem in order to pilgrimage the Lord, the same pattern has to be followed from the faithful Christians in Walsingham, ‘England’s Nazareth’.

The house is a reconstruction of the replica of the home

where Jesus was brought up in Nazareth. Impressively, the house has no other

windows but one, which faces the main altar of the church, which holds the same

picture of the ‘‘Pilgrimage of the Kings ’’. At the outside of the building,

the visitor can notice a number of old stones. As the parish priest informed

me, these stones come from various ruined monasteries and churches throughout

the country. They have been sent when the shrine was rebuilt at the beginning

of the 20th century.

The house is a reconstruction of the replica of the home

where Jesus was brought up in Nazareth. Impressively, the house has no other

windows but one, which faces the main altar of the church, which holds the same

picture of the ‘‘Pilgrimage of the Kings ’’. At the outside of the building,

the visitor can notice a number of old stones. As the parish priest informed

me, these stones come from various ruined monasteries and churches throughout

the country. They have been sent when the shrine was rebuilt at the beginning

of the 20th century.

Small chapels, three on the east side and five on the west side surround the house.

On the east side, the first chapel is dedicated to St.

Augustine of Hippo. As this saint is regarded as the father of Western

Christianity and theology, his presence at Walsingham is quite

understandable. Above that, the

chapel of St. Anne is to be found. Even thought the chapel is dedicated to the

mother of Virgin Mary, here the main theme is the presentation of Jesus at the

Temple. Here as well the painting follows the style of Renaissance Italy and

the figures are made on Medici style. The third chapel eastwards of the house,

is dedicated to young people. This signifies an effort made by the Church in

order to bring closer the youth. According to the parish priest, this helps

young people to believe that they have their own ‘place’ within the shrine.

Here, the fresco is presenting the famous episode from Luke’s gospel, where St.

Joseph and Mary find young Jesus teaching at the Temple of Solomon.

On the east side, the first chapel is dedicated to St.

Augustine of Hippo. As this saint is regarded as the father of Western

Christianity and theology, his presence at Walsingham is quite

understandable. Above that, the

chapel of St. Anne is to be found. Even thought the chapel is dedicated to the

mother of Virgin Mary, here the main theme is the presentation of Jesus at the

Temple. Here as well the painting follows the style of Renaissance Italy and

the figures are made on Medici style. The third chapel eastwards of the house,

is dedicated to young people. This signifies an effort made by the Church in

order to bring closer the youth. According to the parish priest, this helps

young people to believe that they have their own ‘place’ within the shrine.

Here, the fresco is presenting the famous episode from Luke’s gospel, where St.

Joseph and Mary find young Jesus teaching at the Temple of Solomon.

As we walk westwards of the house there are to be found five chapels, the symbolism of which strengths my argument, that indeed the shrine in Walsingham does not represent a ‘national pilgrimage’ but a ‘pilgrimage of the Nation’. The first one is dedicated to St. George, patron saint of England. The main picture presents the Agony of Jesus in the Garden before his arrest.

Westwards from St. George’s chapel, there is a chapel dedicated to two Celtic saints, St. Wilfred and St. Cuthbert. Next to this chapel there is the chapel of St. Hugh and St. Patrick.

All these saints are somehow connected to Britain’s history. The most famous, St. George and St. Patrick are patron saints of England and Ireland respectively, and their place in a place of national pilgrimage can be easily understood. However, it is interesting that all the saints in these chapels are connected to the ‘national narrative’ of British history. St. Hugh, St. Wilfred, and St. Cuthbert have their own story to tell which is connected to famous events of the British history. Therefore, their stories justify their presence in the shrine. St. Hugh, was bishop of Lincoln and his story is connected to the arrival of the Normans, while St. Cuthbert is connected to the Celtic Church (Wales, Scotland). Last but not least, St. Wilfred has a story with significant importance in the life of the Church of England. During his days, the English Church was in a debate on which church should it follow (the Celtic or the Roman). Even though those bishops who were in favor of the Roman Church finally prevailed, St. Wilfred was one of the most famous supporters of the Celtic tradition. Therefore, we can notice that his presence in the shrine symbolizes the strong anti-papal sentiments of the British, upon which their religious (and progressively their national) identity was built.

All these three chapels have been decorated by a female artist who lived in Little Walsingham, and who managed to paint them in three different artistic styles.

As we move with direction to the main part of the shrine, we find St. John Viamey’s chapel. This is dedicated to the parish priests who they regard St. John Viamey who was ‘‘cure d’ Ars’’ as their patron saint. The last chapel honors Virgin Mary and St. John, the disciple of Jesus. Various statues are decorating the chapel, with most predominant the ‘’Death on the Cross’’. This moment of the Holy Passion imply to us the meeting of St. John with the Virgin, where Jesus from the Cross made them ‘mother and son’.

The main hall of the Shrine is divided in three parts with

seven arches in each side. Above of the arches there can be found three heads

in each side, which depict people who somehow were involved to the revival of

the shrine. Next to the altar in

each side, one can notice a series of chairs, which remind a Synod. All these

seats bear the name of western saints who are connected to the Diocese of

England, St. Augustine, the Virgin Mary and one seat dedicated to all the

saints. In each seat, despite the

name of the holy people, there are inscribed the name of the priests who

currently seat or had seat in the past in order to ‘represent’ a saint

according to the ‘Apostolic sequence’. In any case it is important to stress

that all these seats (which are appointed by local bishops to priests)

symbolize a synod of the British people.

The main hall of the Shrine is divided in three parts with

seven arches in each side. Above of the arches there can be found three heads

in each side, which depict people who somehow were involved to the revival of

the shrine. Next to the altar in

each side, one can notice a series of chairs, which remind a Synod. All these

seats bear the name of western saints who are connected to the Diocese of

England, St. Augustine, the Virgin Mary and one seat dedicated to all the

saints. In each seat, despite the

name of the holy people, there are inscribed the name of the priests who

currently seat or had seat in the past in order to ‘represent’ a saint

according to the ‘Apostolic sequence’. In any case it is important to stress

that all these seats (which are appointed by local bishops to priests)

symbolize a synod of the British people.

In the southwest of the House of Nativity, the holy well is situated. This was the second well to be found in the area during the revival of the shrine and the locals regarded it as the proof that indeed divine power eulogizes the shrine.

On the upper floor a small Orthodox chapel has been established, since the revival of the shrine. The Orthodox priest informed us that this small chapel is one of the most old pan-Orthodox shrine to be found in East Anglia.

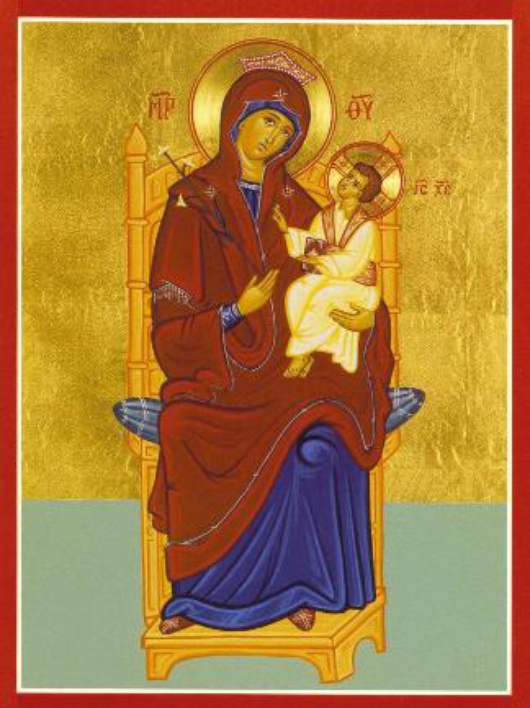

Lady of Walsingham in both Anglican and Byzantine styles!

The chapel is dedicated to Virgin Mary, however it follows the eastern Orthodox pattern not only in terms of art (the icon of Virgin Mary of Walsignham is the same as the Anglican statue but the Virgin is been depicted in the icon according to the Byzantine prototypes) but also in terms of worship. The small chapel reminds a miniature of a Russian Orthodox Church with the famous onion-like domes.

Next to the Orthodox chapel, in the middle of the floor, there is another holy altar of the shrine. Inside, a big picture of Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ dominates the space while in the iron gates of the altar two symbols of Jesus can be traced: the holy heart bearing the crown of thorns and a stork feeding his children by self-damaging. The holy heart symbolizes the Holy Passion while the stork is famous in Christian tradition as a bearer of spring, which symbolizes the Annunciation and Mary’s qualities of piety and chastity[1] .

In conclusion, the mapping of the shrine indicates that indeed this place was rebuilt under the mindset of building a ‘national shrine’. Despite the fact that long before the shrine was Roman Catholic, the new shrine was decorated and rebuilt with a strong sense of national identity. Around the House of the Nativity, the Anglicans try to ‘protect’ the English identity of the place. The saints of the British isles, the Celtic tradition (which arose significantly during the early 20th century) and the stones carried from every ruined church of Britain, they all create a symbol of national unity, a place of national pilgrimage where the faithful are called- implicitly- to give their respects not to the Lord or the Church but to the Nation itself.

[1] Bailey, Colin J. The Art Quiz Book: 2000+ Questions on Painters and Paintings. Station Press: Scotland, 1995.

© Cafebabel Greece