![Image for [eng] Migrants and Modernity between Europe and the Mediterranean](https://media.cafebabel.com/resized-images/7d/d5/770cab55c34233e14aa235694108dc4cd9bf.png)

[eng] Migrants and Modernity between Europe and the Mediterranean

Published on

Translation by:

Diane KimOn October 3rd, off the shores of Lampedusa, over 300 asylum seekers were pronounced dead after the vessel carrying them caught fire and capsized, marking yet another tragedy tied to irregular immigration and rekindling the neverending debate on the topic in Italy.

On the morning of October 3rd, off the coast of Lampedusa, a ship carrying around 500 migrants capsized and was caught in flames before it was able to reach shore. More than half of the migrants on board perished or are still considered missing, and following the incident, Giusi Nicolini, mayor of the island, requested logistical help in managing the emergency.

What had essentially occured was an unprecedented disaster that succeeded in breaching the persisting apathy over the plight of migrants landing in Lampedusa and rousing public opinion to the point where the State decided to dedicate a national day of mourning to the tragic event.

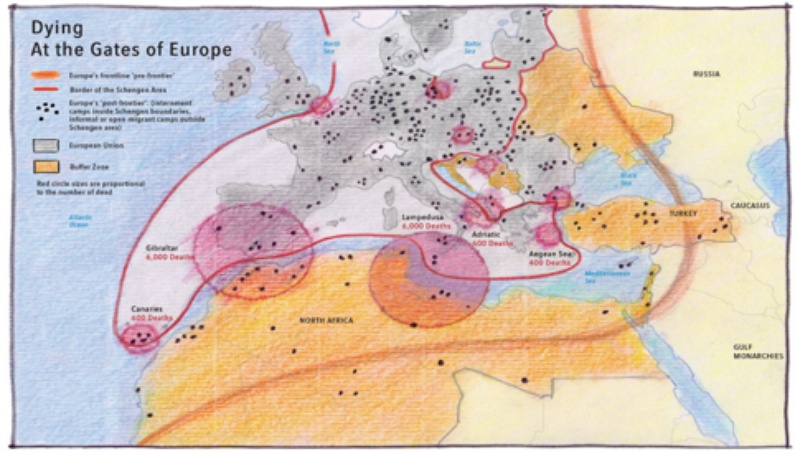

Those interested in the topic know, however, that this is hardly the umpteenth ordeal tied to illegal immgiration recorded solely in our country: it was followed, sure enough, by a similar episode along the Maltese coasts, and just one week before the incident in Lampedusa, another group of thirteen immigrants were forced to throw themselves into the open sea off the coast of Ragusa (the Republic of Dubrovnik). It is calculated that in the past twenty years, around 6,000 people have died seeking to cross the Mediterranean.

A more in-depth analysis reveals that the tragedy isn’t just the tip of the iceberg of years of contradictions of migratory policies in our country. The constitutionality and coherence with international law of policies in large part already launched in the 90s and then readdressed by the well-known Bossi-Fini laws have always been doubted, in addition to European Union directives recognized by Italy in a distorted manner.

The mayor of Lampedusa recounted that three fishing boats were present on the spot at the moment the boat capsized, but did not intervene for fear of being accused of assisting in illegal immigration, an issue anticipated and addressed by the Bossi-Fini laws. Perhaps the captains remembered the events of August 8, 2007: two Tunisian fishing vessels saved 44 migrants from drowning, but because the vessels had transported the migrants to Lampedusa without entry visas, the boats’ captains were subjected to a judicial process that lasted four years and their fishing vessels remain confiscated to this day.

Beyond the spectrum of possible ethical debates, this accusation also conflicts with Article 98 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, according to which the master of a ship is required to render assistance to any person found at sea in danger of being lost, and to intervene with all possible speed to the rescue of persons in distressed if informed of their need of assistance, in so far as such action may be reasonably expected. Both the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue and the International Convention for Safety of Life at Sea, which obligate at all times maritime rescue and deliverance of refugees to a place of safety “regardless of the nationality or status of such a person or the circumstances in which that person is found.”

The surviving migrants are now also accused of violating immigration laws. This accusation was condemned by the European Commission on Human Rights on the grounds that it was in contradiction with the concept of fundamental human rights, with European legislation (Directive 115 of 2008) and with international treaties ratified by Italy, such as the Geneva Convention.

The accusation of illegal immigration is furthermore unconstitutional seeing that it punishes the individuals in question not for their actions but for their status, for the simple fact of finding themselves under a personal condition over which they had no control. Such an accusation contrasts with the principle of equality before the law and with the constitutional guarantee on criminal cases, on the strength of which one can be punished only for concrete violations.

Even those who have the right to international protection but arrive without sanction (it is virtually impossible to obtain international protection while remaining in ones respective State) are accused of the same crime until the verification of their right to protection.

Such a crime also implicates the possibility of administrative detention that does not have any trial and is recommended by the EU only as a last resort for reasons of security: this procedure has been proven to obtain as its sole effects the overcrowding prisons and the creation of additional obstacles to integration.

The same discourse is valid towards the refoulement of refugees towards Libya, which violates the principle of non-refoulement under Article 33 of the Geneva Convention, and often [administrators] do not keep count of the diverse backgrounds of detained individuals, turning back potential refugees from the Horn of Africa, as was the case of Hirsi Jamaa et. al in 2009.

Italy has defended itself against these accusations, confronting the issue through bilateral accords with North African countries, first among these Libya, for the repulsion of individuals towards their countries of origin. One should under consideration however that the country, other than being currently instable, does not recognise the right to political asylum and was apprehended by various NGOs under the grounds that it did not uphold the respect of human rights but that there were actually well-known bribery in human commerce.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture have therefore condemned such practices and Italy was sanctioned by the European Court of Human Rights, seeing as it was responsible for sending back such persons to a country who practice arbitrary detention and repatriation. An innumerable amount of individuals are testimonies of migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa that found themselves detained in Libyan prisons under inhumane conditions.

Italy is undoubtedly in a tight position seeing that it serves as the bridge to the rest of Europe; in fact the Dublin Regulation of first asylum contact and the lack of validity of the European agency Frontex make it so that the country is subjected to notable pressure that puts its ability to manage of migration fluctuations and immigration policies to the test.

Italy is undoubtedly in a tight position seeing that it serves as the bridge to the rest of Europe; in fact the Dublin Regulation of first asylum contact and the lack of validity of the European agency Frontex make it so that the country is subjected to notable pressure that puts its ability to manage of migration fluctuations and immigration policies to the test.

It seems however that Italy, for political will and for lack of sufficient support on the part of the European Union, searches to constantly operate within a “gray zone” in which it transfigures its own benefits and the limits of the legality of European directives that it ratifies rather than complying with EU directives.

This is an unfeasable solution, argues the noted sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, “modernity produces immigration.” This is an irrevocable movement that Italy’s political system will have to continue to face and cannot stop, but only regulate.

In all, the declarations of condolences that have stemmed from the past few weeks will have to be followed by political comitments on the part of both Italy and the rest of Europe to produce the necessary changes towards the larger objective of creating a coherent and comprehensive policy that upholds all bases to ensure that incidents such as those of October 3rd occur no more.

Translated from Lampedusa e la dura legge del Mediterraneo