![Image for [Eng] How a Translator Smuggled Goethe and Schiller into Disney Comics](https://media.cafebabel.com/resized-images/ae/e0/2caee78ef7ff74d15dfd12907d4f463a70c8.jpg)

[Eng] How a Translator Smuggled Goethe and Schiller into Disney Comics

Published on

Translation by:

Jacob DaviesA famous woman awoke me to language without ever sharing a word with me. How did Erika Fuchs do it? With her not so exact translations of American Disney Comics. A thank God they were!

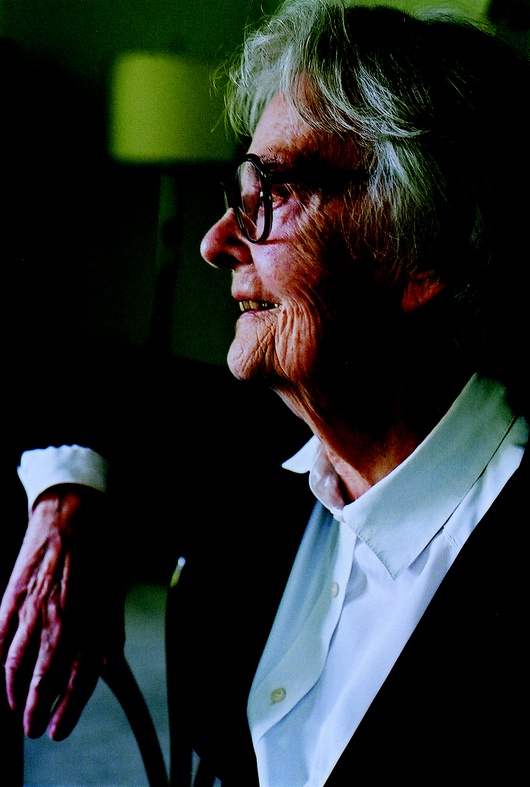

When I was small, there were two books in my parents’ house. “The Football World Cup - 1974” and “The Pope in Osnabrück 1980”. Both were picture books, and both were gathering dust on the shelf beneath the TV. I can also say that a love for language did not come to me in the cradle. Therefore, another woman is answerable - one, I never actually met: Dr Erika Fucks lived at the other end of Germany. In 2005, she died at the age of 98 in Munich. Later, it became clear to me, that she had been palming the young Jens off with the canon of the educated German middle-class.

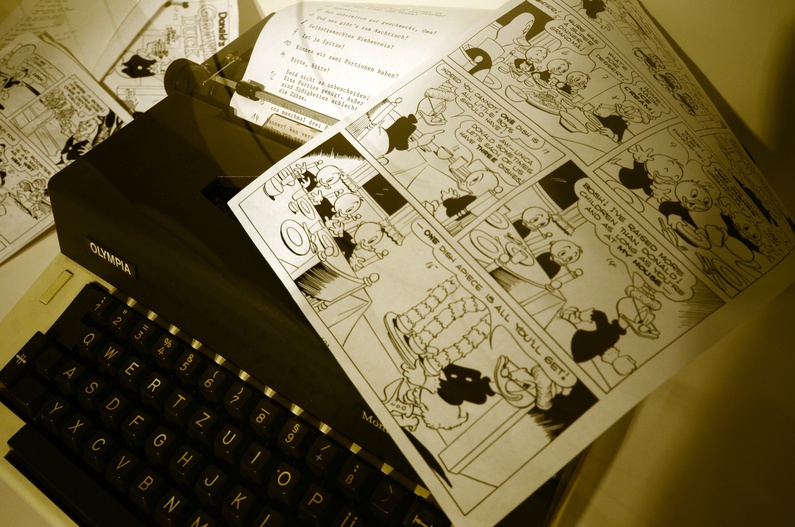

It began long before I was born. In 1951, at the age of 44, the Doctor of Art History was given a new commission: To translate cartoons from the USA.... Cartoons with talking ducks and mice as the protagonists. Almost as bad: The dialogue in these so called ‘Comics’ were squashed into tiny speech bubbles! Who would read such things? Fuchs had her doubts - but accepted it nonetheless. Paid work was hard to come by in the post war era, especially for women who were pushed from the job market by returning soldiers.

It began long before I was born. In 1951, at the age of 44, the Doctor of Art History was given a new commission: To translate cartoons from the USA.... Cartoons with talking ducks and mice as the protagonists. Almost as bad: The dialogue in these so called ‘Comics’ were squashed into tiny speech bubbles! Who would read such things? Fuchs had her doubts - but accepted it nonetheless. Paid work was hard to come by in the post war era, especially for women who were pushed from the job market by returning soldiers.

Translations with imperfections

The newly crowned editor of “Mickey Mouse” didn’t have time for word for word translation. The ‘Hamburger’ became ‘Goulash Soup’, instead of on ‘Halloween’, in ‘Entenhausen’ (literally duck house), people get dressed up on ‘Shrove Monday’ (the high point of Carnival). Otherwise no one in Germany would have understood! Fuchs used the names of places and shops from her own environment; Schnarchenreuth, Kleinschloppen and Bobengrun sound like fantasy names. But they really exist! Just like the real existing Oberkotzau (Fuchs’ home town).

One doesn’t want to come across harsh....

It is more important altogether, that the wordsmith doesn’t care about the original text, but puts quotes from German literature and music into the mouths of Scrooge McDuck, Donald and Co. “It shimmers and sparkles and flickers and burns. A real witches lament” Donald exclaims as The Firebug, swaggering in a mania. And whilst fleeing from their uncle, who wants to shove them in the bathtub, Huey, Dewey and Louie (Tick, Trick and Track in German) solemnly swear the Rütli Oath from Schiller’s William Tell:

“We want to be a single People of Brethren,

Never to wash in danger or distress.

Now and forever.”

Fuchs also changes the characteristic style of the characters: Donald and CO. talk away in the same slang in Duckburg, whilst in the Germanized ‘Duck House’, there are slight differences. The great capitalist Dagobert Duck (Scrooge McDuck to you and I) expresses himself as one would expect from someone of his age and standing. The Safe Breakers babble in Berlin slang, Tick, Trick and Track use teenage talk from the former Federal Republic.

Fuchs also changes the characteristic style of the characters: Donald and CO. talk away in the same slang in Duckburg, whilst in the Germanized ‘Duck House’, there are slight differences. The great capitalist Dagobert Duck (Scrooge McDuck to you and I) expresses himself as one would expect from someone of his age and standing. The Safe Breakers babble in Berlin slang, Tick, Trick and Track use teenage talk from the former Federal Republic.

An Erika Fuchs’ hallmark was the extensive use of cheerful alliterations and ‘Inflektiven’, a German verb form, in which the verb is shortened to its stem, something that is enjoying a renaissance in text-talk. However, the writer does not just use the inflektiv to create onomatopoeia, but also during quiet events. Linguists now talk about the ‘Erikativ’ (the ‘Inflektiv’ used by Fuchs), and no longer just in jest.

A museum for Donald Duck - and the town of Schwarzenbach

Wonder. That is the feeling that greets me as I leave the regional train in Schwarzenbach. Erika Fuchs spent the majority of her life here in the middle of the Upper Franconian plains, where she lived with her husband. When he died in the 1980s, she wasted no time in moving to the more urban environment of Munich. Nevertheless, the townspeople of Schwarzenbach have dedicated a museum to their most famous citizen. The Erika Fuchs Haus became the first comic book museum when it was opened last year. It cost five million euros to design and build. That is a lot of dough for a town with seven thousand inhabitants, especially considering the majority came from donations.

Strolling along the small-town’s main road, leading from the train station, one gets the feeling that Schwarzenbach was once a place that saw better times. There are more than a few empty shops, their yellowing goods staring out of the windows at me.

In fact, the region was once famous for its industry. People would slave away in the iron foundries, welding machines together (for instance in the oven factory belonging to Fuchs Ehemann Günter), weaving materials and firing porcelain. Very little of that remains. Some production methods have become obsolete, others can be done cheaper in different countries. The establishment of the Erika Fuchs Haus is designed to buck this trend. Some shopkeepers say it has made their businesses a real Entenhausen.

Visitors: Newcomers to Comics

15,000 to 20,000 visitors a year have been recorded by those in charge of Schwarzenbach. That does not seem many for a project with such a price tag. “It isn’t about where is best for Germany’s first comic museum, but what the museum could bring to such a place”, Alexandra Hentschel, the museum’s director explained to me. She is proud that by mid-June - ten months after opening - there have already been 19,000 visitors to the museum. There are lots of school classes in the visitor book, but the majority of visitors are older than schoolchildren. Church communities have visited, workers welfare groups have been, local businesses have held company away days here. In Brief: It is not just for diehard comic book fans, but for newcomers too.

My first impression from walking around the exhibition spaces is that they are empty. Pleasantly empty, especially when I imagine how overcrowded such a hipster attraction would be in Berlin or Hamburg, even on a weekday like today. There were only a group of pensioners who were going around at the same time as me, as I walked around the recreated miniature Entenhausen. A ten-minute introductory film explains the most important basics of the comics. This is a must at the start of every tour, in order to understand Fuchs’ legacy to the German language; explains Hentschel. A Disneyland style replica of the Entenhausen would have been far too expensive, she goes on to explain. The solution: an accessible, ‘Pop-Up’, Entenhausen, that recreates the two-dimensionality of comic books as a medium.

Older people love it. Noses curiously peer into the inventor’s workshop of Gyo Gearloose (in German Daniel Düsentriebs - the surname meaning Jet Propulsion), and an old man takes of his shoes and presses his socked foot into Scrooge McDuck’s bed of coins. The replica is not quite so deep that you can “rummage in it like a mole!” But it is perfect for a selfie....

Als

Als

As the group of seniors rounded the corner, I quickly jumped in and made the first ‘coin angel’ of my life. There appears to be a closet adventure capitalist in me after all...

And for hardcore fans?

I find myself in good company. Even constitutional judges have been outed at Donaldists.

Donaldists take the Entenhausen seriously. So seriously that they are scientific in their concern for the Duck cosmos. On video screens, experts such as Mark Benecke, Andreas Platthaus and Christian Wesseli explain the legal system, religion and gender roles in the Entenhausen. It is not that long that comics were seen as ‘dirt and trash’ in Germany, Hentschel explains to visitors. She can well remember a time when well-known magazines, such as Der Spiegel, described comics as ‘opium of the nursery’. It is true, cartoons did not have it easy in the young Federal Republic. Parents feared they would make their children stupid; self-appointed guardians of public morals, openly called for the mass burning of such ‘trash literature’.

In Germany, fortunately, the days when comics were threatened by the burning at the stake are long gone. Therefore, Erika Fuchs’ life story is not told through text laden placards and photographs, rather in cartoons. Just as how Fuchs’ brought Goethe and Schiller to the Ducks of Duckberg, so the illustrator Simon Schwartz has smuggled figures from the Entenhausen into the Fuchsian biography. A policeman, in front of whom a young Erika Reißaus is stood, looks remarkably like Chief O’Hara (In German Kommissar Hunter). And when her father is angry, he literally puffs himself up, in a pose quite reminiscent of a certain feathered tyrant.

Separate from that, the information stands out, joyfully, in the background. Interactive displays allow visitors an insight into the finer parts of Fuchs’ process of ‘reworking’ texts. Wordy sections have to be taken apart and put back together. You can try translating sections of the American texts and then guess the authors of quotes that Fuchs smuggled into the original text. Here, it is worth pointing out one flaw in the museum experience. It is much more fun to embark on this linguistic adventure in a group, than it is to do so alone. But that can be forgiven, because there is a break with the most annoying of all museum rules; the compulsion to remain quiet and reverential. As I slowly make my way to the exit, I hear an old woman in the next room cackle; “We are in the Comic Museum!” and with a further giggle; “You can laugh here!”

___

Ihr habt Lust, Übersetzer zu werden? Meldet euch bei redaktion@cafebabel.com. Wir freuen uns!

Translated from Wie eine Übersetzerin Goethe und Schiller in Disney-Comics schmuggelte