Elisabeth Badinter: are you a mother or a woman?

Published on

Translation by:

Helen CrumptonThe French philosopher is back to theorise that women are increasingly unable to be both a woman and a mother at the same time. How to reconcile both roles?

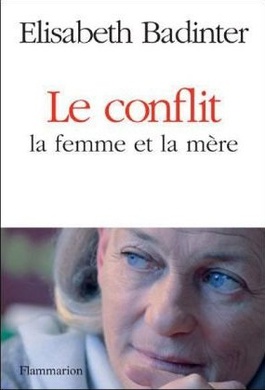

With her book Le Conflit, La Femme et La Mère ('The Conflict, The Woman and The Mother'), which was a bestseller in France amidst its release in February and was recently published in German, the French philosopher, historian and feminist Elisabeth Badinter is heading towards a controversy. But Badinter knows what she is talking about. After all, the 66-year-old respected intellectual had her first child by the age of 22, with two more to follow. ‘I am the average mother, like most women presumably,’ she guesses. In Simone de Beauvoir’s vein she had prepared herself to remove the myths of motherhood and above all of an ‘innate’ mother’s instinct already by 1982 with her book Mother Love: Myth and Reality.

With her book Le Conflit, La Femme et La Mère ('The Conflict, The Woman and The Mother'), which was a bestseller in France amidst its release in February and was recently published in German, the French philosopher, historian and feminist Elisabeth Badinter is heading towards a controversy. But Badinter knows what she is talking about. After all, the 66-year-old respected intellectual had her first child by the age of 22, with two more to follow. ‘I am the average mother, like most women presumably,’ she guesses. In Simone de Beauvoir’s vein she had prepared herself to remove the myths of motherhood and above all of an ‘innate’ mother’s instinct already by 1982 with her book Mother Love: Myth and Reality.

In 'The Conflict' Badinter continues further; in her eyes, being a mother is neither every woman’s natural task nor particularly fulfilling. Children appear as a burden, which is intensified further by groups like La Leche League, which supports the longest breastfeeding period possible for babies; milk substitutions are strongly rejected. Badinter recognises a disturbing change to a naturalistic and traditionalist mother’s image. The fight about milk is simply a synonym for the conflict in which mothers almost inevitably get involved: breastfeeding means a greater tie (in a negative sense) to the child, whereas bottle feeding gives the mother more autonomy. At the end of the day, it comes down to the deciding question of how a ‘woman’ reconciles the roles of motherhood and womanhood.

France: mothers still free to be women

In fact this has been a delicate issue until now, because during all of the improvements in equal rights it is always women who have children. The French pop out children (2.0) more often than in Germany (1.3) for example. Badinter sees a ‘mystical image’ of the German mutter just as the Italian mamma ‘of the devoted but simultaneously all powerful mother’. Here the role of the mother ‘could have been so highly overvalued, that it could have merged completely with the female identity.’ No discourse can come from conflict; a female is either a mother or a woman. France is completely different: ‘20th and 21st century society does not take exception to the fact that children are nursed with a bottle and are put into care very shortly after their birth.’ This very positive image of the ‘Grande Nation’ that Badinter conveys here can be questioned.

In fact this has been a delicate issue until now, because during all of the improvements in equal rights it is always women who have children. The French pop out children (2.0) more often than in Germany (1.3) for example. Badinter sees a ‘mystical image’ of the German mutter just as the Italian mamma ‘of the devoted but simultaneously all powerful mother’. Here the role of the mother ‘could have been so highly overvalued, that it could have merged completely with the female identity.’ No discourse can come from conflict; a female is either a mother or a woman. France is completely different: ‘20th and 21st century society does not take exception to the fact that children are nursed with a bottle and are put into care very shortly after their birth.’ This very positive image of the ‘Grande Nation’ that Badinter conveys here can be questioned.

There was no sign of social acceptance when Rachida Dati, France’s justice minister at the time, left hospital only a few days after the caesarean birth of her first child Zohra in 2009, in order to devote herself to her work - in the eyes of many critics a disservice to women. Feminist Maya Sturduts from the national collective for the rights of women noted that employers could take Dati’s case as an example and therefore exert more pressure on working mothers. However, mothers who have children as a means of staying at home could also feel under pressure.

Sweden: Europe’s model pupil for equal rights

With her analysis of Scandinavian countries Badinter makes up for the critical detachment which is lacking in France at least. In particular Sweden has been considered a model pupil so far: a liberal family policy and a comparatively high birth rate (within Europe) of 12.2 births per 1, 000 inhabitants – in Germany the figure is only 7.9. Compensatory wage increases during parental leave are fortunately being abolished, which can be shared between parents. In 1980, paternity leave was even introduced.

With her analysis of Scandinavian countries Badinter makes up for the critical detachment which is lacking in France at least. In particular Sweden has been considered a model pupil so far: a liberal family policy and a comparatively high birth rate (within Europe) of 12.2 births per 1, 000 inhabitants – in Germany the figure is only 7.9. Compensatory wage increases during parental leave are fortunately being abolished, which can be shared between parents. In 1980, paternity leave was even introduced.

However in reality this has not changed the trend: indeed according to Badinter, 75% of fathers take their paternity leave (ten additional days off on 80% pay) but only 17% take parental leave (at least two months must be taken by the father, otherwise the duration of wage adjustments is shortened). Yet at the beginning of 2009, the Swedish author and journalist Maria Sveland dealt mercilessly with the patriarchal structures and the inequality of relationships in her debut novel Bitter Bitch: Sweden is reportedly more conservative than many would think, as her message would go. Equality is also still a struggle here.

Private life is political

So what can women ultimately learn from Badinter’s work? The Frenchwoman places particular value on the financial independence of women and mothers from their husbands. That is precisely the problem with the book: male and female interests are generally portrayed as antagonistic, although the 36-year-old Sveland shows that it does not work without cooperation.

cafebabel.com meets Elisabeth Badinter

Evidently it is strenuous because it means constantly renegotiating roles in a relationship and defining what you want for yourself. But perhaps one of these days it will be worth it and it will bring changes on a social level. Because private life is political.

Listen to Elisabeth Badinter being interviewed on France Culture radio (French)

Image: main (cc) Schwangerschaft/ Flickr; German poster 'dream woman' (cc) Admiralspalast Berlin/ Flickr; in-text woman at Swedish gay pride (cc) CharlesFred/ Flickr/ charlesfred.blogspot.com

Translated from Elisabeth Badinters 'Konflikt': Mutter oder doch eher Frau?