Elections, elections: buy a vote for 50 euros in Bulgaria

Published on

That's how much a vote can be worth in some areas of Bulgaria. Shortly after the country’s entry into the EU, in the 2007 national election, the problem was so prevalent in local elections that Brussels became alarmed

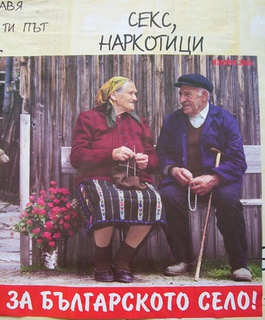

While still less developed than its western counterparts, Sofia resembles most other modern eastern European capitals. Walking around you catch frequent wifi signs, stores with the latest fashions and young twentysomethings gathering at bohemian watering holes. But this is the poorest country in the EU. In more local, rural areas just 15 miles outside the capital, Bulgaria wrestles with its biggest problems: organised crime and corruption.

Feudal lords

As in the rest of Europe, EU funds in Bulgaria are distributed locally, so often it is corrupted small municipalities that decide where to spend the money. The EU commission halted the 500 million euros in aid in summer 2008, no longer feeling it could guarantee its ethical spending. With the next national elections coming up this summer, possibly on the same day as the European parliament elections (4-7 June), democracy advocates are scrambling to make sure the country isn’t embarrassed by tales of vote-buying again.

As in the rest of Europe, EU funds in Bulgaria are distributed locally, so often it is corrupted small municipalities that decide where to spend the money. The EU commission halted the 500 million euros in aid in summer 2008, no longer feeling it could guarantee its ethical spending. With the next national elections coming up this summer, possibly on the same day as the European parliament elections (4-7 June), democracy advocates are scrambling to make sure the country isn’t embarrassed by tales of vote-buying again.

Vote-buying has existed to some degree in many countries of the former eastern bloc, but in Bulgaria it’s become an increasingly organised activity. ‘Vote-buying was once limited to very poor districts,’ says Georgi Stoytchev, executive director of the Open Society Institute in Sofia. ‘All of a sudden, this practice started affecting very rich communities.’

‘The mafia uses local parties to control the cities and is now preparing to buy the next election’

Local business and organised crime figures buy their way to power and award themselves contracts and funding from the municipalities. ‘They behave like a feudal lord,’ says Svetlana Lomeva, executive director of the Bulgarian School of Politics. ‘There are now around 400 total registered parties in Bulgaria, because so many of them are forming their own parties in order to put themselves in office.’ ‘It allows them to act with impunity,’ Bulgarian MP Maria Coppone agrees. As a vocal member of the centre-right opposition to the socialist government, she says this has much to do with the breakdown of the main political parties in Bulgaria. ‘The mafia uses local parties to control the cities,’ she says, ‘and is now preparing to buy the next election.’

How it works

Cutthroat businessmen can ‘make’ employees vote for them either by promising them a raise or threatening them with demotion. Individuals not directly on the payroll can be bought fairly easily from anywhere between five to fifty euros, depending on the wealth level of the local population, says Vanya Kashukeeva-Nusheva, programme coordinator for Transparency International in Sofia. These can then prove their vote by taking a mobile phone picture of their filled-in ballot. Or, the vote-buyer may provide the individual with a filled-in ballot, in exchange for an empty ballot to be brought back on election day and eventual payment.

Cutthroat businessmen can ‘make’ employees vote for them either by promising them a raise or threatening them with demotion. Individuals not directly on the payroll can be bought fairly easily from anywhere between five to fifty euros, depending on the wealth level of the local population, says Vanya Kashukeeva-Nusheva, programme coordinator for Transparency International in Sofia. These can then prove their vote by taking a mobile phone picture of their filled-in ballot. Or, the vote-buyer may provide the individual with a filled-in ballot, in exchange for an empty ballot to be brought back on election day and eventual payment.

Usually a vote-buyer will buy a bulk of votes in the thousands in an individual locality. It’s easy to verify who has voted what by checking the way that municipalities voted, since votes are counted locally and the results are published. ‘It’s very difficult to persecute,’ says Stoytchev. ‘Some businessmen simply increase the salaries of people who voted for him, or pay voters as if they were part of the campaign. During the last election one local businessman in the city of Sandanski – who basically runs the town - was caught buying votes,’ adds Lomeva. ‘He was fined 2,000 leva (1, 000 euros) and is still in office.’ Major parties are also involved in vote-buying, but at a local level. ‘Their local organisations are completely out of their control,’ says Lomeva, ‘with closer ties to local business than to Sofia.’

Root of the problem

Ironically, though the EU is now demanding reform on the issue, it itself had a hand in creating the problem. Because EU funds are distributed locally, during the accession process local municipal positions suddenly became very important because they were the ones allocating the money. At the same time, the real estate boom of the past several years made local positions very important because they controlled who received building permits.

Ironically, though the EU is now demanding reform on the issue, it itself had a hand in creating the problem. Because EU funds are distributed locally, during the accession process local municipal positions suddenly became very important because they were the ones allocating the money. At the same time, the real estate boom of the past several years made local positions very important because they controlled who received building permits.

Transparency International’s Kashukeeva-Nusheva says the collapse of people’s faith in the major political parties is largely to blame for the increase in vote-buying. ‘There is no longer a feeling that the political parties are representing the people’s interest,’ she says. ‘Voter turnout is falling, so people who do vote gain more and more influence.’ If people believe the national government is ineffective and useless, they will naturally be more amenable to selling their ‘worthless’ votes. In recent surveys, less than 5% of Bulgarians have said they would consider that. Yet the perception amongst Bulgarians is that the number of people actually selling their vote is much higher.

NGOs work feverishly

Transparency International and Open Society have drafted an ‘Integrity Pact’. Signed by most of the major political parties, it promises to introduce internal party rules adopting a zero tolerance policy toward vote buying, and it pledges to create a government campaign monitoring body with sanctions. It also calls for increased transparency in party financing and the establishment of a public register of campaign donors, who in the future would only be able to make donations by bank transfer rather than cash. 'If a party has access to a lot of ‘shadow money,’ they can’t buy advertising with it because then they would have to declare it,' says Stoytchev. 'So they use it to buy votes instead.’

The most controversial aspect of the pact – and the provision that has kept the ruling coalition of socialists and the Turkish minority party from signing it – is its call for vote-counting to be moved from local polling stations to regional counting sessions, so that here is less way of knowing if bought votes have actually been cast. ‘We can’t stop people, but we can limit them,’ says Stoytchev. ‘We want to say, go ahead and take the money, but then go ahead and vote how you want, because the vote-buyers won’t be able to tell.’

The most controversial aspect of the pact – and the provision that has kept the ruling coalition of socialists and the Turkish minority party from signing it – is its call for vote-counting to be moved from local polling stations to regional counting sessions, so that here is less way of knowing if bought votes have actually been cast. ‘We can’t stop people, but we can limit them,’ says Stoytchev. ‘We want to say, go ahead and take the money, but then go ahead and vote how you want, because the vote-buyers won’t be able to tell.’

Both Stoychev and Kashukeeva-Nusheva say that without the socialist signature, the integrity pact will lack teeth, and that the provision for creating regional counting centres is non-negotiable. In the meantime, Maria Cappone says politicians can help by making sure people know that selling your vote is not only a crime - it is also harmful to your country. Her ‘clean at hands’ campaign calls for a complete reform of the national government.

In the end, Bulgarian politicians themselves must root out the corruption in local government. ‘Brussels can have all the monitoring and reports they want,' she says. ‘But in the end we must do our job here. The people must trust us again.’

Read the official babelblog by our team in Sofia