East-West divide

Published on

Translation by:

lindsey evans

lindsey evans

Since the Roma are legally defined as a minority in Europe, officially they benefit from a protection of their rights. However, the way that laws are applied varies within the Union

Gypsy, nomad, traveller… Let’s call them ‘Roma’ from now on. It’s more polite. The international community adopted this term in the 1990s, a period when there was a proliferation of legislative initiatives aimed at protecting this minority. However, the Romany issue hasn’t suddenly emerged mysteriously from Brussels, but has haunted Europe since the Middle Ages. A travelling people - nomads by virtue of the fact that they are not allowed to put down roots anywhere - the Roma feel the full force of European policies governing the settling of populations and the regulation and tracking of human movement. Outside the law, as a result of the existence to which they have been condemned, the Roma are pushed to the fringes of society.

The Copenhagen criteria

If the Romany question is resurfacing today, this is no doubt thanks to the Council of Europe and the sacrosanct Copenhagen criteria established in 1993 which determine the minimum political requirements that EU candidate countries should meet: democracy, the rule of law, respect for human rights and protection of minorities. The candidate countries of Central and Eastern Europe have, as a result, been obliged to develop specific policies, often instilled with a sense of the well-meaning and politically correct.

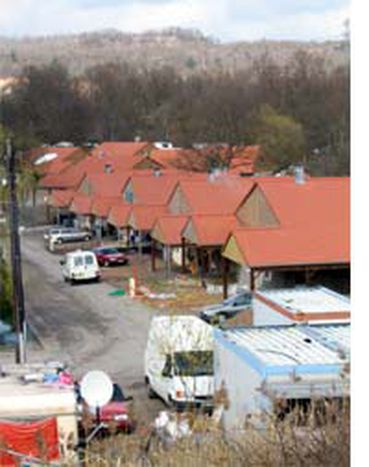

The contrasting examples of Slovakia and Hungary illustrate these developments. In 1993, the brand new Republic of Slovakia had to balance building a national identity with observing the new criteria of good governance, including the protection of minorities. It was written into the Slovak Constitution that international ruling on this subject would take precedence, but leaders gradually realised the need for a specific policy beyond that of mere non-discrimination. Despite the improvements, however, Roma still lose out: the Slovak Commissioner for the Romany question has not been allocated enough funding, the unemployment rate among Roma communities is skirting 100%, and it is impossible for them to pursue higher education in their own language…

In Hungary, the issue was handled differently. Champion of ‘multi-nationality’, the home of the Magyars was the first country in the world to recognise the rights of minorities. It even served as an inspiration to the Council of Europe. The Hungarian Constitution recognises 12 official minorities, which enjoy the most extensive collective rights in Europe: access to education and cultural activities, representation in municipal councils, and integration into the national political structures. In addition, a post of Commissioner for Minorities was created, and a precedent was set in the Constitutional Court in favour of positive discrimination in voting law.

If Hungary has developed such a formidable judicial and political arsenal in favour of its minorities, this exists also to guarantee fair treatment of her own diaspora. But the Roma have no state, no country, and therefore no real means of reciprocating. As ever, the Roma are the charity cases in these positive measures. In Hungary, as everywhere else, they are more often victims of police violence, benefit less from social policies, and are not considered as ‘respectable’ as other social groups, even other minority groups.

The self-satisfaction of the West

What about Western Europe? In France, Roma are confined to the category of ‘travellers’. Since the passing of a law on 5 July 2000 relating to the integration of travelling peoples and their living conditions, the way in which Romany Gypsies are received in schools and settled communities should have improved. But unfortunately, social policies on housing, and all that follows on from that, do not extend to travellers. Case closed.

In other Western countries of the Union as well, Roma constitute a misrepresented and little protected minority. A few consultative bodies have been set up here and there in Austria and Belgium. But, whereas there is a dedicated ministry in the Netherlands, in Denmark and Sweden the protection of Roma depends on a mediating body. Finland has just proposed a consultative European forum for the Roma, which would allow them to acquire a transnational visibility more compatible with defending their interests. The eternal problem of collective rights, which scares the life out the EU member states, is being put back on the table. Hopefully, this means that Europeans will finally have to come round to the idea of accepting the propositions made by the European Council in 1990 regarding these rights.

For the moment, Eastern Europe remains the most active in trying to guarantee Roma rights. At the beginning of February, representatives of eight states of Central and Eastern Europe convened at Sofia to commit firmly and mutually to non-discrimination against Roma. They should have invited ‘Old Europe’ – it wouldn’t have done her any harm. Over here, with no Copenhagen criteria to satisfy, the Commission does not really look into the treatment of Roma. Especially as the last UN Development Programme report, the biggest ever compiled on the Roma’s situation, only took into account their treatment in Eastern Europe. This is regrettable, because in Old Europe the Roma are gypsies and travellers first, people second.

Translated from L'Europe de l'est fait plus d'efforts