Doris Lessing: stick your Nobel Prize

Published on

Translation by:

Daniel G. RossEnglish writer Doris Lessing, 87, won the 2007 Nobel Prize for being an 'epicist of feminine experiences'. But the literature prize lacks the lustre it once had, often charged with being less than impartial

September 2007 marks the centenary of the death of French writer Sully Prudhomme. A labourer turned poet and later academic, Prudhomme was also the first Literature Nobel Laureate. It is a safe bet to say that few people have heard of him. Perhaps they are more familiar with one of his unlucky competitors, rejected by the academy in favour of Prudhomme in 1879 and now counted among the greats: Leon Tolstoy. The Russian author was considered too political and the jury prefered to reward the author of Stances et Poèmes '(Stanzas and Poems', 1865).

The history of the Nobel Prize in Literature began with what is now seen as an injustice. Today the list of laureates is peppered with similar ‘errors’, from a preponderance of the illustrious forgotten - such as Prudhomme - to a few unforgivable omissions – think Emile Zola or Franz Kafka. In addition to the prestige conferred by the prize, laureates receive more than ten million Swedish Crowns (1.1 million euros). But that hasn’t stopped certain recipients from declining the award or stirring up scandal.

The history of the Nobel Prize in Literature began with what is now seen as an injustice. Today the list of laureates is peppered with similar ‘errors’, from a preponderance of the illustrious forgotten - such as Prudhomme - to a few unforgivable omissions – think Emile Zola or Franz Kafka. In addition to the prestige conferred by the prize, laureates receive more than ten million Swedish Crowns (1.1 million euros). But that hasn’t stopped certain recipients from declining the award or stirring up scandal.

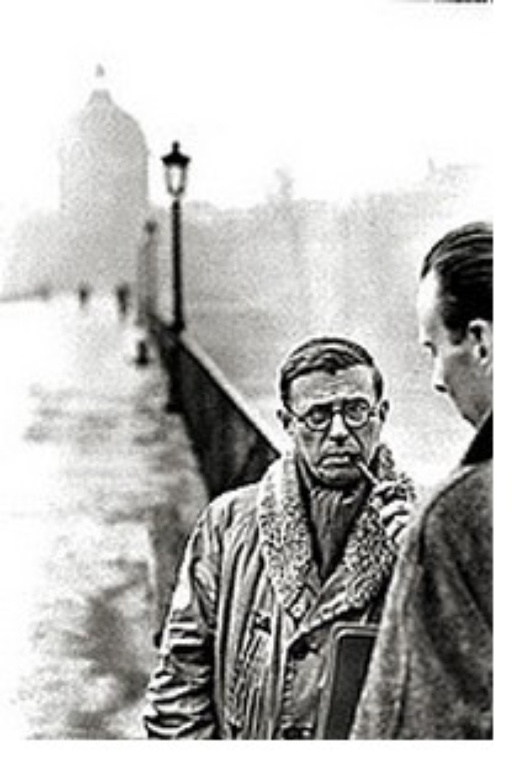

1964: the case of Sartre

Not wanting to ‘play the ape in Stockholm’ in the words of Simone de Beauvoir, or to see himself ‘institutionalised’, Jean-Paul Sartre wrote presciently to the Academy to ask its members not to bestow the prize on him, ‘not in 1964 nor later’. His demand was ignored: the final decision had already been taken to honour the father of existentialism for his memoir Les Mots ('Words', 1964). Upon learning that he had won, he wrote a second letter to the Academy to explain his refusal. Few of his contemporaries understood his refusal of such a tidy sum, and newspapers would accuse him of a publicity stunt.

2004: Elfriede Jelinek, the unwilling Austrian

Juror Knut Ahnlund accused her of having written nothing but a ‘heap of texts’, and later left the Academy rather than go along with the decision to honour her ‘pornography’ with a Prize. Jelinek, a feminist, radical leftist, outspoken critic of Austria and the author of The Pianist (1988), did not attend the ceremony the night she won. Fresh scandal. Instead it was her publisher who spoke in her place, recognizing that the award 'would allow her to work in perfect independence.’

Juror Knut Ahnlund accused her of having written nothing but a ‘heap of texts’, and later left the Academy rather than go along with the decision to honour her ‘pornography’ with a Prize. Jelinek, a feminist, radical leftist, outspoken critic of Austria and the author of The Pianist (1988), did not attend the ceremony the night she won. Fresh scandal. Instead it was her publisher who spoke in her place, recognizing that the award 'would allow her to work in perfect independence.’

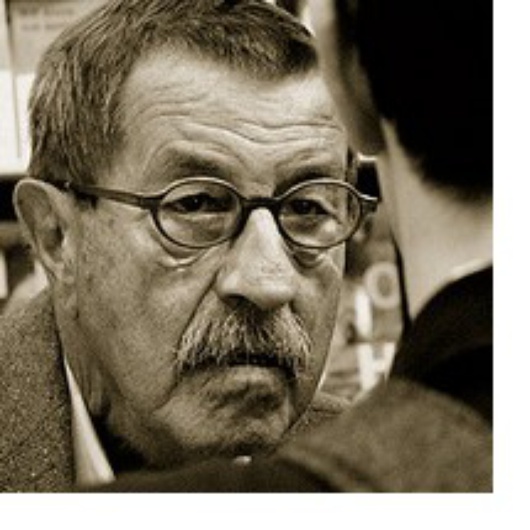

2006: Günter Grass, formerly of the SS

Last year German writer and 1999 laureate shocked the world of literature when he revealed that at the age of 17 he joined the elite of the Germany army, the Waffen SS. Peace Nobel Laureate and Pole Lech Walesa demanded that Grass return his award of honoured citizen to the Polish city of Gdansk. The Nobel Foundation made it known that it would not expect the return of his Prize. Nonetheless, Grass’s official biography on the website of the Academy is no longer being updated.

Last year German writer and 1999 laureate shocked the world of literature when he revealed that at the age of 17 he joined the elite of the Germany army, the Waffen SS. Peace Nobel Laureate and Pole Lech Walesa demanded that Grass return his award of honoured citizen to the Polish city of Gdansk. The Nobel Foundation made it known that it would not expect the return of his Prize. Nonetheless, Grass’s official biography on the website of the Academy is no longer being updated.

Today, the Nobel Prize is faced with new accusations of straying from the impartiality envisioned by its founder. History shows that the Academy is partial to Europeans. No less than a quarter of the prizes awarded to date have gone to writers who work in English. Thirteen Francophone authors have been honoured, representing around 13% percent of the total. German speakers are not far behind, at 12% - thus three European languages account for half of all laureates. In comparison, China can claim only one laureate, and of the four Africans who have won the Prize, three write in English (Coetzee, Soyinka and Gordimer). As well as being Europhile, the Academy tends to privilege male writers over females: to date there have been only ten female laureates.

In-text photos: Jean-Paul Sartre (tinajankulovski/ Flickr), Günter Grass (Habakuks Ansichten/ Flickr), Elfriede Jelinek (Isaak Mao/ Flickr)

Translated from Nobel : j'en veux pas d'ton prix