Don't call Aline an eighties band...

Published on

Translation by:

Georgia NewmanAfter having climbed the stairs one by one, lead singer Romain slumps onto the sofa of the cosy loft, evidently pleased that this interview is not being filmed. Guitarist Arnaud has also cottoned on, as he spreads his long legs out on the side table.

Two of the members of the band from Marseille look on nonchalantly, observing what we are about to offer them to wash down the large media dose they have already been injected with

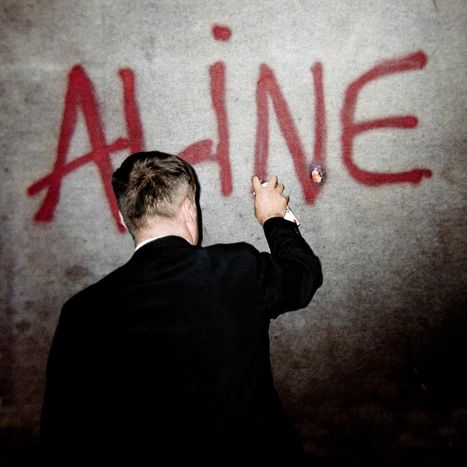

January 2013. In Paris, the sky is dark and the clouds are low. Outside, the City of Light illuminates only the multicoloured signs of the fruit and vegetable vendors. As is typical of popular bohemian neighbourhoods such as the 20th arrondissement of Paris, we slink between two of these shops and are thrust into a courtyard, the kind that can only still be found in this suburban area of the capital. Dried up plants twirl around in the glacial wind, while yellow wooden chairs are randomly placed on either side of the narrow alley. At the end of the alley, RomainGuerret, the band’s main songwriter, is smoking a cigarette and looking relaxed behind his black sunglasses. Buried in a black duffel coat covered in badges, he invites us to follow him for what will be the last interview in a long day of promotional activities.

Look at the sky

It must be said that, since the release of Aline’s first album, Regarde le ciel ('Look at the Sky'), the band - which hails from the southern French city of Marseille - has been caught up in something of a whirlwind. French newspapers and magazines such as France 5, Technikart, Le Figaro, Télérama, Les Inrocks and even L’Huma have all flocked to clamour over their ambient pop. 'We’re almost surprised to see that the band is attracting so much attention,' says Arnaud Pilard. Romain, who has taken off his coat in favour of a denim blazer, scratches his head, suddenly letting an unlikely grey tuft of hair spring free. 'It’s cool, it’s expanded our audience. We feel like we’re coming out of our indie shell a little. Also, 99% of the reviews are positive,' he points out.

By way of explanation for this sudden media appetite for the band, they point the finger at a current trend - 'the famous new French scene'. In 2012, the major successes of the 'Made in France' movement were found in song, with bands such as Lescop and La Femme, and compilation projects promoting French artists. The songs were sung in French, earnestly, in homage to forebearers who were already thinking that the English language was starting to kick French in the balls from the eighties onwards. In early 2013, Aline's star took off. Like a magnet, one article after another typecast the band as 'part of an eighties revival'. 'Does it bother us? Well yeah, it’s annoying. Also, the eighties revival makes me laugh. It lasted fifteen years.' Romain sounds irritated, well versed on the theoretical definition of the eighties.

When everything was 'messed up'

'Aline was the imaginary home city of Young Michelin in the biography that I made up,' Romain explains. The band used a ‘caphchta’, a tool which essentially generates names automatically, to come up with the name Young Michelin. The thing that most winds up our singer is that Aline did not expect the powerful comeback of the theremin. Romain has made music 'seriously, for about a decade', and has 'always composed in the same way'. 'I never wanted to sign up to a ‘vintage’ revival,' he says. The story behind this is that in the times when he was known as Donald (his father gave him this second name), he was slogging away in the almost eponymous band Dondolo, whose two albums released under this name (Dondolisme, 2007, and Une vie de plaisir dans un monde nouveau, 2008) bear little or no resemblance to Aline’s first opus.

'Aline was the imaginary home city of Young Michelin in the biography that I made up,' Romain explains. The band used a ‘caphchta’, a tool which essentially generates names automatically, to come up with the name Young Michelin. The thing that most winds up our singer is that Aline did not expect the powerful comeback of the theremin. Romain has made music 'seriously, for about a decade', and has 'always composed in the same way'. 'I never wanted to sign up to a ‘vintage’ revival,' he says. The story behind this is that in the times when he was known as Donald (his father gave him this second name), he was slogging away in the almost eponymous band Dondolo, whose two albums released under this name (Dondolisme, 2007, and Une vie de plaisir dans un monde nouveau, 2008) bear little or no resemblance to Aline’s first opus.

Romain, therefore, was already producing a range of simple, uncluttered pop, similar to that of The Smiths, The Byrds, and more or less everything that English indie pop label Sarah Records was producing. 'The idea is to go to the heart of it, to purify and simplify things by forcing yourself to be consistent and to only keep what is absolutely essential,' he explains. 'It’s a very focused, clear approach,' adds Arnaud, whose serious disposition glints through Aline’s record.

'This record tells the story of two years in a slump - disillusion, worry in the face of the future. I fucked everything up'

After Dondolo came Young Michelin, a band which received a swift puncture to the tyres when the eponymous tyre company were not willing to share their brand image with the neurotic rockers. This was at the end of 2011 and, paradoxically, at the end of their troubles, because Romain has it that 'everything before that was messed up'. He has long worn the hat of the tortured soul, born in the wrong time. However, if anyone looks closer at even a few of the lyrics on Regarde le ciel, they will notice that Aline’s songs deal with highly contemporary subject matters such as disenchantment, the financial crisis, and the recession… 'This record tells the story of two years in a slump - disillusion, worry in the face of the future. I fucked everything up, everything went balls up, it was really messed up,' Romain exclaims.

However, the genius of the record lies in its representation of this negativity. where its pessimism is dressed up in a truly great sound. In short, with Aline, the sound of unemployment and pennilessness is sweet. Romain looks up at the sky: 'I am constantly searching for beauty, wherever it might be: in nature, the seasons, the sky, the clouds, my daughters or my friends. I feel a little like a poet observing the world.' If Aline’s success has resulted in his band becoming a 'full-time job', this songwriter will always tune his guitar to the journey, into the unknown. Somewhere else. And then it would be goodbye, cruel world.

Find more information about Aline's French tour here

Images: main and in-text © Matthieu Amaré/ whole group photo courtesy of © Aline official facebook page/ video (cc) Alinepopband/ youtube

Translated from Aline : adieu, monde de merde