Digital art: Turning traditional art on its head for good

Published on

Translation by:

Odile Michely

Odile Michely

It’s hard to know exactly what digital art is; it’s strange, obscure and confusing. Yet throughout the history of art, it is by far the most tangible art form in our daily lives. And I’m convinced it will soon take over our cultural institutions.

I first heard about digital art when I was in an art history class. I immediately thought that digital artists were a group of esoteric and geeky people. I had never once crossed paths with this kind of artist throughout my countless museum visits, and I came to the conclusion that digital art was a ephemeral movement that took place between the 1940s and the 1980s. It was a temporary fad, like many other has-beens. I had absolutely no idea how diverse this art form was, nor did I know of any collections in international cultural institutions dedicated to it.

David Hockney, cotton candy and an iPad

As I dissect the programmes of cultural spaces in Paris, I realise that three of the biggest museums are dedicating their exhibition spaces to digital art. The Palais de Tokyo gave a carte blanche to the famous French artist Camille Henrot, the Fondation Louis Vuitton opened its top floors for contemporary artists like the American Ian Cheng, and the Centre Pompidou – along with its exhibition of David Hockney’s work – is projecting an artwork created entirely on an iPad.

I realise that all three digital artists have one thing in common: the use of video. Quick to draw conclusions, I turn to my digital art professor Clément Thibault and say something along the lines of “I don’t understand why, in the world of art theorists, we have to complicate everything. Why can’t we just talk about video art instead of confusing everyone with this notion of ‘digital art’?” Keeping his calm, he suggests that I attend the Biennale Némo to get a more “balanced idea” of what digital art really is.

After doing some research on the Internet, I learn that the event is actually the international biennale for digital arts. For its second edition, shit got real: six months of exhibitions from the 4th of October 2017 until the 18th of March 2018 with 130 meeting places in about 50 different locations across Île-de-France (the region around Paris). A little confused and intimidated, I choose to stay in my comfort zone and head to the Centquatre for an exhibition called Les faits du hasard (“The facts of chance” in French, ed.) in the 19th arrondissement in Paris.

It’s grey outside and my motivation starts to stagger. But the atmosphere of the Centquatre quickly snaps me back to reality. I pass through the hall where many people are dancing, singing and juggling, and eventually reach the exhibition. For a good minute, I thought I was in the wrong place. A giant cotton candy machine spurts out edible threads in the air. In the distance, people are running on a platform to make a giant object dance. I take a look at the brochure, which is rather sober and conventional, quite fitting for a contemporary art exhibition. Still, I feel as though I’m in an amusement park. “Excuse me, is this the Les faits du hasard exhibition?” I ask the father of a family. “You’re at the heart of it all, young man!” he replies.

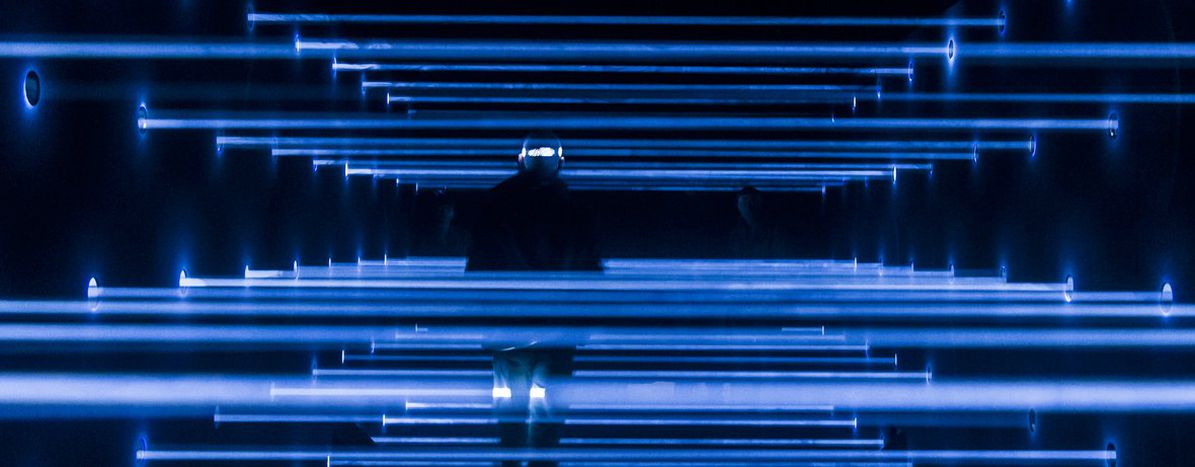

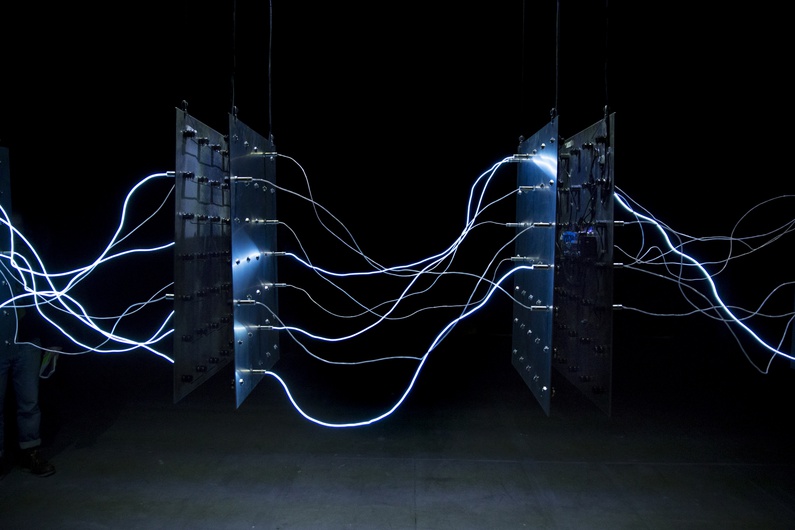

I’m not used to seeing so many active spectators in an art exhibition, as I have always been accustomed to a contemplative silence in this kind of place. From one surprise to the next, I encounter bright choreographies that seem random and an installation of metallic rods connected to something that looks like prairie in Minnesota, bouncing around in the wind. I stop at the aquaphoneia, created by two multidisciplinary artists Michael Montanaro and Navid Navab that, like its name suggests, transmutes sound waves through water in the air. You whisper a sentence in a horn and you observe the transformation of water into air. Evaporation catalysed by words, basically. Here and there, people are enjoying themselves and trying to figure out how the different installations work. Some are asking other visitors for instructions, while others turn to their smartphones for help.

So turns out that digital art goes well beyond videos. Still, my professor forgot one important thing: how can we define what digital art is? It’s too difficult to come to a conclusion after my visit at the Centquatre. Too many variations, too diverse.

“Dada”, digital art’s first word

Intrigued by my experience at the Centquatre, I turn to my professor to learn a little more about digital art. He tells me that, while the first international biennale for digital art only took place in 2015, the concept itself dates back to nearly a century ago. The dadaists were the first to incorporate digital art in their movement. Artists like Man Ray or Marcel Duchamp created an aesthetic system that combined various artistic mediums (collage, sketch, painting, ready-made), while simultaneously giving way to chance (hence the title of the exhibition at the Centquatre). While traditional schools emphasised a complete mastery of mediums, dadaism assigned more freedom to the creation of art, allowing chance to become part of the creative process. That is how digital art became a product of the dada movement.

When I ask Clément Thibault a week later to give me a symbolic date for when digital art emerged, his response is nuanced: “Scientists and artists in the late 1940s and early 1950s who were influenced by Norbert Wiener and who were interested in cybernetics could be considered the first ‘digital artists’.” Artists like Nicolas Schöffer and William Grey Walter stand out, even if they created analog works. Digital art as a visual art form was born without a name, and was first conceived by engineers such as Ben Laposky, Frieder Nake and Bells Labs.

It’s not until the 1960s that these works left the world of engineering and became recognised as artworks, mixing performance, music and installations. This shift came with the development of Experiments in Art and Technology, and in a sensational way, what would soon be characterised as digital art broke free of traditional artistic works. “For a long time, technology and contemporary art were two separate worlds; they formed two parallel universes,” Clément Thibault explains.

Digital art distinguishes itself from traditional art in three ways. The first is manifested by the creation of multimedia works. Then, digital art challenges the way we think of an artist. Far from being solitary geniuses like Da Vinci, digital artists often work in groups with programmers and engineers. And lastly, digital art is interactive – something necessary for this art medium to flourish. The Centquatre exhibition wouldn’t have been much of a success without its enthusiastic visitors, for example. The potential of digital art lies in its participatory aspect. This notion is so widespread that when I ask Clément about the specificity of digital art, he promptly replies: “What distinguishes digital art from traditional art (painting, drawing, sculptures) is that it’s interactive and it’s able to adapt to the environment and participants.”

Instagram, Facebook and even Periscope art

Thanks to the Internet, everyone has had the right to speak out since the early 1990s. Everyone has access to culture, to different skills. Back in the day, one of the convictions of digital art was to break with the exclusionist and reactionary world that surrounded traditional cultural institutions. That is why the Internet quickly became an artistic medium, a creation tool, but also an exhibition platform.

The border between the artist and the viewer has never been so porous. Most of the time, digital art uses mediums and instruments known by everyone. “The digital world is omnipresent today, so it’s only normal that artists use it more and more, and that the general public grow more used to it,” Clément Thibault underlines. That is how Instagram, Facebook and even Periscope art emerged. Video games also inspire many artists with their fictional universes and immersion techniques. Virtual reality is a gold mine for digital art explorations as well, and it’s very likely that in the future, every single museum will have a CAVE (Cave Automatic Virtual Environment) – entire rooms dedicated to virtual simulation.

Digital art is close to the public on several levels, and, unlike traditional art experiences, usually combines different senses. This originality is in stark contrast with traditional art forms, which is why digital art has a hard time being acknowledged by cultural institutions, galleries or art collectors. Besides, it is quite difficult for digital art to be maintained. Keeping software update is complicated and costly, and the artworks are not easily reproduced since they are often a series of computer codes. For their part, artists have long rejected the traditional institutional imperatives of “exclusivity”, a concept that goes entirely against the web 2.0 principle of sharing and community-based openness.

A programmed conquest

So was the Némo Biennale an exception on an international level? Not at all. Since the early 2000s, digital art has seduced numerous renowned institutions across Europe, such as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, MEIAC in Spain and the iMAL in Brussels. Digital art festivals are also becoming more and more popular, from the Némo Biennale to Elektra in Montreal, Cinématics in Brussels and Transmédiale in Berlin. In 2012, more than 437 digital art festivals were listed in the digital festivals guide.

Moreover, in France, the budget assigned to digital art projects has considerably augmented in recent years, from 75,000 euros in 2006 to 226,000 euros in 2011. Art education institutions like the écoles supérieures d’art in Cambre, Brussels, Namur and Tournai now offer specialised programmes to train future digital artists. Yet the number of digital artists remains extremely low. Only some 70 digital artists were officially recognised by the Ministry of Culture in 2013, while the number of recognised painters already reached 9,000 in 2005.

Nevertheless, digital art is clearly gaining ground in the world of contemporary art. “Today, all the artists use digital tools at some moment in their creative process, even if it’s just for research. Recently, we have been talking a lot about David Hockney’s iPad paintings. Things are blending with one another to a point that it is now necessary to ask if there’s a digital art that’s not also contemporary art. Some critics prefer to refer to it as the ‘digital coefficient of art’,” Clément Thibault explains.

To a certain extent, digital art also comes to break the sometimes snobbish side of traditional institutions. Everyday interactivity give visitors a new cultural experience, one that’s more diversified and educational. You’ve got to admit, it’s pretty cool to think that the future of art looks something like a giant cotton candy machine, right?

Translated from L’art numérique : le beau futur de la culture