Democratic index for Europe

Published on

After Eurobarometer and the ‘Index of Happiness’, a new index launched by a British think tank on 31 January aims to ‘measure’ democracy in 25 European countries – and get Europe's citizens to customise their own indices online. Interview

‘You almost have to throw a rock through a window to get attention for Belgium.’ Teacher Gerrit Six’s reason for trying to sell the kingdom of Belgium for 14 million US dollars on ebay in September 2007 was a media tactic, and one example of Europe's citizens acting out against their disillusionment with politics.

‘There is a growing distrust with politics and politicians,’ agrees a bubbly Jacki Davis, head of communication at the European Policy Centre in Brussels. ‘I was struck that the 2007 Eurobarometer survey from the European commission showed 61% think their country’s voice comes before their own (35%). People listen to their national politicians.’ The EU is doing OK; the same survey shows that more people trust the EU (48%) than their own governments (34%). ‘But Europe's leaders should not just consult people when there is a treaty that needs ratifying,’ criticises Davis.

‘There are lots more signs that people are demanding – and getting – more say over the decisions that affect their lives,’ says Kirsten Bound, researcher at Demos. The independent, not for profit think-tank carries out research on a wide range of social and public policy issues and launched the ‘Everyday Democracy Index’ (EDI) on 31 January. She answers our questions below.

What is the EDI?

The EDI ‘measures’ the democratic health of countries using data from 25 member states. We didn’t collect our own data in each country, but analysed a number of up to date existing reputable sources.

To find out how trends pan out across Europe, we measure people’s sense of empowerment in their everyday lives – at work, within their families, in the public services they receive – as well as at the ballot box. The countries which do most to empower people in their everyday lives are also the ones that have the healthiest levels of formal political engagement. Countries lower on the list, like Slovakia and Romania, are generally the former communist countries that are new to democracy.

Is it just another index?

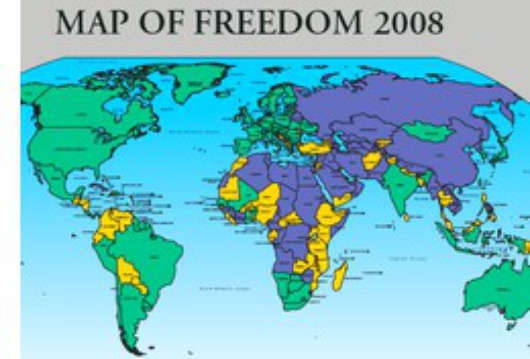

There are several indices of democracy. The most famous is probably US-based NGO Freedom House’s annual ‘Freedom in the world' survey. But these tend to be very black and white, asking is a country a democracy or not? That’s fine if you are mainly interested in the difference between Belgium and Burma. (See their response below this interview.)

The EDI is more useful if you are interested in the differences between Finland and France. If you want to understand what the experience of democracy is like in countries like the EU member states – which all have the basic mechanisms for free and fair elections – then you need a finer grained approach.

How do you 'measure people’s sense of empowerment in their everyday lives’?

The basic idea – that it is only by empowering people in their everyday lives that you can change the way they feel about politics – is to find ways of comparing how countries do that. We want to start digging down into what’s really behind how countries perform.

For example, there is an extremely close relationship between how countries score on the EDI and overall measures of happiness and life satisfaction. There is a large gap between leading democracies in Scandinavian countries and the UK, which polls 9th after France and Germany. So is it that democracy makes you happier? Or that happiness makes you more democratic?

How would an EDI look if it was kicked off by researchers in eastern/ central Europe - not organised from a western Europe research perspective?

It would be really interesting to find out. One of the things we want to do differently is to involve the public in helping us refine it. We have built a website at www.everydaydemocracy.co.uk where users can tell us how they would have done it differently. They can see how we put the index together and what happens when you take out indicators and change the degree of importance given to different dimensions.

And a response from Freedom House

'It is simply not true that Freedom in the World is a blunt, black and white instrument for measuring freedom.

'It is simply not true that Freedom in the World is a blunt, black and white instrument for measuring freedom.

While our index does indeed designate countries as 'Free', 'Partly Free' and 'Not Free', we also publish more granular measurements that are easily accessible to interested readers. For example, each country is given a score on a 1 to 7 scale for its performance on a series of political rights and civil liberties indicators.

We also provide scores for countries on a series of seven category indicators including elections and freedom of expression, which do in fact enable the reader to distinguish between France and Finland - Finland in fact has a slightly better score.'

Arch Puddington, director of research, Freedom House

In-text image: FH findings show that Europe is mostly 'free' democratically (Freedom House, inc)