Dak’art: Diving into the African art scene

Published on

Translation by:

Anam ZafarAn international gathering of contemporary artists is kind of the perfect way to get inside the minds of a new generation. The generation we met wants to build bridges between Europe and Africa by giving the middle finger to stereotypes that often surround the African continent: a region void of opportunity, where Europe is supposedly the only real bastion of accomplishment. Welcome to the Dakar Biennale, a.k.a. Dak'art, a.k.a. the biggest open-air treasure hunt in Africa.

Yes, we know that KANAL (the new Centre Pompidou) has just opened its doors in Brussels, promising to breathe new life into the decaying Belgian cultural landscape. But we want to see something else, to experience something that connects us a bit more to Africa and its artists. For a little over 25 years now, we've been focusing on the Old Continent. It's time to move on.

Avant-garde and the need for action

So we headed to Senegal, the home of Dak’art. Dak’art is the flagship contemporary art event for Africa and its diaspora. For 16 years now, the event has strived to promote the contemporary African creative scene and this year, more than 1,000 artists exhibited their work in more than 308 locations throughout the country’s capital – Dakar – and its surroundings. Like any self-respecting Biennale, Dak’art boasts a pretty avant-garde programme, named ‘OFF’, which allows artists to deploy their work to areas that are not usually destined for art: restaurants, abandoned markets, private homes, public spaces… OFF’s real selling point is its rejection of the sterile white cube formula. This year’s theme is The Red Hour, a reference to a work by one of the founding fathers of the black identity, or négritude, movement in Francophone literature – Aimé Césaire – who writes about transformative energy and the need for action.

We don’t want to waste any time. Programme in hand, we grab a taxi to take us to the building that was formerly the city’s law court, which is one of the five welcome stations for ‘IN’, the Biennale’s core programme. The taxi drops us off right in the middle of the embassy district, where the ocean breeze struggles to compete with the exhaust fumes. The driver vaguely points out a building that resembles a law court, however it turns out to actually be the old customs directorate. The law court has changed location three times in the span of a few years, we are told, and it is hard to distinguish the old from the old (…from the old).

At 1.30 pm, two taxis and five heroic passers-by later, we finally arrive at the real old courthouse. This lavish building, abandoned for 20 years, has been transformed into a museum of contemporary art for the occasion. It’s a fairly intimidating place, and despite its airy freshness, it also possesses the strange feeling of being frozen in time. Simon Njami, the Biennale’s curator, explains to us that it took some time for local citizens to feel comfortable walking by its renovated doors. This former courthouse used to be the site of major trials, such as the one concerning former Prime Minister Mamadou Dia, who had struck a chord with Europe, particularly with people like Sartre and Mitterrand. Some also believe that spirits still reside in the building. In the span of a second, we see one passing by. A pitch-black courtroom with a single light protruding from it catches our eye.

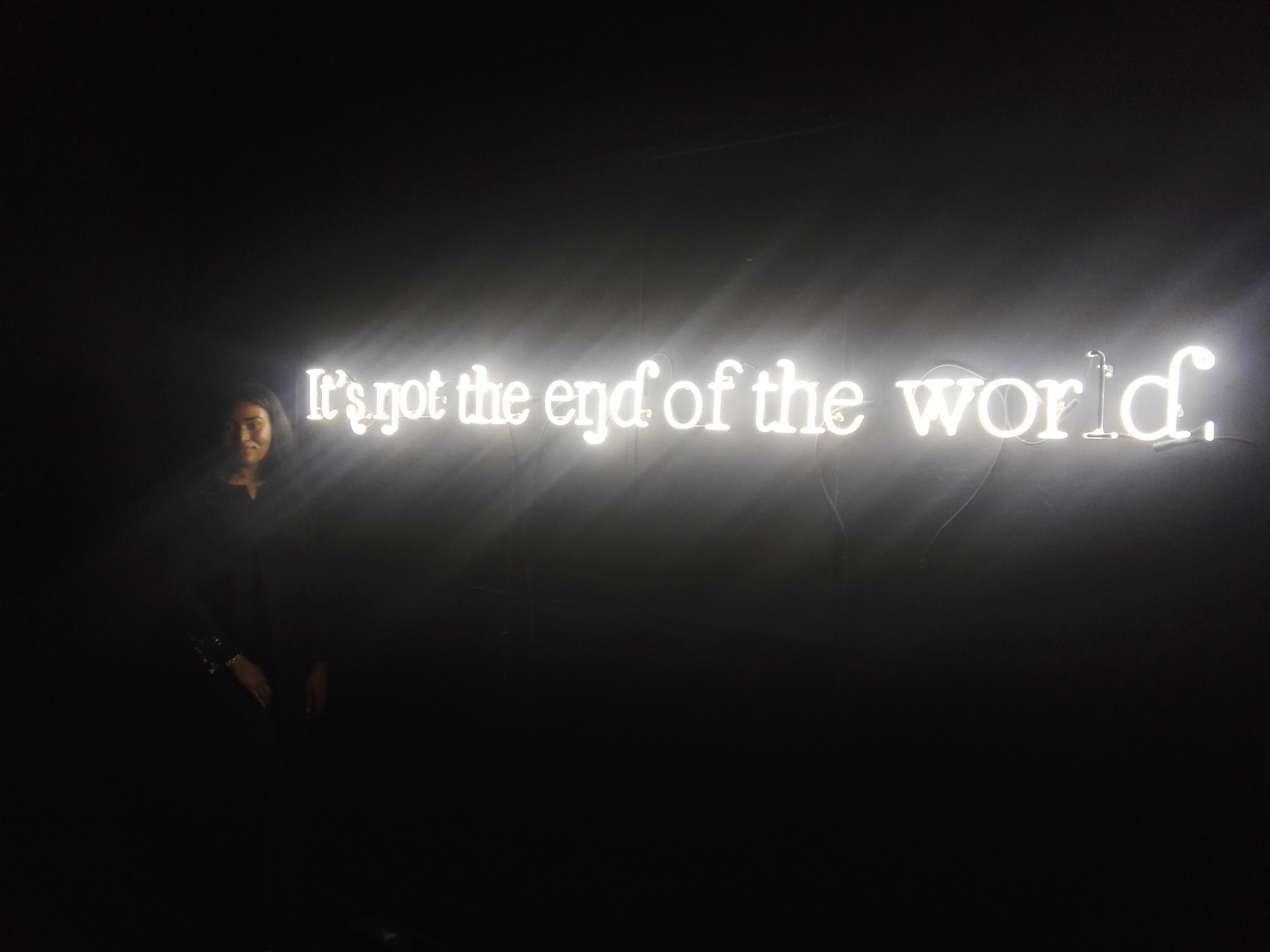

False alarm: it's just a neon sign, which reads "It’s not the end of the wor(l)d", and shines over the work of the Anglo-Zimbabwean artist Dana Whabira. In her work, Dana examines the connection between the formation of language and local identities through the exploration of the British-Zimbabwean colonial relationship. The piece explores how language was seized by colonisers, not as a means of communication but as a means of control and exploitation. Hungry for more information, we immediately search the artist’s name online, which leads us to the hashtag #deconstructingboundaries. "The idea is to defend a culture of hybridity, which would then replace cultural nationalisms," her description reads.

Africa is not a country

In front of Whabira’s piece, a young woman is getting her photo taken. Jessica Colliander, 27, from Sweden, has come to visit her Senegalese family. Visibly touched by the artist’s historical focus, she wishes that African history was more widely taught in European schools. "Coming to the Biennale is like having access to artistic content that you usually can’t find in Europe. These works really have something to say about the continent. It’s a great way to discover Senegalese history, but it's also a window to other African cultures and a chance to discover Africa in all of its diversity, in the most honest way." She’s not wrong. We don’t say it enough, but Africa is not a country. This building is crammed with works by artists from all four corners of the continent and beyond. We continue our travels on the OFF route this time, in search of Core Dump, an exhibition by the South African artist François Knoetze, who sets out to debunk the myth of Silicon Valley’s techno-libertarian utopia. This rush towards technology is not wholly positive for Africa.

The Core Dump exhibition is hosted by Kër Thiossane, a house set within an art garden, within which a whole host of initiatives are nurtured, from Fab Lab to artist residences. Kër Thiossane has been contributing to the continent’s emerging creative economy for 16 years. Its aim? To allow art and culture to facilitate social innovation through the exchange of open knowledge.

We don’t know where to look first. We want to immerse ourselves in these projects and the dynamism of it all and to stay here forever. This is what happened with Marion, a 25-year-old Franco-Ivorian, who came for a 6-month internship at Kër Thiossane and ended up staying. Describing herself as "a Norman through and through", she decided to trade in her Parisian lifestyle to come and learn more about Africa. "Dakar is becoming West Africa’s trendy city. A new generation of artists are coming here, and they are developing their own alternative pan-African scene," she explains, "It may still be in its infancy, but there is a clear desire for Dakar to become the artistic and cultural capital of the whole African continent, and not merely for it to catch up with the international scene or to comply with Western standards."

This new enthusiasm towards the continent springs from a desire to fight against an imaginary Africa that was fabricated in Europe. This image is out of touch with reality, often idealised and sometimes outdated ever since Europeans decided to cut ties with the continent. Nowadays, our Eurocentric culture makes it difficult to sustain a meaningful interest in Africa. Witnessing the effervescent tension surrounding Emmanuel Macron’s arrival in Dakar last February opened Marion’s eyes to many things: firstly, Europe’s deafening silence on its colonial past; next, France’s involvement with the formerly colonised states. Coming to experience life here is perhaps the only way to fuse these two worlds together and to see Africa through different lenses to the ones we usually don when discussing the continent in Europe.

"At least here, we have the opportunity to exist for a reason other than simply being a person of colour."

After an umpteenth heated debate with a taxi driver, we arrive as the night falls at Niaye Thiokers, one of the last shanty towns in the centre of Dakar. We have been told about some areas to avoid, but the atmosphere here is actually rather pleasant, with a sense of youthful authority. We head straight to a 3D printing machine and then to a travelling textile printing workshop, where we meet Marion and one of her assistants who shows us how to programme his 3D printer. "It’s really simple," he tells us, taking out a freshly printed piece. We’d love to believe it, but we would rather try out the textile printer. "All of the fonts are free to download," he continues. Free downloads means free creation... now that's something for the greater good! The festival works like Russian dolls, each initiative hiding another which is just as exciting and inspiring.

A generation fed up with your sh*t

As well as the IN locations, the Biennale is also hosted by the Cheik Anta Diop University, which is exhibiting the work of painter Abdoulaye Diallo, among others. We have to give this one a miss, as on the same day there are violent clashes between the university students and the authorities. The students, who show their discontent by throwing stones, are protesting in the wake of a student’s death a few days earlier, which itself occurred during a demonstration against delayed student grant payments. The scene is almost a mirror of the protests which took place in Senegal in May 1968, triggered for the same reasons. The Senegalese May ’68, as the name suggests, took place at the same time as the May ‘68 movement in France.

Further on, we come across some graffiti: "France dégage," meaning "France get out" in French. The slogan, which reappears in other places throughout the city, is part of a campaign for monetary sovereignty for the African countries that are currently part of the CFA zone (a zone of 14 sub-Saharan countries that all have the CFA franc as their currency). These economic spaces, born out of the evolution of the former French colonial empire, are still under double supervision – French and European – who are still liable to devaluating the currency.

The campaign was launched in 2017 by a student collective named Urgences Panafricanistes which sees the fight against imperialism as a generational struggle: a generation who, for example, worries about large retailers installing big French supermarkets such as Auchan in Senegal’s towns and cities, to the detriment of local entrepreneurs. The collective is a good reminder that some young people didn’t wait for the Biennale and its ‘Red Hour’ to recognise the dire need to counter decades of political and historical oppression. Another example is Yen a marre, a collective of rappers, students and journalists created in 2011, who say that enough is enough: "We must deconstruct and break away from all of the stigmas that are preventing us from really taking off."

Akya Sy decided to do it alone with Idea Box. This young designer was inspired by the country’s creative potential, and decided to create a guesthouse in her hometown of Dakar for African artists. Inside this oasis of peace, we speak to Sorana, a Belgian-Beninese graphic artist who finds that people generally still find it hard to imagine that an African capital city can be as full of opportunity as London or New York, and maybe even more so. "Yeah, there are electricity and water shortages but after a while you stop worrying about it," she claims. "At least here, we have the opportunity to exist for a reason other than simply being a person of colour. Even if, at the end of the day, we are still considered Europeans, and are confronted with our own preconceptions about Africa."

As luck would have it, we come across the famous painter Abdoulaye Diallo during our last outing, whose works we tried to see two days earlier. Despite being 65 years old and having started his painting career at the age of 59, he considers himself as one of Senegal’s ‘young’ engaged painters. Sipping on mint cordial, he talks us through his 2-metre-high painting and about art’s role as a means of emancipation for young people of the continent and beyond. "What makes me the happiest is when students or young artists ask if they can borrow the content of my work, to feed their minds in order to give more content to their freedom."

We end by asking him for his thoughts on the Biennale. He replies that what he likes most of all is "the sense of fun and nonsense, like being part of a game." We have enjoyed ourselves too, we tell him. The epic art saga that is Dak’art has opened our eyes almost unintentionally to the "multiple possibilities that are available to us on the continent, should we decide to embrace them completely."

Translated from Dak'art : plongée dans la movida africaine