Daesh: Enemy of today and tomorrow

Published on

Translation by:

Kath Burns

Kath Burns

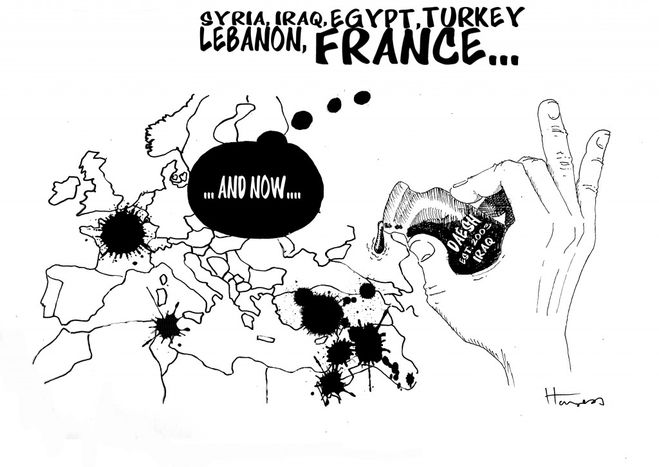

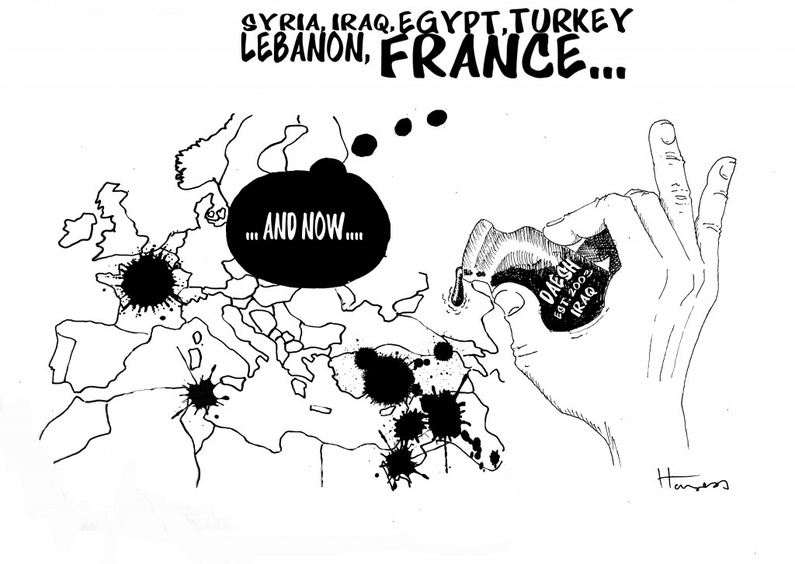

Suicide bombers blew themselves up in Paris for the first time on 13th November. A few days before, Lebanon experienced its worst attack since 1990, with two suicide bombers targeting Beirut. On 2nd December, a mass shooting at a social centre in San Bernardino, California left 14 dead and 22 injured. How can we decipher a conflict that's gradually being exported?

Syria: the origins of the conflict

In 2011, the world looked on as the Arab people rebelled in what would later be called the "Arab spring". One by one, the people of the Maghreb and the Middle East rose up and toppled their leaders. Countries like Tunisia and Egypt saw their dictatorial regimes tumble like houses of cards, following popular uprisings.

The Arab spring began to reach Syria by February 2011. Bashar al-Assad intended to appease the movement through various social reforms, but that wasn't enough for the Syrian people, who wanted to bring down their leader.

The Syrian crisis really began in March 2011, through massive demonstrations in the country's larger cities – notably in Daraa, where the first clashes took place between the Syrian people and the national security forces – who used real bullets – leaving more than 100 people dead. That marked the beginning of a civil war that would set Syria alight.

Against that backdrop, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who succeeded Abu Musab al-Zarqawi as leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq, took advantage of the widespread chaos and decided to intervene in the Syrian conflict by sending around 100 of his men to fight alongside the rebels opposing Assad. Thus Al-Qaeda in Iraq merged with the al-Nusra Front – the other branch of al-Qaeda in Syria – to form what we now call the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).

A change in Daesh's strategy

Al-Baghdadi made his first public appearance on the 5th of June 2014 in a mosque in Mosul, a city that had recently been won by ISIL. In his speech, he stated his intention to establish a caliphate of which he would be the caliph: "I have been entrusted with a great mission. I have been tested and designated as your guardian. Obey me as you obey Allah."

However, the recent attacks in Lebanon, France and the US suggest that Daesh's plans have widened. While they had previously concentrated on creating a caliphate and fighting their enemies in Iraq and Syria, they're now adding strings to their bow by becoming more international, as al-Qaeda did in the bin Laden era.

However, the recent attacks in Lebanon, France and the US suggest that Daesh's plans have widened. While they had previously concentrated on creating a caliphate and fighting their enemies in Iraq and Syria, they're now adding strings to their bow by becoming more international, as al-Qaeda did in the bin Laden era.

What are the reasons behind the change? It could be a reaction to strikes against ISIL by the western coalition and an attempt to encourage western political leaders to end the strikes. Alternatively, it could be a way of encouraging military intervention on the ground, in order to defeat their armies there.

There's also a theory that Daesh is having difficulty recruiting new jihadists – notably due to Turkey's decision to close its border with Syria, following the attacks in Suruç and Ankara. ISIL might therefore be forced to encourage willing jihadists to remain in their respective countries and plan attacks from there, rather than take the risk of travelling to Syria.

Daesh versus the world?

It's important to note that ISIL, as an organisation, is much more nebulous and harder to define than al-Qaeda. Al-Qaeda, formerly led by bin Laden, had a pyramid structure, with orders coming from its most senior leaders. With Daesh, however, we're looking at an organisation that gives its jihadists a certain level of freedom, which would explain why certain acts of terrorism are committed by Daesh jihadists without necessarily being claimed by the main organisation.

It's therefore more than likely that the attacks in Paris on 13th November were led by a small French group who had sworn allegiance to Daesh, without having been ordered to carry them out by senior figures in the terrorist group. We can effectively consider the Paris attacks a strategic error on ISIL's part, since the people killed were of all faiths, including Islam.

As a result, it's not possible to garner support among a non-radicalised fringe of the population who feel rejected by western society, because people of their own religion were also targeted. This wasn't the case in the Charlie Hebdo attacks that targeted people who, according to Daesh, were Islamophobic.

It would appear that ISIL has succeeded in uniting countries against it that would normally consider themselves enemies – but behind those countries' common goals lie two blocs of allies with differing and sometimes opposing interests. The difference between them hinges on the split between Shia and Sunni Muslims in Iraq and Syria.

On one side, we have the Shia bloc, comprising Bashar al-Assad's army and Hezbollah in Lebanon and Iran. Its goal is to keep Assad in power, since he can guarantee a Shia axis running from Iran to south Beirut, via Damascus.

The Shia axis counts another weighty partner in the form of Russia, Assad' s main ally. Moscow's aim is clear: keep the Syrian port of Tartus – his only gateway into the Mediterranean – within Assad's sphere of influence. Finally, there's Iraq, one of the biggest Shia countries in the region. It's supported by Iran and funded by France and the US, who are fighting Daesh for the sake of their internal security.

On the other hand, we have the Sunni bloc, comprised of the Free Syrian Army, several radical Sunni groups such as the al-Nusra Front, and Kurdish guerrilla fighters in Iraq and Syria (the PKK and YPG). Their short-term aim is a shared one: overthrow Assad.

On the other hand, we have the Sunni bloc, comprised of the Free Syrian Army, several radical Sunni groups such as the al-Nusra Front, and Kurdish guerrilla fighters in Iraq and Syria (the PKK and YPG). Their short-term aim is a shared one: overthrow Assad.

This grouping, which is more a tactical than ideological one, runs a strong risk of splintering if Daesh falls – particularly since the axis is being funded by three directly competing countries: Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey. Their objective is to expand their respective influence by opposing – with all possible means – the ambitions of Iran, even if that means fighting with greater conviction against Assad's regime than Islamic State's.

One key question remains unanswered: what will become of these alliances once Daesh is eliminated? Is the groundwork being laid for an even bigger war than the one against ISIL?

---

This article was published by our local team at cafébabel Brussels.

Translated from Daech, ennemi d'aujourd'hui et de demain