Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia: domino game of governmental crash

Published on

Translation by:

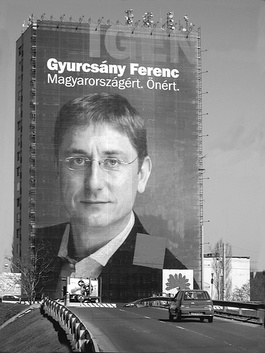

Astrid vWOn 22 March, Hungary’s socialist prime minister, businessman Ferenc Gyurcsany, announced his resignation for 14 April. There is a huge amount of strategy beneath his move and it reveals a trend appearing in central and eastern Europe. Today, the Czech Republic establishes a new chapter

Ferenc Gyurcsany’s second government was stillborn. Shortly after he was inaugurated in 2006, some recorded conversations filtered through to the press and the population in which he acknowledged that to win the elections, he had had to hide the reality of the difficulties that Hungary faced. This had him worried. The Hungarian businessman has led a socialist government in coalition with the liberals from the democratic forum, knowing that Hungary needed liberal reforms, but without convincing the employers and trade unions.

Ferenc Gyurcsany’s second government was stillborn. Shortly after he was inaugurated in 2006, some recorded conversations filtered through to the press and the population in which he acknowledged that to win the elections, he had had to hide the reality of the difficulties that Hungary faced. This had him worried. The Hungarian businessman has led a socialist government in coalition with the liberals from the democratic forum, knowing that Hungary needed liberal reforms, but without convincing the employers and trade unions.

Whether they were Hungarian or foreigners, all the analysts that were consulted agreed that the country’s biggest problems was its political polarisation: it renders futile any attempt by the government to reach any kind of agreement with the leading opposition party, the conservative Fidesz, 'who has systematically opposed all the socialist’s proposals, despite knowing full well they were indispensable,' explains Gergely Romiscs, a researcher from the Hungarian institute of international relations. However, Andras Vertes, director of the Hungarian think tank, GKI economic research, describes the true Hungarian problem differently: 'The country doesn’t have public debt above the European average, nor a high unemployment rate or high level of inflation. The problem is that the country depends on a 70% private foreign investment, and, thanks to the crisis, this has disappeared, leaving the Hungarian economy without funds and suddenly paralysed.'

Everything points toward the fact that, in proposing liberal Lajos Bokros – an ex-colleague and former finance minister from the governmental coalition – as the candidate to be the new prime minister, Gyurcsany hopes to defuse the explosive discussions and opposition against him, generated by Fidesz, who, between 1998 and 2002, didn’t manage to introduce any liberalising reforms in Hungary either.

The threat of political tsunami

The eastern countries do not form a homogenous bloc, as demonstrated three weeks ago by Hungary being left in the lurch in its EU petition for a 160 euro billion plan to tackle the crisis in those countries. This is a typical scene, which highlights past mistakes and foresees new governmental crises in the east. The most obvious cases are those of the Czech Republic and the Ukraine.

The eastern countries do not form a homogenous bloc, as demonstrated three weeks ago by Hungary being left in the lurch in its EU petition for a 160 euro billion plan to tackle the crisis in those countries. This is a typical scene, which highlights past mistakes and foresees new governmental crises in the east. The most obvious cases are those of the Czech Republic and the Ukraine.

In the latter the crisis has caused a severe drop in the price of iron and steel (accounting for almost half of its exports). Soon to be discovered are the reformative shortcomings of the liberal coalition between president Viktor Yushenko and prime minister Yulia Timoshenko. The risk in this country is the appearance of extremist forces that will in turn fuel the temptation to build the new state using authoritative solutions, as has already happened in Belarus.

On the other hand, the Czech government’s nationalist ammunition has run out and they can no longer hide their inadequacy with regard to solutions to the crisis. Ony 24 March they will be put to a vote of censure that could end in elections in the middle of their EU presidency. Their ultraconservative partners do not agree with their ratification of the Lisbon treaty in the lower house, and their only alternative, however surreal it may appear to liberals such as those from the ODS, is to come to make a pact with the communists.

On the other hand, the Czech government’s nationalist ammunition has run out and they can no longer hide their inadequacy with regard to solutions to the crisis. Ony 24 March they will be put to a vote of censure that could end in elections in the middle of their EU presidency. Their ultraconservative partners do not agree with their ratification of the Lisbon treaty in the lower house, and their only alternative, however surreal it may appear to liberals such as those from the ODS, is to come to make a pact with the communists.

Translated from Hungría inaugura el dominó de las crisis de gobierno en el Este