Copenhagen: Islam, identity and integration

Published on

Translation by:

Elizabeth Arif-FearMore than 10 years after the controversial publication of images of the Prophet Mohammed, and a year after attacks on cartoonist Lars Vilks and a synagogue shook Copenhagen, Danish attitudes to the city’s 300,000 strong Muslim community have changed. We visit youth associations and cultural centres to discuss integration and the fight against radicalisation in a climate of Islamophobia.

"When the cartoons of Mohammed were published, we noticed a change in the way the Muslim community was viewed by the media and political classes. We’re living in a less tolerant climate due to terrorism, and for some people this climate has become hostile. Some people believe that we’ve even gone backwards by 10 or 20 years in terms of integration." These are the words of Waseem Rana, one of the directors of Munida – a Muslim youth organisation that promotes the integration of Muslim identity in day-to-day Danish society.

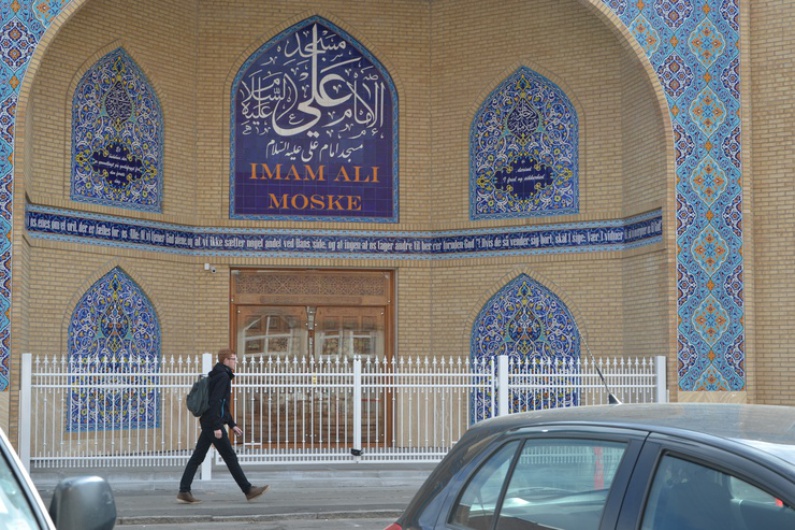

We went to Nørrebro, north of Copenhagen, to explore the old workers' district. Here, industrial architecture stands side by side with evidence of multiculturalism and gentrification: Middle Eastern shops, modern pubs, skate parks, street art and small design workshops. It’s no coincidence that here you can also find prayer halls and Muslim cultural centres.

Inside Wakf Mosque

Everything’s ready for evening prayers. Waseem is waiting along with other young men at the entrance to Wakf Mosque at the Islamic Society in Denmark. The prayer hall is built inside two large warehouses and hosts around 100 worshippers of all ages. "Munida was set up in the early 2000s by Ahmad Abu Laban," Waseem (38) tells me. Waseem was born and raised in Copenhagen by his Pakistani parents.

Later disappearing in 2007, Laban was a central figure in the controversy surrounding the publication of cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed in 2005 by the Danish daily newspaper Jyllands-Posten. He not only took part in the Middle Eastern delegations, but was also partly responsible for the "Akkari-Laban dossier" alongside Ahmed Akkari, which denounced the climate of Islamophobia within Danish society and was accompanied by a rise in protests and violence in the area.

"Laban wanted a youth section, so a group of 4 or 5 young people was formed on the side. Today there are 500 of us – 60% of which are women. We’ve members from around 40 nationalities and our activities cover all social aspects relevant to Danish youth."

This includes not only social and recreational activities but also educational initiatives. "We’re trying to help young Muslims to develop their identity within Danish society. If they have firm faith and are confident about their identity, they’ll become better citizens," he adds.

Prayers start and we receive a warm welcome with only a few wary glances. "Unfortunately, for the last three weeks we’ve been living in a climate of suspicion due to a story on a Danish hidden camera show," Waseem explains. This was an interview on the public channel TV2 with an imam from Grimhøj mosque in Aarhus – an imam in support of stoning women for adultery and the right to kill apostates.

Prayers start and we receive a warm welcome with only a few wary glances. "Unfortunately, for the last three weeks we’ve been living in a climate of suspicion due to a story on a Danish hidden camera show," Waseem explains. This was an interview on the public channel TV2 with an imam from Grimhøj mosque in Aarhus – an imam in support of stoning women for adultery and the right to kill apostates.

"They chose a radical episode that risks destroying all the progress that's been made over the years towards integration," explains Waseem. "After the attacks in Paris and Brussels, my mother and sister were stopped in the supermarket by a man who accused them of being responsible… He was drunk – no doubt about it – but it's still a sign."

Reaching out to young radicals before hate preachers do

We stop in the library, which every year hosts thousands of visitors from schools and universities who come to learn about Islam. The person in charge here is Nils, a 24-year-old physics student who converted to Islam when he was 17. "I’m responsible for looking after new converts to Islam. We get together every Monday and we talk about the fundamental basics of the religion," he explains.

Born and raised in a Christian family, he converted in 2009. "My parents told me that God exists and I believed in it, but then as you get older, you reach a certain age and you start to ask yourself questions. I met some young Muslims at high school and so I discovered the Qur’an and the Prophet Mohammed and after three months I converted." His family were accepting of his decision, but not without a few jokes: "My mother used to make jokes and ask me when I was going to blow myself up."

According to a study by The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, since 2011 an estimated 125 foreign jihadi fighters have left Denmark – at least 62 of which have since returned home. In addition, Omar El Hussein, one of the perpetrators of the 15th of February shootings in Copenhagen in 2015, was born and raised in Denmark within a family of Jordanian-Palestinian origin. He was just 22 years old at the time.

According to a study by The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, since 2011 an estimated 125 foreign jihadi fighters have left Denmark – at least 62 of which have since returned home. In addition, Omar El Hussein, one of the perpetrators of the 15th of February shootings in Copenhagen in 2015, was born and raised in Denmark within a family of Jordanian-Palestinian origin. He was just 22 years old at the time.

"If it weren’t for conflicts in the Middle East, hate preachers would have less of a hold and an impact on young people. Many young jihadis go to Syria convinced that they’re going to fight injustice," says Waseem. "But fighting injustice doesn’t mean going to fight in Syria. This will destroy them, their cause and the image of Islam. They have to transform negative impulses into positive energy; learning, writing, venting their frustrations. If we don’t speak to them ourselves, extremist preachers could do so instead, and could control them."

"Our generation is trying to define Islam within a Danish context"

Right from the very start, such efforts have also included Minahj-ul-Quran International (Denmark) – an NGO founded in 1981 in Pakistan by Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri that promotes tolerance and interfaith dialogue. Hassan Bostan – a 25-year-old lawyer – welcomes us at their centre.

"90% of our members are originally Pakistani, arriving here in the 70s and 80s," explains Hassan. "We young members who were born and raised here are trying to define Islam within a Danish context as a universal religion that can be practiced in any country and at any time in history – assuming that you can define its role and understand how young Muslims can integrate. For our parents who had just arrived in Denmark it was difficult. We want to move forwards."

We visit the rest of the building. Heading upstairs we find the prayer rooms, followed by washrooms for performing ablutions and several rooms where children attend classes. Along our way we meet many children. They’re all directed towards the large prayer hall where the imam teaches them how to recite the Qur’an.

"We teach classical Islamic science, meditation and Sufism to free the heart from hatred and negative thoughts and ideas," Hassan says, an ex-member of the Danish Ethnic Youth Council. But that’s not all: "We work with Jewish and Christian associations and we’ve also taken part as a steering group in a programme set up by the city of Copenhagen aimed at understanding radicalisation and providing political solutions."

"We teach classical Islamic science, meditation and Sufism to free the heart from hatred and negative thoughts and ideas," Hassan says, an ex-member of the Danish Ethnic Youth Council. But that’s not all: "We work with Jewish and Christian associations and we’ve also taken part as a steering group in a programme set up by the city of Copenhagen aimed at understanding radicalisation and providing political solutions."

This is something also carried out on a European level with the assistance of RAN (Radicalisation Awareness Network) – a community based programme aimed at preventing radicalisation – and additionally through seminars studying counter-terrorist material including: Fatwa on Terrorism and Suicide Bombings (Tahir-ul-Qadri) and the Islamic Curriculum on Peace and Counter-Terrorism (Minahj-ul-Quran International, Tahir-ul-Qadri).

The Women’s Mosque

Then there's the question of women: "Women’s participation is a Pakistani cultural problem outside of the religion itself," says Hassan. "We have a Women’s League and in all activities – from sporting to recreational activities – men and women are on the same floor of the building." This is a topic that led to an innovative cultural experiment aimed at integration: a women’s mosque. Known as Mariam, it’s a home for all Muslims, but Friday prayers are only led by fem-imams – female imams.

The first female imam was the founder Sherin Khankan, 41 years old, born to a Syrian father and Finnish mother, a columnist and commentator known in Denmark for her publications on Islam and her radical left wing activism. "The debate’s been moving forward since 2011 when we founded the Critical Muslims forum. We wanted to overturn Islam’s patriarchal structure," Khankan explains. "The Qur’an does not forbid women imams."

The mosque, which is currently under construction, is based in an apartment in the heart of Copenhagen – mere metres from a street full of tourist souvenir shops. On the 9th of February, as announced by the AFP new agency, the first Islamic marriages and divorces took place here. This was the first step on an ambitious road that is very much focused on educating young people. "We’re centred on tradition but we put this into context in the 21st century," explains Khankan. "The new generations don’t know their own origins. We want to introduce them to Islamic philosophy and thinkers such as Ibn Arabi who approved of female imams."

The message has already won over its first group of young Muslims. "They came to a meeting at university and joined our project," Khakan concludes. "We can act as a point of reference for the new generation."

---

This feature report is a part of our EUtoo 'on the ground' project in Copenhagen, seeking to give a voice to disenchanted youth. It is funded by the European Commission.

Translated from Copenaghen: una storia di Islam, identità e integrazione