Conversation with Leo Tolstoy on centenary of his death

Published on

Translation by:

Cafebabel ENG (NS)20 November 2010; the Russian writer famed for his masterpieces War and Peace and Anna Karenina is about to die for the hundredth time. We meet him before he takes his last train

We’re meeting at the station in Tula, which is 165 km south of Moscow. Dawn is breaking. I wait for a certain Count Lyev Nikolayevich Tolstoy. The autumn cold is as relentless as the tips of a rake that will tear at your sides. For a moment, I think it’s a crazy idea. I decide to give up and leave. Then I hear a deep, breathless voice: ‘run away! We must run away.’ It's him.

Those were Leo Tolstoy's famous last words after all, uttered on 20 November 1910. Repeating the ritual of death is a cruel fate dealt to all modern immortals. And he is one of them.

Leo, women and society

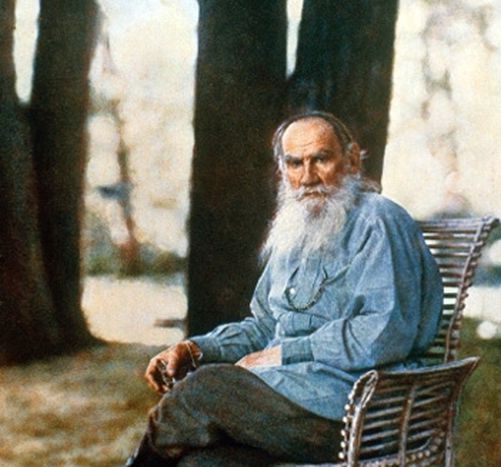

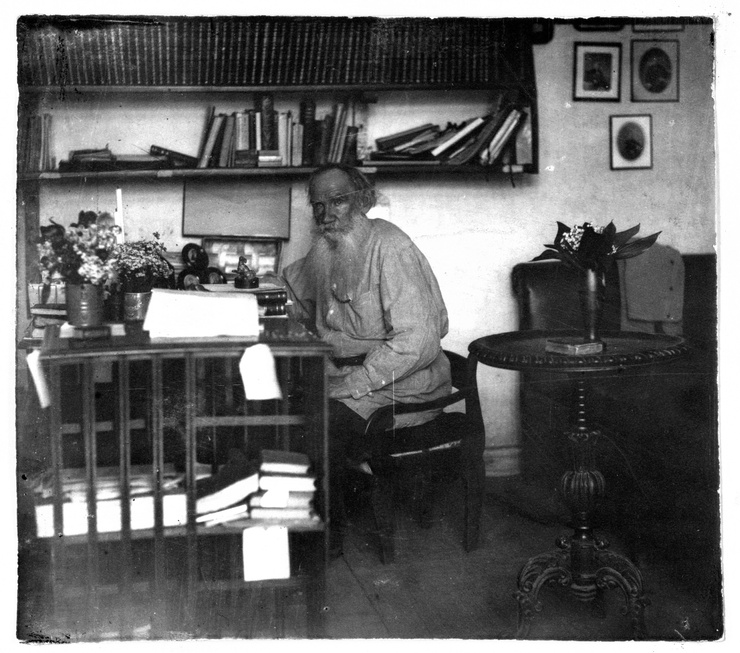

Wrapped in a heavy wool cloak, the lines on Tolstoy's face sink into his long, white beard. He looks a tired man, weak and emaciated from his pneumonia, though his eyes are full of hope. He looks disappointed, having expected the train to Crimea to already be here. Luckily for me it is not. ‘Why the rush?’ I ask, intimidated. ‘It's my wife Sofia,' he says, anguished. 'But what do you know, you're young, unmarried. They only think about money. They are all obsessed, she ... all my children! I have no doubt that she would be ready to kill me for my will ... run away! We must run away.'

I thought the 82-year-old had a good relationship with the fairer sex. ‘You know who the protagonist of the Kreutzer Sonata is?’ he pants, referring to his 1889 novella. ‘Yes - Pozdnyshev is Vasya, the man who brutally murders his wife in the grip of jealousy,’ I reply. ‘Want to know more?’ he offers. ‘I am Vasya. I am my wife’s murderer. Well, let's say I wanted to be. You do not know how many times I wanted to do it. Women are only interested in money.’ I am confused. I think of the thirteen children he has had with his wife, five of whom died naturally. Did he also see his wife, Sophia Bers, whilst writing Anna Karenina, whose life Tolstoy ended in suicide? ‘Yes, but in this novel she is not the problem, it’s everyone else around her. They are the real murderers. Society, our hypocritical and materialistic society, killed Anna Karenina! As you see young man, no-one is innocent.’

I thought the 82-year-old had a good relationship with the fairer sex. ‘You know who the protagonist of the Kreutzer Sonata is?’ he pants, referring to his 1889 novella. ‘Yes - Pozdnyshev is Vasya, the man who brutally murders his wife in the grip of jealousy,’ I reply. ‘Want to know more?’ he offers. ‘I am Vasya. I am my wife’s murderer. Well, let's say I wanted to be. You do not know how many times I wanted to do it. Women are only interested in money.’ I am confused. I think of the thirteen children he has had with his wife, five of whom died naturally. Did he also see his wife, Sophia Bers, whilst writing Anna Karenina, whose life Tolstoy ended in suicide? ‘Yes, but in this novel she is not the problem, it’s everyone else around her. They are the real murderers. Society, our hypocritical and materialistic society, killed Anna Karenina! As you see young man, no-one is innocent.’

Leo’s cynical and opportunist universe reminds me so much of today. It’s like the one that surrounds Ivan Ilyvich’s poor body in the eponymous 1886 novella. His character dies after a simple blow to his side whilst putting up curtains. He is not believed throughout his ensuing illness which causes him to die a second death. He is devoured by society, the materialist hypocritical hyenas around him who don’t know how to deal with his mystery illness. They seem to have waited for nothing more than his death. ‘What a bleak picture,’ Tolstoy concludes.

War, peace and the bourgeoisie

'But Ivan Ilyvich saw the light and died exclaiming ‘what a joy!’’ continues Tolstoy, apparently reading my mind. ‘It will be the same for me too soon. You do not know what a relief that is. I have seen hell with my own eyes several times. When I was twenty I only cared about parties and the game. Then I was saved by two people: my fellow Russian writer Ivan Turgenev, who got me out of my gambling habit by lending me money, and the western writer Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who showed me the right path through his works.’ And then of course there was the war, I say. ‘It was when I was hovering between life and death at the siege of Sebastopol that I decided I wanted rid of my vices. I began to dream of a better society and the right to pursue life’s purity as nature wished it. I eventually also became a vegetarian. I could not bear more suffering, let alone that of animals. I left everything behind. I don’t care about luxury or objects around me.’ So Tolstoy was a sort of environmentalist before his time. ‘I do not know what you mean,’ he replies, looking at me. ‘One thing is for sure. My wife doesn’t like ‘environmentalists’. It all started to go wrong between us when I rejected these things. She clearly likes meat too much.’ Sofia sounds rather like the protagonists of his novels, who are always at the ready, sinking their fangs into succulent portions.

‘So you went from meat to the host,’ I venture on. ‘Think of it as you wish,’ Tolstoy replies. ‘The orthodox church did not appreciate my ideas. I was excommunicated in 1901. I was threatened with being locked up in a monastery. Luckily I was already quite famous. Sometimes that helps.’ So, what was revolutionary in your thinking, I ask, conscious our time might be running to an end; Tolstoy was inspired by a variety of spiritual ways of thinking. ‘I do not know,’ he shrugs. ‘Maybe those were just my thoughts and nothing more. I didn't only read the bible, but I read buddhist and taoist texts too, and the philosophers on top of that. Those obviously weren’t popular choices for the orthodox christians.'

Time has escaped us; the train is here. Leo climbs onto a third-class carriage without a single piece of baggage. Dr. Makovetsky accompanies him. But Tolstoy won’t be needing his trusted physician and friend. I already know that his journey will be prematurely stopped at Astapovo station, where a mass of people will surround him as he falls to die at the remote railway stop. Bon voyage, master, I say, as the train whips him off to his hundreth death. Or perhaps towards his actual life.

Translated from Intervista a Lev Tolstoj: cento volte morto per cambiare il mondo