Communism perspectives: 'discontinuous history of art in eastern Europe'

Published on

Translation by:

Oliver

Oliver

3 October marked twenty years after the fall of the communist regime. One exhibition in Paris this summer asked the central question: is there any value in the question of 'east-west’ opposition today?

The title of the Promises from the past: a broken history in former Eastern Europe exhibition, which ran until 19 July at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, is taken from a quote by Walter Benjamin (On the Concept of History, 1940). It evokes the present and our capacity to construct it while neither renouncing the past nor elevating it. The exhibition sets the work of communist-era eastern European artists and that of their contemporary descendants in opposition. Zig-zagging through the gallery, it takes the form of a guided tour.

Polish curator Monika Sosnowska

'To elevate the past' is the proposition of Monika Sosnowska's curation. The 38-year-old Polish artist leads us through an immense zig-zag of white panels. Little by little, photographs, drawings, maquettes and videos are unveiled on them. They're all more or less recent, but without any logical chronology. Monika Sosnowska's intention is to confront the works of young artists with the works of their elders around a common theme. Two fundamental questions are spelled out on canvas: how to overcome the concept of linearity in history; how to think about the opposition of east and west in Europe today? In response, the zig-zag leads us through seven themes: ‘Beyond modernist utopias’, ‘fantasies of totality’, ‘anti-art’; public space/ private space’, ‘feminine-feminist’, ‘micropolitical gestures and critiques of institutions’ and ‘utopia revisited’.

Together these sections of varying lengths illustrate Monika Sosnowska’s idea of revisiting eastern Europe's past through its present. While her zigzag route symbolises the discontinuity of history, her curation picks up on the modernist architectural canon of communism; an urban utopia whose promises – and failures – are now known to us. The Ryki-born artist proposes reexamining these architectural canons, which have been central to both the doing and the undoing of the towns and cities of eastern Europe, ‘in a post minimal and conceptual vein’.

Ambitions of past: results?

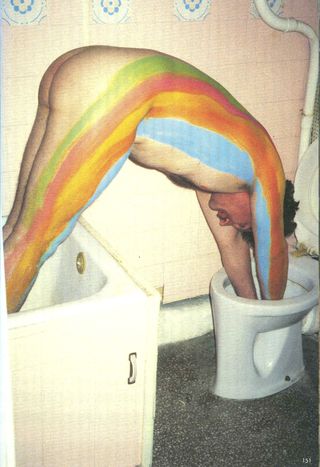

Arriving at ‘Beyond modernist utopias’, we come face to face with the body of Polish artist Cezary Bodzianowski, painted in the colours of the rainbow, with his head plunged into a toilet bowl (Rainbow Bathroom, 1995). Then we encounter Dammi i colori ('Give Me Colour'), a 2003 work by the Albanian video artist Anri Sala. In this film from the same year the artist Edi Rama, also the socialist mayor of Tirana (Albania), gives a commentary (without any evident self-indulgence) on the plans that he had dreamed up years previously for his town. Travelling one of the roads where the vibrant colours of the buildings stand alongside the rutted pavements covered in rubbish, Edi Rama recalls his vocation, both as mayor and as an artist: ‘The question is to find a way to render this town habitable.’ Then he adds, regretfully, ‘I think that the ambition to make this town a town of choice is in itself a utopian dream.’ In following the example of Edi Rama, the exhibition invites us to consider the ageing ambitions of the past.

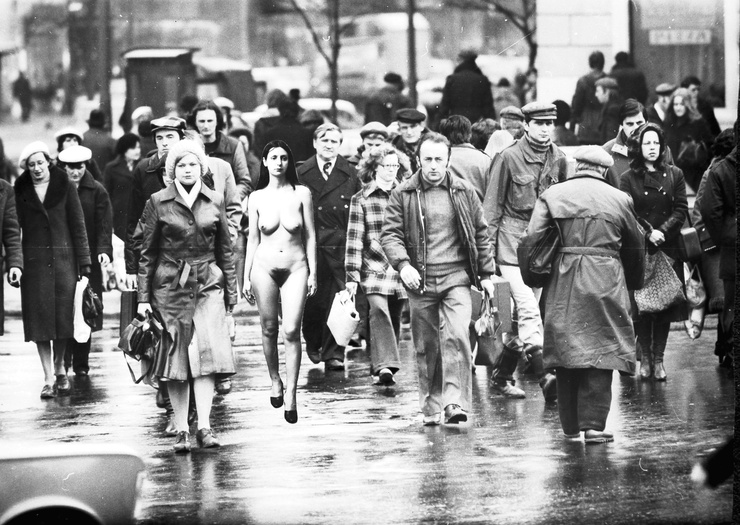

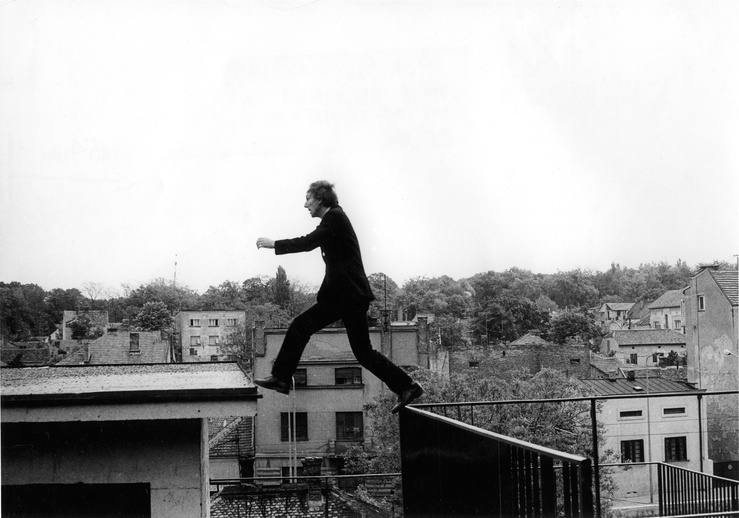

In following this guided tour, we see that the themes complement each other. In the section entitled ‘Fantasies of totality’, the weight of the collective on the individual is questioned with derision in Kardynal ('Cardinal', 2001), the video of Polish sculptor Pawel Althamer being baptised in mud, or on the fringes of madness with the Romanian artist Ion Grigorescu. His film Boxing, filmed in secret in 1977, consists of superimposed negatives showing the naked artist having a boxing match with himself. It illustrates the ‘schizophrenia of life in communist Romania’. By turns moving and disturbing, the works in the exhibition are always anti-authoritarian. In the section ‘Public space / private space’, the protest becomes more overtly political. The micro-actions of Czech artist Jiri Kovanda in public places are a testimony to the climate of censorship and suppression of the individual in Prague in the 1970s. To go against the crowd, to abandon caution – and to immortalise it on camera – is to transform a primary and fundamental liberty into a political protest. The poster for the exhibition is an image from the making of the film N.P. 1977 by the Serbian Nesa Pariovic. In it we see the Belgrade-born artist following a predetermined straight line across his hometown on foot, staying the course regardless of the obstacles he encounters.

Heritage to cultivate

The notions of ‘Public/ Private’ were very different amongst those who lived on either side of the iron curtain. Here we touch on the central point of the exhibition: is there any value in the question of 'east-west’ opposition today, twenty years after the fall of the communist regimes? Has the march of time wiped away their differences? The works of the younger artists presented at the Pompidou Centre are not so optimistic. The Israeli artist Yaël Bartana picks up on the tropes of zionist ideology in her film Mur i Wieza ('Wall and Tower', 2009). A common ideal, a source of hope for jews mistreated by history, this imaginary return to Warsaw evokes the terror of the great political ceremonies which we now know well from official images and films.

Past and present meet continuously in this dialogue between the figures of art in communist Europe in the 1970s, and their contemporary successors. Without cultivating nostalgia, the exhibition shows that it’s neither possible, nor desirable, to wipe the slate clean of the past. To live today in Prague, in Tirana or Budapest, is inevitably to contemplate the vestiges of a past made with promises by a regime which held on, above all, to the construction of grand utopias.

Images: exhibition poster from the Centre Pompidou: ©Goranka Matic, courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Contemporary Art Belgrade; Rainbow, Bathroom, Lodz, 1995 ©Monika Chojnicka; Self-identification: ©Ewa Partum

Translated from L'art en Europe de l'est ? Toute une Histoire...