Claudio Stassi and Giovanni Di Gregorio 'didn't want to show people being killed in Brancaccio'

Published on

Translation by:

Rosh Mahtani

Rosh Mahtani

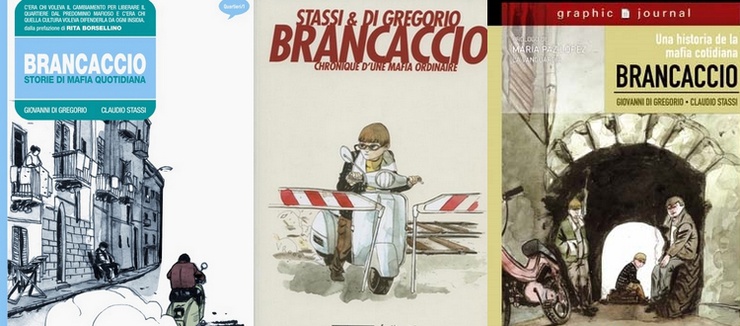

The 2006 comic book has been already been translated into French and Spanish. Both the author and scriptwriter are based in Barcelona, having escaped Sicily because 'the mafia culture is gaining strength'

We have to walk half way across the historical centre of Barcelona to find a peaceful place to talk. Finally, we head for the cordial atmosphere of the ‘serene’ Romesco restaurant, with its traditional dishes coupled with the odour of oil and smoke. On their return from the Angoulême international comics festival, which took place between 29 January and 1 February, I find myself speaking to the two authors of Brancaccio. The Italian comic book was published in 2006 and was subsequently translated into French and Spanish.

Brancaccio/ Gomorrah?

Claudio Stassi, 31, and Giovanni Di Gregorio, 34, depict the intertwining stories of daily life in Brancaccio, a district of Palermo, where Father Giuseppe Puglisi was parish priest of San Gaetano; the outspoken critic of the mafia was killed in 2003. In the book, the child character of Nino is the anchoring thread. The entire story is set in a mafia-permeated atmosphere - not one of gangsters and bombs, but rather one that is more persistent, permanent and quotidian. ‘Actually, Brancaccio was written by four hands - only a Sicilian illustrator could possibly render these brief dialogues in which even one glare is enough,' explains Giovanni.

Brancaccio is also the district where Claudio lived for three decades. ‘Creating this comic is our way of expressing everything we think about our area,' he says. 'It was a way in which we could vent the many things we were carrying inside of us.’ The everyday aspect of the stories in Brancaccio resembles the way that events are narrated by the characters in the 2008 film (not book), Gomorrah. ‘There is definitely the desire to speak about the everyday, like in the film,' Giovanni elaborates, ‘but Gomorrah is definitely more violent. Our intention was not to display gore through blood and guns. We didn’t want to exhibit people being killed.’

In Sicily, publishing every act of life is practically impossible

Thanks also to the fact that there have not been a great deal of homicide cases in Sicily since 1993, one realises that everything is set aside under an iron clad politics-mafia pact. A mafioso no longer supports one politician per se, but enters directly into politics itself, before politics becomes the mafia. ‘Why has (the Sicilian fugitive Bernardo) Provenzano casually been taken (he was captured in 2006 - ed) whilst the new government is being elected?’ both ask. What impact does the mafia have on daily life, how can it be highlighted? Claudio explains that ‘for every little thing you must have a saint in paradise. In other words, every act of civil life is impossible - even down to making a hospital appointment. It is said that the attitude of the mafioso is prevailing, because it is a necessary part of living. It is even said that the mafia come out of it stronger, as the mafia culture is strengthening itself.’

‘In Palermo, 80% of shops pay protection money (il pizzo),’ adds Giovanni. ‘Everytime you go shopping, technically, you are reinforcing the mafia…’ And what about the initiative like that by Italy’s leading industrial union Confindistria, who tried to encourage everyone to stop paying? ‘It's a great initiative, but how can you distinguish between those who have paid and those who haven’t?’ Well, in these times of creative accounting...

Comics in the time of crisis

Giovanni and Claudio are fond of stressing that the mafia are the only or one of the main influences in their work. Yet, in the same vein, Claudio has illustrated Per questo mi chiamo Giovanni ('That's why I'm called Giovanni’, Fabbri, 2004). It's a comic book based on a children's book by Luigi Garlando, in which a father explains who the mafia-killed magistrate Giovanni Falcone was to his son. ‘But now we are focused on the John Doe series, an on carrying out the orders of screenwriters!’ he jokes. ‘I take inspiration from anything,’ says Giovanni for his part, who also works for Bonelli comics in sampling the Italian horror comics series Dylan Dog and Dampyr. Both certainly have a strange job, which Claudio has been doing for a long time, having started off with a diploma in fine arts in Palermo. Giovanni arrived at his job definitively, after having studied international development and with a doctorate - in chemistry!

Giovanni and Claudio are fond of stressing that the mafia are the only or one of the main influences in their work. Yet, in the same vein, Claudio has illustrated Per questo mi chiamo Giovanni ('That's why I'm called Giovanni’, Fabbri, 2004). It's a comic book based on a children's book by Luigi Garlando, in which a father explains who the mafia-killed magistrate Giovanni Falcone was to his son. ‘But now we are focused on the John Doe series, an on carrying out the orders of screenwriters!’ he jokes. ‘I take inspiration from anything,’ says Giovanni for his part, who also works for Bonelli comics in sampling the Italian horror comics series Dylan Dog and Dampyr. Both certainly have a strange job, which Claudio has been doing for a long time, having started off with a diploma in fine arts in Palermo. Giovanni arrived at his job definitively, after having studied international development and with a doctorate - in chemistry!

Crisis is good for comics

But how is the comic book viewed in Europe, and what role can it have in a crisis? ‘In (the Great Depression of) 1929, comics were in full swing,’ says Claudio. ‘In times of crises people liberate themselves from everything, except distraction.’ ‘Yes, but that is if there is a balanced relationship between entertainment and price,’ Giovanni specifies. ‘The problem is that the graphic novel is too expensive for only fifty pages of entertainment.’ Could it be that the potential of comics is not really being achieved? ‘In France, comics are an art form,’ says Giovanni. ‘A screenwriter has the same dignity as an author, a comic is on the same par as a book.’ In a careers guidance programme for young people, medicine, law, journalism and comic strip writing are all offered as options. In Italy, it is seen purely as a means of entertainment, with an obsession for legibility and little serious criticism (with the exception of Italian writer Umberto Eco), whilst in Spain it is experiencing a certain rebirth, even if the market is scarce.

It has been years since Giovanni left Palermo. ‘Barcelona reconciles the best of northern and southern Italy. There is work, bureaucracy and hospitals function, but the city is perfectly human, the food resembles our own and there is human warmth - the latter mostly thanks to the immigrants!’ Even Claudio is leaving his job at the Scuola del Fumetto ('Sicilian School of Cartooning') in Palermo: ‘Ever since I was an Erasmus student in Valencia, I have wanted to live in Spain. Now, yes, I am going there because I can no longer bear the way you are treated in Sicily. I can no longer bear being one of (prime minister Silvio) Berlusconi’s toy things; do you think that in the last government elections - between somebody practically condemned as the mafia and a symbol of the fight against the mafia (Raffaele Lombardo and Rita Borsellino - ed), the former really won by 60%?’ Emigrating is no longer painless. ‘Even if it is not our principal commitment,’ Giovanni replies, ‘above all, we will write comics.'

Translated from Brancaccio: la mafia in un fumetto