Citizen Science and Sensitive Subjects: The Case of Mass Tourism

Published on

Translation by:

Eleanor Cooke

Eleanor Cooke

There is a common stereotype that researchers, including those working in social sciences, struggle to come down from their ivory tower. People often believe that scientists have difficulty opening up to society, never looking beyond their research. This, however, is clearly not the case. All over Europe, researchers and organisations work together on tangible projects, which sometimes cover socially sensitive topics. In this last instalment in the “Common Ground” series, we’re taking a stroll through Lisbon.

Lisbon. With the Tower of Belém, pastries, and trams rushing along steep winding streets, the city is the ideal destination for those wanting to step away from the humdrum rat race of everyday life.

The Portuguese capital is certainly very popular. In 2021, 2 million tourists spent at least one night in the city or its inner suburbs. This is a sizeable figure for a region populated by around 2.8 million inhabitants (with 500,000 living in Lisbon*).

Lisbon is not only in vogue with tourists travelling with the new ‘EasyJet, AirBnB and Instagram’ triad.

For the past 10 years, various government incentives have also increased the number of “digital nomads” (a trend previously covered here) and of European pensioners spending a few months of the year in Portugal. There are 700,000 expats in Portugal, according to official statistics.

.

These new groups of visitors are having a definite impact on the city: rising rents, higher prices in small retail outlets and food businesses, forced gentrification in certain areas, etc. As in every city, many inhabitants fear that their neighbourhood will be emptied of their heart and soul, and that, sooner or later, they will be forced to leave.

The case of San Antonio

This is a complex, politically sensitive topic not only at local level, but also at a European, or even international level. Mass tourism has radically changed a great number of European cities over the past decade.

But how can this impact be studied? One of the methods used to assess the impact of mass tourism is to zoom in on a specific area, in order to study all the social interactions stemming from the arrival of these new groups of people. This method was used in the COESO pilot project, which led researchers from the Centre for Research in Anthropology CRIA to work alongside the environmental NGO ZERO in the San Antonio district of Lisbon.

Together, the organisations worked on the impact of developing tourism and how it is changing the way that Lisbon’s urban space is used on an everyday basis. This project, designed before the Covid-19 pandemic, found the San Antonio district, located right in the heart of the Portuguese capital, to be an obvious choice for study.

While this area has indeed undergone changes brought on by tourism, its residents still feel a strong sense of belonging to the neighbourhood and some streets and alleys still have a large working-class population.

Over several months, researchers and activists from the NGO worked together on the ground. They first gathered the neighbourhood’s official documents, as well as maps and photos that would show the changes occurring in San Antonio. All of this work can be explored on their blog, which is full of archived newspaper articles and other documents.

Researchers and activists decided together on how to prepare for interviews with different members of the community (residents, business owners, local elected representatives and officials) and how to run focus groups.

This gave people the opportunity to share their impressions during long discussions, which in some cases lasted over two hours. This allowed researchers to fully grasp the locals’ interactions with their neighbourhood, whether they were long-term residents or new arrivals. For instance, these discussions showed that, to many residents, being a tourist was synonymous with being foreign, first and foremost.

“Whether they are people visiting for a few days, digital nomads or pensioners that have lived there for years, these groups are all classed as tourists by their neighbours,” explains historian Elisa Lopes da Silva, who is deeply committed to the project.

ZERO and the CRIA also worked together to share their research activities with the public by organising exhibitions and other public events.

Local dilemmas

Interestingly, this research was carried out right in the middle of the pandemic. From one day to the next, borders closed and streets emptied, as the city’s residents found themselves in lockdown. Our relationship with urban space and community living changed overnight.

This radical change meant that the pilot project became even more relevant. As well as studying the new relationship that residents and the wider local community had with a district changing before their eyes, the project also took on a new dimension, as the relationship between social science researchers and activists took a different direction.

On one hand, the research team tried to make their scientific process as neutral and unbiased as possible. They needed to express the subtleties they observed at local level. Residents living in the district’s apartments may indeed have a negative view of mass tourism, but the business owners, often operating on the ground floor of the very same buildings, are usually more favourably disposed to this new clientele.

Local elected representatives are also faced with conflicting interests. Elected representatives of a local area, who do not get a single cent of the tourist tax charged by the city's hotels, aim to preserve their neighbourhood and protect access to affordable housing. However, the municipalities that do receive this tourist tax need this type of income to fund schools and public services.

On the other hand, as Elisa Lopes da Silva explains, “an NGO [non-governmental organisation] has a political relationship with a place”. For ZERO, the COESO project also became a tool in reshaping their advocacy campaigns and strategies at a local, national and even European level.

Drawing on citizen science in every phase of the scientific process

These different goals meant that it was sometimes difficult for members of the project to agree on what questions to ask or on how to interpret results. “Our discussions were very stimulating, and were sometimes difficult,” explains Elisa Lopes da Silva.

While the two parties managed to find common ground when it came to interpreting results, they still came to different conclusions. “This experimental challenge was the whole point of the project,” continues the historian.

“Citizen science needs time to work its magic,” explains Susana Fonseca from the NGO ZERO. Fonseca also adds that sometimes it is necessary to register a disagreement rather than being “paralysed” by the need to reach a consensus at all costs.

Having said that, the experiment was a success. “We are now more open to working with other partners” says Elisa Lopes da Silva. “The exploratory and experimental parts of citizen science projects are very interesting,” she adds. “It’s a good way to question our scientific approach when we go into the field,” she concludes.

Looking ahead to future projects, the historian states that she will pay more attention to developing a relationship with participants as early on in the process as possible. Citizen science is not only about deciding how to present the results of a scientific study. It can also develop and enhance a study by involving people other than researchers.

Visualising change

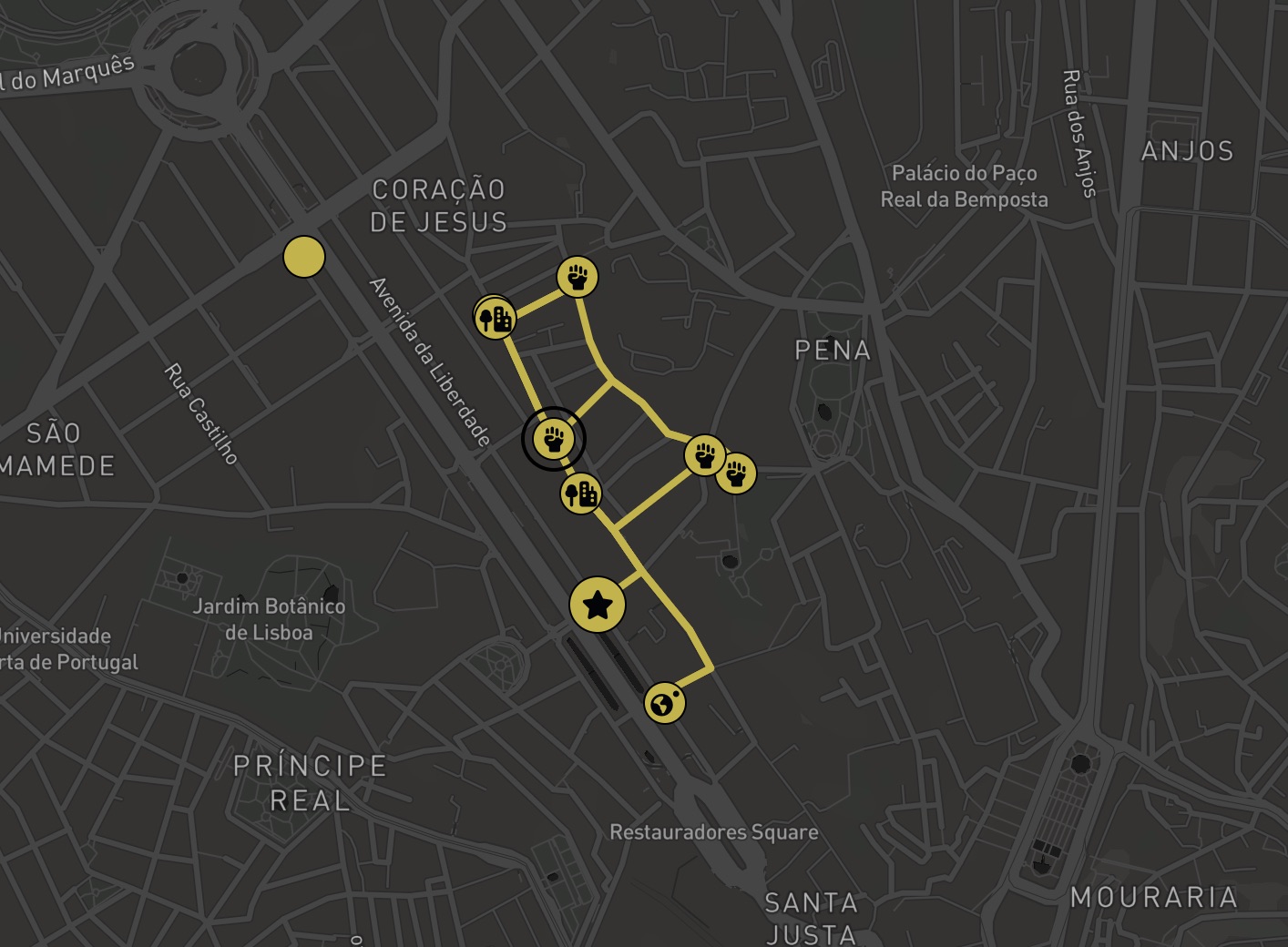

How can these results be shared with the general public? Through many different channels. For example, to visualise and understand the changes taking place within a neighbourhood, it is not only important to spend time on the streets but also to get a bird's-eye view of the district.

Using the website Sao José, a Transmedia Ethnography of Tourism in Lisbon, new itineraries were created showing the changes taking place in San Antonio, made available to everyone.

What about the impact of mass tourism on other European cities? This project can, without a doubt, provide answers to local problems regarding the use of public goods in Lisbon, but it can also be relevant to other European cities facing the same transitional issues.

“Transitions are always challenging. The more inclusive we are in preparing for them and working towards them, the more durable, enjoyable and sustainable they can be,” Susana Fonseca explains philosophically.

“What would I recommend for residents of Bruges or other cities that are popular with tourists?” says Elisa Lopes da Silva. “Create a platform for residents and other members of the local community to meet. Naturally, people who are only staying in the city for a few days should not have the right to participate.”

She then adds, “Having said that, it does seem that only the people who have lived in a city for a long time have political representation. It’s also important to guarantee everyone a certain freedom of movement.”

—

This project was organised in collaboration with the COESO research project (Collaborative Engagement on Societal Issues), combining social sciences and participatory research. Coordinated by the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, or School of Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences, COESO is funded by the research programme Horizon 2020. The content of this article may not under any circumstances be considered as reflecting the position of the European Commission, which may not be held responsible for the information it contains.

Cover photo: Urban Decay, Lisbon 2010 by Pedro Szekely

Translated from Science citoyenne et sujets sensibles: l’exemple du tourisme de masse