China, superstition and sport – from monastery to NBA

Published on

In this giant Asian country, even sport needs a less bureaucratic and more open model in order to be more competitive

As we see in Chinese ‘Wuxiapian’ films (a Chinese epic cinema genre), demonstrating physical skill is a fundamental aspect of Chinese culture. The body is a medium of expression for a whole world, with its logic, its need for unity and regulation. It’s perhaps inevitable, therefore, that we should reflect on sport and physical activities in China in 2008, year of the Olympics.

The Chinese way to counter-spells

Many commentators have said that the date chosen is no coincidence: : competition begins on the 8th August 2008 at 8pm (8/8/8/8). This is in fact the lucky number which represents the snake, the infinite cycle in the kundalini (a philosophy that began in India and that later spread to China). The first signs of superstition are surfacing on many blogs and popular information sites: the conflicts in Tibet took place on 14 March (1 + 4 + 3 = 8), the earthquake in Sichuan on 12 May (1 + 2 + 5, same result). Sorcery and rites apart, China is preparing itself to make the very most of this great event. Sport has been a central aspect in the culture of this Asian country for at least 4, 000 years. Since the time of the Zhou Dynasty (1066 -771 BC) up until today, archaic forms of culture have replaced each other, including archery, jiaodi (a form of free fighting) and jujitsu, polo and football.

Many commentators have said that the date chosen is no coincidence: : competition begins on the 8th August 2008 at 8pm (8/8/8/8). This is in fact the lucky number which represents the snake, the infinite cycle in the kundalini (a philosophy that began in India and that later spread to China). The first signs of superstition are surfacing on many blogs and popular information sites: the conflicts in Tibet took place on 14 March (1 + 4 + 3 = 8), the earthquake in Sichuan on 12 May (1 + 2 + 5, same result). Sorcery and rites apart, China is preparing itself to make the very most of this great event. Sport has been a central aspect in the culture of this Asian country for at least 4, 000 years. Since the time of the Zhou Dynasty (1066 -771 BC) up until today, archaic forms of culture have replaced each other, including archery, jiaodi (a form of free fighting) and jujitsu, polo and football.

Sport and the community

This is a history bound to a completely different perception of sport: for western culture going back as far as Athens, it’s a simple exultation of the physical. For eastern, oriental culture, a means of contemplating humanity in its union with the cosmos. Afterwards, in Communist China, the religious/philosophical substrate became political ethics: the individual does not stand out by themselves, but rather as an integral part of the entire community – a particle that exalts the whole. From 1995, the government has promoted a national programme to spread the practice of physical activities: there are 620 000 institutions including gymnasiums, stadiums and swimming pools. Life expectancy has increased by 3.25 years. There is a growth in sports which until recently were little practised, such as bungee jumping, horse riding, bowling, skateboarding, female boxing and tae-kwondo.

This is a history bound to a completely different perception of sport: for western culture going back as far as Athens, it’s a simple exultation of the physical. For eastern, oriental culture, a means of contemplating humanity in its union with the cosmos. Afterwards, in Communist China, the religious/philosophical substrate became political ethics: the individual does not stand out by themselves, but rather as an integral part of the entire community – a particle that exalts the whole. From 1995, the government has promoted a national programme to spread the practice of physical activities: there are 620 000 institutions including gymnasiums, stadiums and swimming pools. Life expectancy has increased by 3.25 years. There is a growth in sports which until recently were little practised, such as bungee jumping, horse riding, bowling, skateboarding, female boxing and tae-kwondo.

For Maggie Rauch, director of the American website China Sports Today, there has always been an enormous interest in sport in this country, and at most, ‘the Olympic games have just increased the tendency.’ Alongside the traditional schools of table tennis (the Chinese Deng Yaping remains the greatest player of all time), tajiquan (also known as shadow boxing), xiangqui (the Chinese version of chess), weiqi (a board game with round tokens, ancient Go) and badminton, more are joining the avant-guarde for disciplines traditionally regarded as European or American.

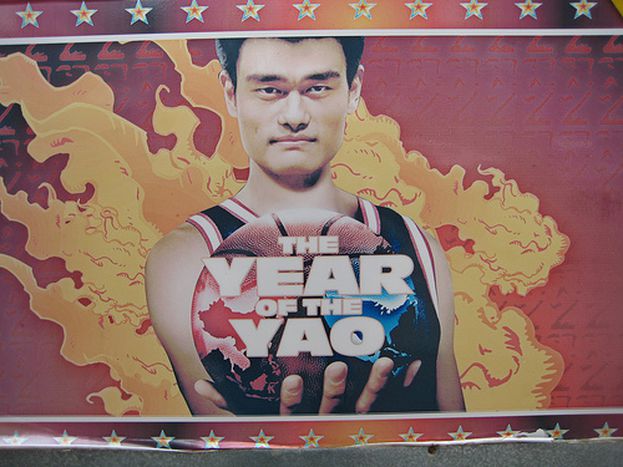

The Chinese in the NBA

ince 1994, starting with football, state investment has been replaced by that of the private sector. Commercial television stations buy the broadcasting rights for large events, and the professional sporting level is developing. Yao Ming is the first basketball player to arrive in the NBA from China, rousing the passions of millions of young people, children of the generation held spellbound by the spectacular Maike Qiaodan, aka Michael Jordan.

Football is looking to legitimise itself internationally by making use of experienced foreign experts (the home team bench is now entrusted to the Serb Vladimir Petrović), rugby is growing in popularity day by day, to the point where it has become the official sport of the army (Zhang Zhiqang is the first Asian to play in an English team, for Leicester Tigers), the exploits of the tennis player Zheng Jie in the last Wimbledon tournament have attracted many girls to tennis; Ding Junhui is one of the ten best snooker players in the world, making the ‘stick’ a favourite amongst the young. Baseball and golf are blackballed, the latter even disqualified by the government, who see a waste of funds and public land in the green fields. Bouquets instead to swimming and diving, in which champions Guo Jingjing e Tian Liang have become the focus and stars for international advertising campaigns.

Progressive commercialisation brings the People’s Republic ever closer to the western liberal capitalist model. Maggie Rauch states that, ‘Chinese sport is following the changes in the economic model of this country, moving closer to the market model. A rigid and bureaucratic model would prevent teams from being competitive. China has ‘realised that to be successful, it has to adopt a more open model even within sport.’ What does she foresee for the Olympic results? ‘I couldn’t say from discipline to discipline, but I would bet a few renminbi (RMB, the Chinese currency) that China will step up to the podium on quite a few occasions, and that they will even award themselves many gold medals.'

Progressive commercialisation brings the People’s Republic ever closer to the western liberal capitalist model. Maggie Rauch states that, ‘Chinese sport is following the changes in the economic model of this country, moving closer to the market model. A rigid and bureaucratic model would prevent teams from being competitive. China has ‘realised that to be successful, it has to adopt a more open model even within sport.’ What does she foresee for the Olympic results? ‘I couldn’t say from discipline to discipline, but I would bet a few renminbi (RMB, the Chinese currency) that China will step up to the podium on quite a few occasions, and that they will even award themselves many gold medals.'

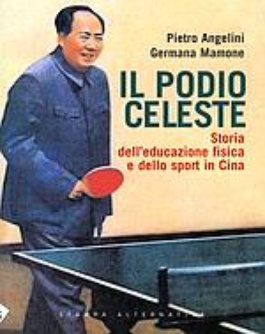

For those keen to know more, a book has just been published in Italian entitled Il podio celeste, storia dell'educazione civica e dello sport in Cina (‘The celestial podium, a history of civic education and sport in China, Stampa Alternativa, 2008). The book, by Pietro Angelini and Germana Mamone, investigates the spread of sport in this enormous country.

Translated from Lo sport in Cina: l’uomo e il cosmo in relazione