Chelas: not such a dodgy neighbourhood of Lisbon

Published on

‘You were in Chelas? I’ve lived in Lisbon for eight years and I have never risked going there,’ says Melinda, a 23-year old student who moved to Portugal with her family from Cape Verde. Melinda isn’t the only one who knows of the bad reputation of this district

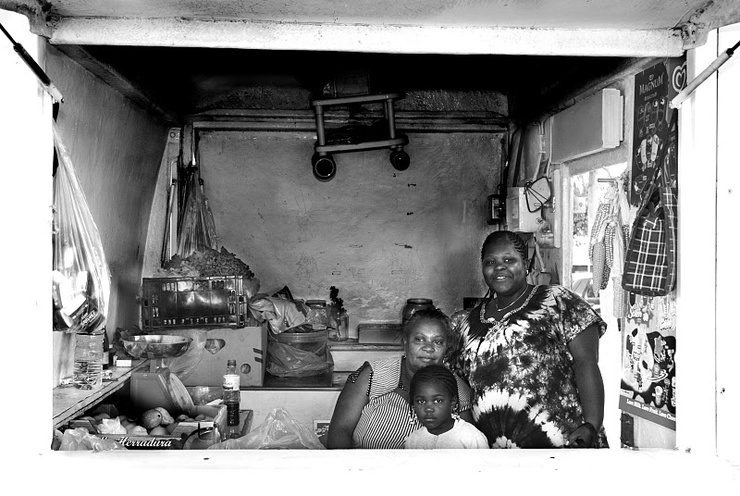

Cape Verde, Guinea, Sao Tome, Zanzibar, Angola, Mozambique… Portugal made a lot of mistakes in the past, ravaging the resources of some African nations, and now has a moral debt to pay. Because they usually speak Portuguese and national immigration policy is friendly for them, lots of Africans move to the country of their former coloniser in the hope of a better life. In general Portuguese society is friendly to these talkative Africans. ‘There is no racism here, especially amongst young children,’ says Mais, a 40-year-old woman carrying her small daughter Camille and sitting opposite her old mother Adelaide. The three generations of women are sitting in a tiny kiosk where Adelaide sells fruit and vegetables on the street. Their family moved to Portugal from Cape Verde three decades ago and now live on the edge of poverty, earning what little money they can from selling goods to other Chelas inhabitants. But they do not complain about their life here. ‘At least Camille can study in school with other children and we feel safe here,’ says Mais in French.

After leaving the metro at Chelas station, the first impression is that it is ordinary: normal streets, standard Portuguese buildings, smily people and the usual car congestion. ‘It is not safe down here, especially after 7 o’clock, so better not to search for troubles cause you can find them,’ warns Jorge Barbosa, an officer from a police station not far from the metro’s entrance. ‘You can lose your camera easily, so better keep it hidden.’ We turn to head south. ‘Don’t go there!’ he shouts behind us. ‘It’s not a good place to hang around,’ agrees our bus driver before disappearing noisily in the smell of exhaust fumes, leaving us in the very heart of African part of this city. Now the buildings look a bit different; they are grey, overwhelming, neglected. Inhabitants look like they are loitering. Those we find who speak French or English are not interested in being interviewed. ‘I moved here with my family from Guinea twenty years ago,’ says Nelson, a 64-year old man standing in front of local food shop and speaking in French. ‘I never think about how our life here looks like. We simply live from day to another, trying to avoid problems and bring up our grandchildren as good people.’ In this sleepy, almost dull neighborhood there is only one eye-catching building, whose purple, yellow, pink, green and blue-colored walls are so shockingly different from the surroundings that we are drawn to it, like a moth to a bulb. A narrow corridor leads inside; the calm atmosphere of this district muffles our instinct of danger, so we leave the street to explore what is behind the wall.

It feels like entering a different dimension. The courtyard is empty but oppressively stuffy, with a muffled hip-hop beat from some open window piercing the silence. Click! We take one picture and chaos descends. Immediately, more than a dozen young black people appear from different sides of the courtyard, hiding their faces in t-shirts, running towards us and yelling in Portuguese, encircling us and started pushing, trying to take our cameras, screaming that we are undercover police. We see wild anger in their bloodshot eyes. When they realise that we’re foreigners, some of them start yelling in English. Fighting to keep our cameras in our hands, we persuade them that we are just lost in their neighborhood while visiting Chelas to see how people are living here. Finally, they are convinced, as they stand and watch all the pictures be deleted from the memory card.

As we leave the building, their curiosity gives us the initiative. Shaking their hands, we gain a bit of trust and start asking about their life, roots and problems. Showing respect, we somehow manage to start a discussion.‘You took a picture of two guys making a deal with drugs,’ says Dave, a young Briton here to visit his family living in Chelas. ‘This is a site where they sell this stuff for the whole district.’ As for the station directly opposite the building, Dave answers that we will never see a policeman here. ‘They don’t come inside, they are too afraid of us.’ There are a few young white Portuguese boys among the mainly black group. ‘We’re brothers and sisters, skin colour doesn’t matter,’ they say. ‘They live on the same street, go to the same schools and deal with the same problems, so why hate each other?’ adds Dave.

All around children talk and play without fear. 14-year old Melissa, Neuza and Ugu say Chelas is their home. They don’t care about the origins of their parents or skin colour. ‘If you are from here, you don’t have to be afraid of anything,’ says Melissa. ‘Just accept and respect others.’ The last word goes to the street name that the shop, school, kindergarten, police station, dealers nest and vegetable kiosk are on both sides of: Avenida Joao Paulo II, or Avenue John Paul II.

This article was first published on the blog Europeinmotion

All images: © An-Sofie Kesteleyn