Catalonia And Scotland: Two very different struggles for independence

Published on

Translation by:

Jaume BarberScotland has been granted the right to fight a democratic referendum. Catalonia, on the other hand, is ever rebuffed by an intransigent Spanish government. Tensions are rising and support for the Catalan independence movement is growing quickly

In September 2014, 5 million Scots will be asked to decide, ‘Should Scotland be an independent country?’ A small question of immense magnitude, it will determine Scotland’s future. With less than a year to go before the historic plebiscite, opinion polls are so far inconclusive. The measured campaigns being led by both sides make for a meaningful and rational debate. This is the height of democracy.

Over on mainland Europe, the controversial triangle that is Catalonia saw 1.5 million citizens link hands on 11 September, forming a 250 mile human chain in support of Catalonian independence. However, perennial calls for independence aside, Scotland and Catalonia have little in common.

A NATION OF NATIONS OR A SINGULAR NATION?

The persistent refusal of the Spanish state to recognise Catalan independence has brought Catalonia to the end of its tether. In 1989 the Catalan population was inspired by Baltic independence. Now they are weary. Since the 1707 Act of Union, the United Kingdom has defined itself as a collection of nations. Spain, on the other hand, has never acknowledged the plurality of its subjects, instead adhering to a centralised state with a Castilian foundation. The singularity of this model refuses to accept the diversity of its makeup. Just look at a map of Spanish roads and railways. Madrid is the undisputed focal point.

In 1714 the French Bourbon dynasty won the War of Spanish Succession. Prince Philip V of Spain defeated the Catalan armies, becoming undisputed king of Spain and asserting Castile as the dominant force in the region. Before the Bourbon victory ‘Spain’ had been nothing but a geographical term, much like pre-unification Italy. However, after 1714, the diverse region was united under the Castilian banner and the terms ‘Castile’ and ‘Spain’ were henceforth considered synonyms. Catalonians mourn the defeat of 1714 as the end their autonomy.

In 1714 the French Bourbon dynasty won the War of Spanish Succession. Prince Philip V of Spain defeated the Catalan armies, becoming undisputed king of Spain and asserting Castile as the dominant force in the region. Before the Bourbon victory ‘Spain’ had been nothing but a geographical term, much like pre-unification Italy. However, after 1714, the diverse region was united under the Castilian banner and the terms ‘Castile’ and ‘Spain’ were henceforth considered synonyms. Catalonians mourn the defeat of 1714 as the end their autonomy.

Although Castile was politically dominant, Catalonia has always been and still remains the economic driving force in Spain thanks to the industrial revolution. England could exist without the Scottish economy, but Spain has come to rely too heavily on the economy of Catalonia. Catalonia accounts for 20% of Spain’s GDP with an economy the size of Portugal’s.

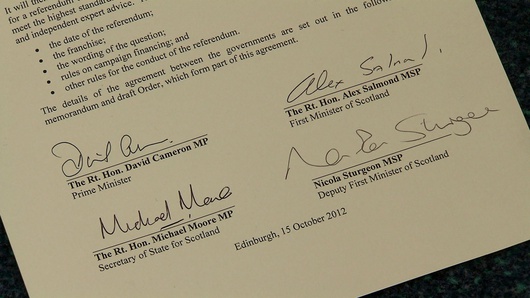

Although the UK is campaigning democratically against Scottish independence, the British government has embraced the idea of a referendum. On the other hand the Spanish government flatly dismisses Catalan aspirations and ignores the growing number of secessionist supporters. By dogmatically rejecting the idea of independence, the Spanish government is denying itself the opportunity to mount a ‘no campaign’. The government thus provides further ammunition for the secessionists and nudges undecided citizens into their arms.

CHAOS AT HOME BREWS TROUBLE ABROAD

The economic and political crisis has eroded the integrity of Spanish state institutions. This weakness is manifest on the international stage. The right-wing government seeks to conceal its insecurity by escalating nationalist rhetoric. A diplomatic crisis erupted between Spain and the UK in August when the Spanish government imposed contentious border checks on vehicles entering the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar. The British prime minister David Cameron called his Spanish counterpart Mariano Rajoy twice to spell out his ‘serious concerns’ regarding Gibraltar. In June 2013, Cameron allegedly criticised Rajoy’s handling of Catalan demands for independence at the G8 summit in Northern Ireland.

Separatist sentiment is reaching fever pitch. Support for independence in Catalonia has doubled to 50% over the last two years. The government is pouring fuel on the fire by passing centralising laws, such as the controversial Wert Law which will come into effect in 2014-15. Cuts to the already scanty Catalan budget have further infuriated people in the region. The Catalan people feel they are being asked to bear a disproportionate economic burden. The Spanish government asked Catalonia to reduce its deficit to 1.5% in 2012, whereas Spain as a whole had a target of 6.3%.

In September 2012, prime minister Rajoy rejected budget proposals put forward by the Catalan leader Artur Mas which would give Catalonia the right to raise and spend its own taxes. The resultant demonstration with the slogan ‘Catalonia: a new European state’ was attended by one and a half million people.

In December 2012 Mas was re-elected as regional leader. His centre-right Convergence and Union (CiU) alliance formed a coalition with the centre-left Republic Left (ERC) party. The coalition is united by their desire for a referendum on secession in 2014.

The rupture between the societies of Spain and Catalonia is growing day by day. This leaves politicians with little room to manoeuvre. Spanish politicians from the left and the right are trapped in a constitutional quagmire. They discuss democracy, but undemocratically exclude others from the debate. On the other hand, Catalonian society is clearly focused on one thing - pushing its government to fix a referendum date before the end of 2013.

Translated from Catalunya y Escocia: dos actitudes frente a un mismo anhelo