Canvas, Otpor, Pora: Serbia's brand is non-violent revolution

Published on

Israa Abdel Fattah, Mohamed Adel and Asmaa Mahfouz will be remembered as the ones who largely contributed to dismantling Hosni Mubarak's 30 year rule over Egypt, and one of them revealed this year that he trained with similar youth organisations in Belgrade

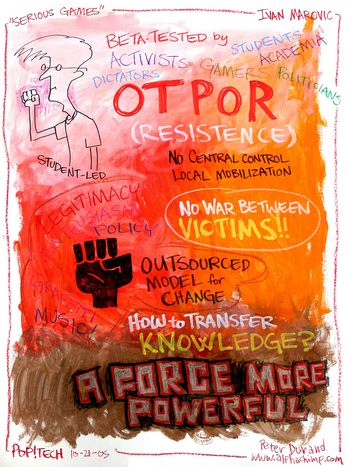

'The journey from dictatorship to democracy does not solely consist of overthrowing non-democratic leadership or organising fair and free elections. It is foremost a longterm institution building process,' says Srdja Popovic, director of the centre for applied non-violent actions and strategies (Canvas) in Belgrade. Recently Canvas received massive media attention because one of the leaders of the April 6 Egyptian youth movement Mohammed Adel stated that it was in this particular centre where they received advice on how to organise protests in their country.

The 38-year-old was himself one of the co-founders and leaders of Otpor! ('Resistance'), a Serbian youth movement that played a significant role in the downfall of former Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic’s regime in the country eleven years ago. Since then, he has been advocating for citizen activism throughout the world; Serbia has a new brand on its plate, and it's called non-violent revolution. ‘The media have a way of making a mountain out of a molehill,' he says. 'They’ve turned a story of several brave Egyptian activists who came to a human rights workshop in Serbia into a romantic tale of importing and exporting revolution,' His organisation has set up workshops for over 1, 000 people from 37 countries.

Romantic notion of revolution

Non-violence movement strategies have been known for decades and are taught at some prestigious universities. However, the idea of a non-violent protest as a Serbian brand was portrayed in the Serbian media couple of years ago after the orange revolution in Ukraine. It was then reported that Otpor activists met with members of

Non-violence movement strategies have been known for decades and are taught at some prestigious universities. However, the idea of a non-violent protest as a Serbian brand was portrayed in the Serbian media couple of years ago after the orange revolution in Ukraine. It was then reported that Otpor activists met with members of

Pora (‘

'), a Ukranian youth movement that was one of the organisers of their own revolution. Similar meetings were also held with activists from

Georgia, Zimbabwe, Burma

and the

Maldives

. Add to that an

MTV Free Your Mind award

that Otpor received in

2000, and you get a perfectly sellable brand.

The media potentially gave a romantic notion to the whole story, but the fact that the documentary of Otpor’s doings Bringing Down a Dictator (2002) was seen by 23 million people vouches for the spreading of their ideas.

And what’s there not to be romantic about? After all, the fist symbol of Otpor, was reportedly a product of a man in love; Nenad Duda Petrovic, now 37, was asked to create a logo for some student organisation by a girl who he was in love with. It took him only two hours to draw a fist that would later on represent the resistance of people toward dictators’ regime. That symbol has since been seen on protests in Georgia, Venezuela and recently in Egypt.

And what’s there not to be romantic about? After all, the fist symbol of Otpor, was reportedly a product of a man in love; Nenad Duda Petrovic, now 37, was asked to create a logo for some student organisation by a girl who he was in love with. It took him only two hours to draw a fist that would later on represent the resistance of people toward dictators’ regime. That symbol has since been seen on protests in Georgia, Venezuela and recently in Egypt.

Petar Milicevic was one of the trainers at workshop that CANVAS organised for Egyptian activists in 2009. In his opinion, the methods that were presented at the training were perfectly applied during the Egyptian revolution. 'Not a single change of power was successfuly done because of some international training and support,' notes Milicevic. 'The desire for social and political changes has to come from people. Everything else is more appealing than spending eighteen days in Tahrir Square while surrounded by (former president Hosni) Mubarak’s forces. The key to Egyptian success was that the revolution leaders recognised the needs of their society.'

Happily-ever-after or not?

However fascinating the story of Egyptian uprise seems, the fight didn’t end on the day Mubarak resigned on 11 February. While global attention has now turned towards Libya, Bahrain, Syria and other countries in similar political situations, it is up to the Egyptian people to start rebuilding their political institutions. 'The next important step is changing the grotesque constitution that is long past its expiry date. After that there's the registration of political parties, freedom of speech and assembly, autonomy of educational institutions and separation of legislative, executive and judicial power…'There’s a long road ahead of them, but they don’t lack hope and enthusiasm,' says Srdja Popovic.

'People think that a better life comes right away. It doesn’t'

High hopes can also take a toll in the process. A decade after Milosevic’s downfall, Serbians are feeling disappointed by the outcomes of their revolution. The general apathy is deepened by poverty, high corruption rate and a lack of trust in politicians and institutions. Recent research in Ukraine showed similar results. 'Serbia definitely looks better ten years after Milosevic than it did during the nineties. I can’t possibly think of anything from that period that we could be nostalgic about. The problem is that people think that a better life comes right away. It doesn’t, and then that enormous energy hits a brick wall when it has to deal with everyday issues. I hope Egypt will find a way to overcome that,' says Petar Milicevic. Judging by numbers, Egyptian people have passed their first democratic test by making a large turnout protest on 18 March to a popular vote on constitution changes. The story continues in August when the presidential elections will be held.

Images: main Pop!Tech art, Otpor! 2005 (cc) Peter Durand/ Alphachimp Studio/ alphachimp.com/ on Flickr/ videos: MTV award and trailer for movie (cc) technodrombg and (cc) AFMPF Films/Youtube